IN FULFILLMENT of his gauntlet-throwing declaration, in A Woman of No Importance, that “A man who can dominate a London dinner-table can dominate the world,” Oscar Wilde did just that—if by “world” we mean the view from the chic Hotel Café Royal where he held court, polishing his epigrams, sipping champagne, and gazing besottedly at his young lover Lord Alfred Douglas. If he were alive today, he’d conquer the Twitterverse, too, no doubt.

In a very real sense, he has: his epigrams and aperçus are everywhere on social media. A Google search for his name turns up 26 million hits. The bon mots that have made him the most-quoted English-language author after Shakespeare are as wildly popular now as they were in 1895, when An Ideal Husband and The Importance of Being Earnest were playing to sold-out houses in London’s West End. Wilde, like Shakespeare, combines deathless style with ageless insights—about morals and manners, culture and nature, artifice and authenticity, society and the individual, and, of course, love and sexuality.

Juxtaposed with the issues of our day, Wilde’s “phrases and philosophies” (as he called them) offer a bracingly fresh, and amusingly oblique, angle of attack on the moral crusades, social norms, identity politics, and ideological tribalism of the 21st century, while reminding us just how Victorian we still are—and just how prescient Wilde was. His wit, Wilde scholar Regenia Gagnier remarked to the BBC, is “extremely modern in that it breaks up the ideology, it breaks up the fixed ways of seeing.”

A quip like “There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about” (from The Picture of Dorian Gray) strikes a responsive chord at a moment when we weigh our social status in likes, shares, and retweets.A witty pronouncement like “It is personalities, not principles, that move the age” (Dorian, again) cuts a little closer to the bone in an America that elected a reality TV star as president. Certainly, Trump’s stunning transformation of the Republican party into a personality cult whose only real allegiance is to a dollar-store Mussolini makes Wilde sound as up-to-the-minute as any msnbc pundit. And his ruminations on the increasing mediation of firsthand experience by art and the mass media—“Life imitates art far more than art imitates life,” he writes in “The Decay of Lying”—beat postmodernism to the punch by a century. Nearly a century before the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard proclaimed the Death of the Real, rendered extinct by media simulations, Wilde characterized the 19th century as “largely an invention of Balzac.” Likewise London’s melodramatic fogs, a fixture of penny dreadfuls and Gothic novels, “did not exist till Art had invented them,” insisted Wilde, adding: “Sunsets are quite old fashioned. They belong to the time when Turner was the last note in art. To admire them is a distinct sign of provincialism of temperament.” (Also from“The Decay of Lying.”)

Wilde’s sayings are ubiquitous in the age of social media not only because he’s a man for our times but also because his epigrams, anecdotes, and slyly satirical zingers—debuted in conversation, perfected in his plays, and spread far and wide by the press—were the tweets of the 1890s, born to go viral. And go viral they did, partly because they conferred a borrowed brilliance on anyone who quoted them. Sos Eltis, author of Revising Wilde: Society and Subversion in the Plays of Oscar Wilde, points out in one of her Oxford lectures that reviews of his plays often ended with a “list of epigrams and paradoxes and witty sayings of the play as a kind of take-home goodie bag that you could use in parties yourself.”

Wilde foretold our celebrity culture and the invented persona of the Instagram influencer. As a 23-year-old Oxford undergraduate, he boasted: “Somehow or other I’ll be famous, and if not famous, I’ll be notorious.” Already, he was jotting epigrams in a notebook: “Life is a riddle, and we are always being asked to guess the answer at the wrong moment.” And, more scandalously: “Boys—like postage stamps you must lick them first if you want them to be of use.” These were dress rehearsals; his first smash hit was the one-liner picked up by the press and repeated by the smart set: “I find it harder and harder every day to live up to my blue china,” an arch remark that summed up in a sentence the Æsthetic Movement’s belief in the moral force of beauty while at the same time hitching a ride on the late-19th-century mania for Chinese pottery, Japanese prints, and all things “Oriental,” a craze whose devotees included Claude Debussy, Edgar Degas, James McNeill Whistler, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, among others.

