I’ve Seen the Future and I’m Not Going: The Art

I’ve Seen the Future and I’m Not Going: The Art

Scene and Downtown New York in the 1980s

by Peter McGough

Pantheon. 289 pages, $29.95

AT THE HEIGHT of their fame, Gary Indiana called David McDermott and Peter McGough the “Tupperware Gilbert and George.” Like so many comparisons, it is more clever than it is useful. But the two couples have similarities. Like Gilbert & George, an artistic duo known for their graphic art and performance, McDermott and McGough are gay men who sign their work together. They are a couple, although they now lead more separate lives. And like Gilbert & George, McDermott and McGough have made homosexuality one of their major topics, culminating in their Oscar Wilde Temple, an installation that incorporated many of their paintings.

But while Gilbert & George have created an image of anonymity that meshes with the glossy impersonality of their billboards, McDermott and McGough are everywhere in their rather homespun art, which is an outgrowth of the unusual way they live. “Tupperware” suggests the very American, domestic spirit of their work. Peter McGough’s memoir I’ve Seen the Future and I’m Not Going captures the silly, desperate decade they lived through and the peculiar ménage which is their major work of art.

David McDermott is the older of the two by a half-dozen years, but by the time Peter McGough moved to New York at nineteen to study (briefly) at the Fashion Institute of Technology, McDermott was already the master-of-ceremonies of the “New Wave Vaudeville” on 14th Street. The second time McGough saw him, McDermott opened the show with a “King Tut number … carried by scantily dressed slave boys.” The lyrics of the song included the lines: “Being a god could go straight to my head. … Just look me up in The Book of the Dead.”

Not only did McDermott have a place in the avant-garde circles of New York cultural life, he also had a philosophy. “Can’t you see,” he told the impressionable Peter, “all time exists at the same time. There are parallel universes out there in other galaxies. …. There are other Planet Earths out there. One is in 1928. Then another Planet Earth is in 1748.” Though several people already warned Peter that David was crazy, his teenage heart was aflutter. “There is no question,” Peter later admitted, “I was a bit mesmerized by McD.”

Peter, who wanted to have an “interesting life” in contrast to the suburban Catholic household he was raised in, put up with David’s “volatility and crazy theories.” He soon learned that disagreeing with David “meant overturned tables and smashed mirrors, among other things.” There’s no way to get around the simple fact that McDermott was nuts, and even a mesmerized naïve teenager had to see it. The strange part of this story is that their moments of peace and mutual satisfaction came when they painted together. They each thought the other’s painting was perfect.

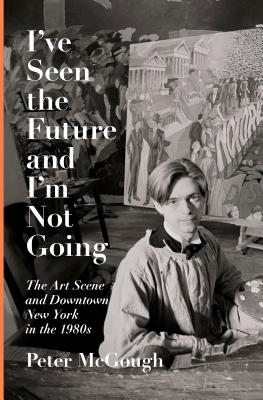

While the book is filled with images of David McDermott, there are relatively few of Peter McGough (except for the cover). Still, I never got a clear picture of McDermott. He has wiry red hair, but the features never quite come together. When they first met, Peter “couldn’t tell his age. He seemed part child, part old man. His comic face was somewhere between fourteen and forty.” McGough, however, always looks the same—he has a sweet, gentle, slightly aristocratic face and large deer-in-the-headlight eyes.

McDermott and McGough signed their work with two dates: the year in which the work was produced, and the year that the work embodies. David and Peter became famous not only for dressing in the clothes of the 1930s or the1890s, but also for trying to live in the past. They had no electricity, first because they couldn’t afford it but later because they preferred to live by candlelight. They removed the radiators and used the fireplaces for warmth and for cooking. They had no refrigerator but found a 1900 icebox that constantly had to be drained. But their refusal to accept modernity had creative results. They took up photography, but they would only work with antique cameras and use the chemicals available at the time the camera was made. The results are haunting in a way that their paintings, with their chromolithographic colors, are not. This need to live in the past was much stronger for David, but Peter clearly enabled, encouraged, and sometimes enjoyed this way of life.

Living without modern appliances was a necessity for many years when they were homeless and starving, relying on a friend’s sofa for sleep and another friend’s coffee, toast, and eggs. They added to their limited diets by partaking of the refreshments at church and AA meetings. But when their work began to sell, living in the past became very expensive. They needed people to take care of their horses and buggies as well as their antique roadsters. They needed servants to wash the clothes in a bucket or cook on a woodstove. Peter writes that on a single day in the mid-1980s, they sold over $100,000 worth of art. But the money was gone three days later.

Their lavishness would have eventually brought ruin, but it was hastened by a young man that Peter calls Bastian. When they met, Bastian was a junior in prep school. That summer he joined them in Europe. He became a fixture in their upstate New York home, demanded a horse of his own and then a house of his own. He destroyed the fragile intimacy between David and Peter. Worse still, he was straight, so beyond a bit of cuddling, they didn’t even get sex out of him. He might have been beautiful and intelligent, but he was endlessly destructive. He died in his thirties after falling off a horse.

Bastian stayed around while things were good. After the IRS struck, he was gone. Income tax was not around in the 1880s but it was in the1980s, and the IRS demanded that McDermott and McGough pay the fortune that they owed the government. Since they had no savings, they lost all three buildings they owned, all of the furnishings, and all of their art. The only good thing Peter got out of it was Bastian’s exit. Even Bastian couldn’t get blood from these turnips. The two ended up back on the street, where they began. McDermott moved to Ireland, leaving McGough to deal with the legal fallout. And just when you thought things couldn’t get worse, they did: McGough was diagnosed with AIDS.

For most of the book, McGough depicts himself as a person who loved to dress as a 1890s dandy, but is too afraid of McDermott’s rages to oppose David’s demands that they live without modern comforts and appliances. Yet it seems these delusions of living in the past are more deeply engrained than McGough wants us to believe. In any case, he insisted on treating AIDS with herbal and dietary remedies rather than with modern medicine. He survived only because of Jacqueline Schnabel, the wife of Julian Schnabel, who finally got her old friend the treatment he required.

McDermott and McGough are not, after all, a “Tupperware Gilbert and George.” They are much more frightening and more human than that. If anything, they are like the two Scottish painters Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde, known as the Two Roberts, who took British painting by storm in the 1940s and fell out of favor in the ’50s, dying of alcoholism in the ’60s. They, too, signed some works together, and their styles are so similar that the unsigned works get wrongly attributed. What brings the two couples together is not just the similar self-destructiveness of their personalities but that they were “acutely conscious,” to use Roger Bristow’s words, “of the need to generate a semi-mythical reputation in order to forge success.” It seems that queer couples do not just make art together; they must make a world together, a mythic bubble that ultimately bursts.

David Bergman, an English professor at Towson University, is the poetry editor of this magazine.