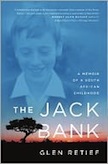

The Jack Bank: A Memoir of a South African Childhood

The Jack Bank: A Memoir of a South African Childhood

by Glen Retief

St. Martin’s Press. 275 page, $24.99

THE HISTORY of gay male literature in South Africa is select, and almost entirely white. To this reviewer, the grace and insight of its finest exemplar, Mark Behr’s novel Embrace, is now equaled by The Jack Bank (2000), Glen Retief’s first book. It is a fine attempt to do a number of impossible things: for Retief to explain to himself the origins of his own sexual attraction to nonwhite men; to account for his political maturation in the last days of apartheid; and to come to terms with the crude, bullying, yet also vital and exciting culture of the white Boers who surrounded Retief’s English-speaking family and populated his childhood.