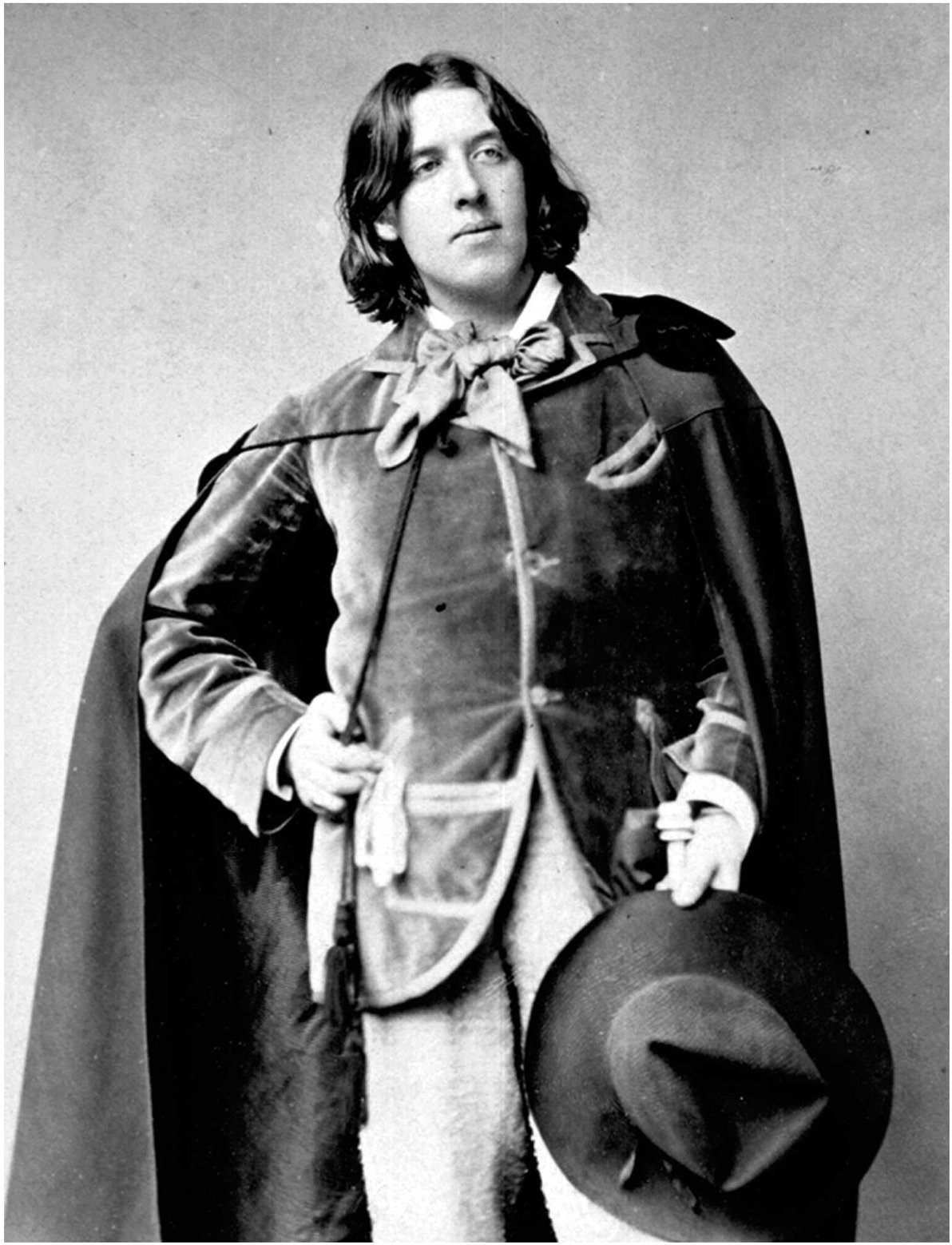

By the time Wilde went to London in 1879 at age 24, he was already known for his Æsthetic affectations and pithy quips. Caricatured by newspaper cartoonists as an effete dandy swanning around with a sunflower (the emblem of Æstheticism) in one limp hand, Wilde was perhaps the first person to be famous for being famous. By 1881, his photo was “in all the shop-windows—long hair, close-shaved face, loose cravat, & velvet coat, with his hands clasped under one cheek, gazing into vacancy,” reports the amused author of an 1881 letter excerpted in Wildeana, a book of epigrams, anecdotes, and other tidbits unearthed by the Wilde biographer Matthew Sturgis and recently published by Riverrun. “What has he done, this young man, that one meets him everywhere?” wondered the Polish actress Helena Modjeska, who’d earned her fame the old-fashioned way. “Oh yes he talks well, but what has he done? He has written nothing, he does not sing or paint or act—he does nothing but talk. I do not understand.”

