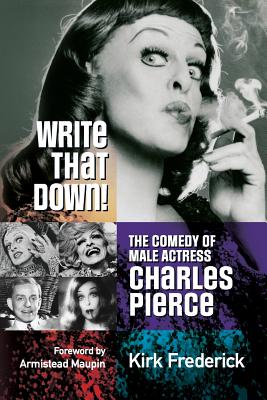

Write That Down: The Comedy

Write That Down: The Comedy

of Male Actress Charles Pierce

by Kirk Frederick

Havenhurst Books. 156 pages, $16.95

KIRK FREDERICK’S biography of “male actress” Charles Pierce (1926-1999) greets the eye with an iconic photograph of Pierce impersonating Bette Davis, his signature role. Other acting divas that he inhabited included Tallulah Bankhead, Carol Channing, Judy Garland, Katharine Hepburn, Gloria Swanson, and Mae West. Born in 1926 in upstate New York, Pierce became an internationally acclaimed female impersonator in the 1950s. Frederick’s biography offers a candid look at a career that spanned over fifty years, from Pierce’s humble start at the Pasadena Playhouse to his sold-out shows in San Francisco. This book gives a much-needed corrective to the outdated and envy-driven book by “John Wallraff” (aka John Dececco), 2002’s From Drags to Riches: The Untold Story of Charles Pierce. Wallraff’s narrative reads like a page from the National Enquirer, full of boozy nights, catty remarks, salacious gossip, and pornographic descriptions of Pierce’s sexual encounters. Wallfraff even claims to have written some of Pierce’s best dialogues, a claim Frederick’s book plainly refutes.

Charlie’s audiences regularly went into convulsions of laughter, and at one performance a wit shouted out, “He stole Bette’s dress.” At such spontaneous moments, Charlie would shout, as if to someone backstage, “Write that down!” His humor and emotional nuance were part of the act; it was as if Bette Davis was in the room with us. As we watched, we were mesmerized by the parade of personalities that came across the stage. Some of Charlie’s best routines have been painstakingly excavated and revived in Write That Down, which also includes some amazing behind-the-curtain anecdotes from his performances. The first night I saw Charlie perform remains etched in my memory to this day. I had just come from being forced to go to the Governor’s Ball in Miami dressed to the nines and sporting my mother’s white fox stole that she insisted I wear to complete my outfit. My longtime friend Ronnie Schwartz, a gay man, escorted me. After the ball we escaped to Miami Beach, where Ronnie had reserved a table at the Red Carpet, a gay cabaret bar. This was my first glimpse of Charles Pierce. That night he was sad, saying as he crossed the stage, “All I have is this moth-eaten old pink boa.” Then he leaned over the apron and in his classic Bette Davis voice spat out: “Hardly fit for a star. My kingdom for a real fur!” Spontaneously I jumped up, offering him the long, lustrous white fox fur I was wearing. Throwing me a dazzling smile, he wrapped it around himself and sashayed across the stage saying, “Peter, Peter.” Still in his Bette voice he warned: “Fasten your seat belts; it’s going to be a bumpy night” (a line he helped to popularize). Write That Down is a compilation of notes and reflections on Frederick’s personal and professional friendship with Charles Pierce. For me it is a delightful romp in nostalgia, but for younger readers unfamiliar with gay life in the 1950s, it may come as a revelation. It was a time when being gay was a crime. By acting upon your human desires, you were in the danger zone, at risk of landing in a prison cell or having your reputation ruined. There were no gay centers or positive environments save the ones we created for ourselves. There were clubs that allowed Charlie to perform, and he spoke for us all from a place of common gay experience, of being outsiders and outcasts from the heteronormative world. He traded in celebrity icons through his impersonations of Hollywood divas, who were hilarious but turned out to be vulnerable human beings, like us. What can one say? Charlie’s brain was a kind of keyboard of revolutionary, transgressive expression in drag. Charlie never got rich through his work—far from it—but he was a consummate performer who made all the difference for those of us who were young and coming out in the 1950s and ’60s. His legacy lives on in Kirk Frederick’s loving biography, which is recommended reading for both the laughter it provides and the gay American story it tells. Cassandra Langer is the author of the recently published biography Romaine Brooks: A Life (Wisconsin).  It still makes me smile when I recall Charlie (as he was always called) rolling those startling blue eyes, pursing his lips, and twirling his arm, the ever-present cigarette holder held high. He was brilliant at establishing his characters with a few gestures. The outfits helped too: he was dressed by queens living out their fantasies of female fashion in the feminine mystique closet. I will always think of Charlie wearing a shiny black satin dress impersonating Bette Davis. It still amuses me to remember him spontaneously entertaining friends like Jimmy Donahue, the Woolworth heir who regularly came down from Palm Beach with his entourage, including the comedian Martha Raye, to let loose and enjoy himself.

It still makes me smile when I recall Charlie (as he was always called) rolling those startling blue eyes, pursing his lips, and twirling his arm, the ever-present cigarette holder held high. He was brilliant at establishing his characters with a few gestures. The outfits helped too: he was dressed by queens living out their fantasies of female fashion in the feminine mystique closet. I will always think of Charlie wearing a shiny black satin dress impersonating Bette Davis. It still amuses me to remember him spontaneously entertaining friends like Jimmy Donahue, the Woolworth heir who regularly came down from Palm Beach with his entourage, including the comedian Martha Raye, to let loose and enjoy himself.