For some, though, talking well was well enough. Conversation was an art in Victorian London, and Wilde was a Mozart of the form. The artist and writer Laurence Housman recalled him as “incomparably the most accomplished talker I had ever met,” mesmerizing his listeners with his “smooth, flowing utterance, sedate and self-possessed, oracular in tone, whimsical in substance, carried on without halt, or hesitation, or change of word, with the queer zest of a man perfect at the game.”

But how, exactly, did Wilde’s witticisms go viral in the years before he turned his hand to the plays that would make his best lines the talk of the town? Gregory Mackie, author of a study of Wilde forgeries that interprets them as perverse “fan fictions,” Beautiful Untrue Things: Forging Oscar Wilde’s Extraordinary Afterlife, thinks high society functioned as a kind of social media platform, disseminating Wilde’s most quotable quotes through its network of gentlemen’s clubs, society ladies’ salons, and dinner parties. “The upper classes were the celebrities of the day,” observes Mackie. “Wilde made that remark [about the blue china]at Oxford. Had he been a student at a working-class industrial institute, nobody would have cared.”

The blue china quip “was repeated everywhere—in the university at first, and then beyond,” confirms Sturgis. “A sermon was preached against it. It was used as the basis for a cartoon in Punch. It was adapted for a line in a successful West End play (The Colonel). It made Wilde realize the importance of the epigram—or the witticism—in forging a public persona. And throughout his career—particularly those early years, when he was achieving fame without really producing very much of real artistic value—it was his epigrams that propelled the process.”

One of his earliest sayings to be picked up by the press after he’d made his London debut, says Sturgis, was inspired by Wilde’s vexation at a high-society dinner party when the ladies lingered at the table, preventing him from lighting up the cigarette he craved. (A gentleman smoked after dinner, never during.) When his hostess lamented that a lamp on the table had been “smoking all evening,” Wilde observed, with impeccable deadpan, “Happy lamp.”

Wilde made a Faustian bargain with public relations, then in its infancy, and pioneered the art of personal branding. When Patience, Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic opera lampooning the Æsthetic Movement, came to Broadway from England in 1882, the producer, Richard D’Oyly Carte, worried it would flop because most Americans hadn’t heard of the “English Renaissance,” as the Æsthetes called their movement (with typical self-deprecation). Giving voice to reactionary, middle-class disdain for Æstheticism, whose radical ideas and provocative posing made it the counterculture of the day, Patience was an haute-bourgeois skewering of the Wildean type, personified by that “grandiose boob” Reginald Bunthorne, a precious Æsthete given to “dandyish dishonesty and nattering narcissism.” While not specifically a send-up of Wilde, Bunthorne was unmistakably Wildean in his “languid love for lilies” and his fondness for “uttering platitudes/ In stained-glass attitudes.”

In a masterstroke worthy of P. T. Barnum, D’Oyly Carte booked Wilde to lecture on Æstheticism around the U.S. in a contractually mandated get-up of velvet jacket, satin knee breeches, silk stockings, and patent leather pumps. Defending the status quo (as always), the press lampooned him mercilessly, but Wilde gave as good as he got, mastering the quick-draw comeback. Dublin-born and Oxford-groomed, he may have had the Irish gift of gab and a London urbanity, but America made him the Wilde we know. Turning the tables on his promoter, he took charge of his public image, selling cartes de visite versions of his famous Sarony photo shoot—the Victorian version of rock-concert memorabilia—after his lectures. “Lectures were a big deal in the late-19th century,” notes Sturgis. “They drew large crowds, up to 2,000 people in some instances.” Wilde became skilled at humbugging journalists with credulity-straining tales of superstardom, such as his claim that he’d had to hire a secretary to provide locks of hair for his adoring fans, and that the poor man was now bald, such was the demand. By the end of his tour, he’d raked in a considerable sum and reaped a windfall of press coverage—coin of the realm in the newly dawning media age. “I am impelled for the first time,” he told the amused audience at one of his lectures, “to breathe a fervent prayer: Save me from my disciples.” The press ate it up.

“The proliferation of the press during the late 1870s/early 1880s was a huge help to Wilde in spreading his name—and his sayings,” says Sturgis:

Dozens of new papers and periodicals appeared, to cater for the expanding middle-classes. And with them came a new type of journalism, that began to focus on personalities and personal anecdote. Part of Wilde’s genius was recognizing the opportunity that this presented. He determined to become the personal embodiment of Aestheticism. The distinctive tropes of Aesthetic dress (velvet jackets, capes, floppy ties) and the Aesthetic pose (sighing over beautiful things, draping oneself languorously on the furniture) were well established by the time Oscar adopted them. What he added to the mix was a natural humor in expressing his ideas. And that humor increasingly found its expression in his epigrams.

ONE OF WIT’S last refuges in our witless age is, incongruously, Twitter. To be sure, few tweets rise to the level of Wilde’s epigrams, and the social-media platform isn’t exactly James McNeill Whistler’s Peacock Room, plunked in the middle of Trump’s Idiocracy. But the wittiest tweets hew to the Wildean virtues of elegant economy and wry, lightly worn wisdom, with a paradox at the end, like a scorpion’s stinger. Inevitably, one wonders how Wilde himself would fare on social media. Would Twitter suit his style?

“Oh my goodness yes,” Gregory Mackie told me in an e-mail interview. “He’d be a Twitter king (queen?)! Just look at Stephen Fry. And sure, he’d not be averse to making money by ‘influencing’ as long as he could be seen to do it in a manner that was æsthetically superior to everyone else so engaged.”

Sos Eltis reverses the question, imagining Twitter in an alternate-history Victorian London. “His sayings would have zipped around the twitter-sphere in an instant, that’s unquestionable,” she says. “Wilde was cannily aware of public image and positioned himself with calculation and thought, remaking his image a number of times to remain just ahead of fashions and to ride a wave, breaking off just before it became too old hat. He was also extravagant and bad at budgeting, constantly in need of money, so he’d absolutely have worked out how to make money from his notoriety and fame.”

Wilde’s parables and paradoxes continue to beguile—and enlighten—because they still have much to teach us about our society and ourselves. We need the stiletto-sharp satire of his social criticism and the pointed insights of his moral philosophy—all wrapped up in those deliciously witty epigrams and aperçus—to puncture our hypocrisies and willful self-delusions, and to prick the demagogues, dunces, and sociopaths who dominate our age. “Patriotism is the virtue of the vicious.” “Whenever a man does a thoroughly stupid thing, it is always from the noblest of motives.” “Those who try to lead the people can only do so by following the mob.” “A mask tells us more than a face.” “It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances.” “A little sincerity is a dangerous thing, and a great deal of it is absolutely fatal.” “To be natural is such a difficult pose to keep up.” “To live is the rarest thing in the world; most people exist, that is all.” “An idea that is not dangerous is unworthy of being called an idea at all.” “There is no sin except stupidity.” “When the gods wish to punish us, they answer our prayers.”

The phrases that made Wilde a household name were meant to seem frivolous—airy nothings, like the bubbles in the Perrier-Jouët champagne he loved. “Life is much too important a thing ever to talk seriously about it,” says Prince Paul, in Vera; or, The Nihilists. Zen-like in their inside-out wisdom, Wilde’s observations are paradoxical at a meta-level, too. Weightless profundities, they treat the serious frivolously and take the frivolous seriously.* Be not deceived: Wilde’s wisecracks—literally, “wise jokes,” from the Irish craic, for “joking conversation”—are philosophical maxims disguised as one-liners, a paradoxical sting in their tails. “I made art a philosophy, and philosophy an art,” he declared in De Profundis. “I altered the minds of men and … awoke the imagination of my century. … I summed up all systems in a phrase, and all existence in an epigram.”

Not one given to false modesty, our Oscar. But then, the man who put his talent into his art but his genius into his life never claimed to be humble, and he managed to make immodesty charming in the bargain. During his disastrous second trial, prosecuting counsel insinuated that there was something unseemly about his passionate correspondence with Lord Alfred Douglas. “Do you think an ordinarily constituted being would address such expressions to a younger man?” said Mr. C.F. Gill, clearly thinking he’d sprung the trap. Wilde’s wit flashed from its scabbard: “I am not, happily I think, an ordinarily constituted being.”

* This, of course, is a distinguishing characteristic of Camp, the sensibility Wilde pioneered and which for generations of gay men before Stonewall was a way of signaling queerness to other gay men through bitchy wit, double entendre, and the flamboyantly theatrical inversion of gender roles and sexual norms. Defiantly queer, Camp mocks the Brad-and-Janet squareness of the straight world and sharpens the pain of the double life so many gay men have been forced to lead into a weaponized irony that winks at duplicity and double meanings. Camp sees life as theater, our social selves as masks. “To become a spectator of one’s own life is to escape the suffering of life,” writes Wilde, in Dorian Gray, a novel that’s all about hidden faces, secret selves.

Mark Dery is a cultural critic, essayist, and author of four books. His most recent is the biography Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey.