IT HAS BEEN almost three decades since the publication of my novel The Confessions of Aubrey Beardsley, which is being re-issued as a digital edition. This event coincides with the first major exhibition of Beardsley’s work in fifty years, which is scheduled to open at the Tate Britain in London in June (as of press time, after a postponement due to Covid-19). Another Beardsley show is slated to open in Paris at the Musée d’Orsay in October.

While preparing my novel for this new edition, I couldn’t help but reflect on the many years I spent researching Beardsley’s life, his art, and the circumstances that led to his downfall. It’s a story worth recounting as a reminder of the corrosive homophobia that devastated the private life and destroyed the public career of this brilliant artist.

My research began in the 1980s. I had written three contemporary novels and a play and was trying to decide what to tackle next. I have always been interested in gay history and initially thought Oscar Wilde would be the lead character in whatever this new work was going to be. Wilde’s trial and imprisonment for “gross indecency” was one of the seminal events of the late 19th century, a stark example of the persecution and criminalization of gay men that lasted into the 1960s. Wilde’s life was well documented, but no one had written in any detail about everyday gay life in late-Victorian England.

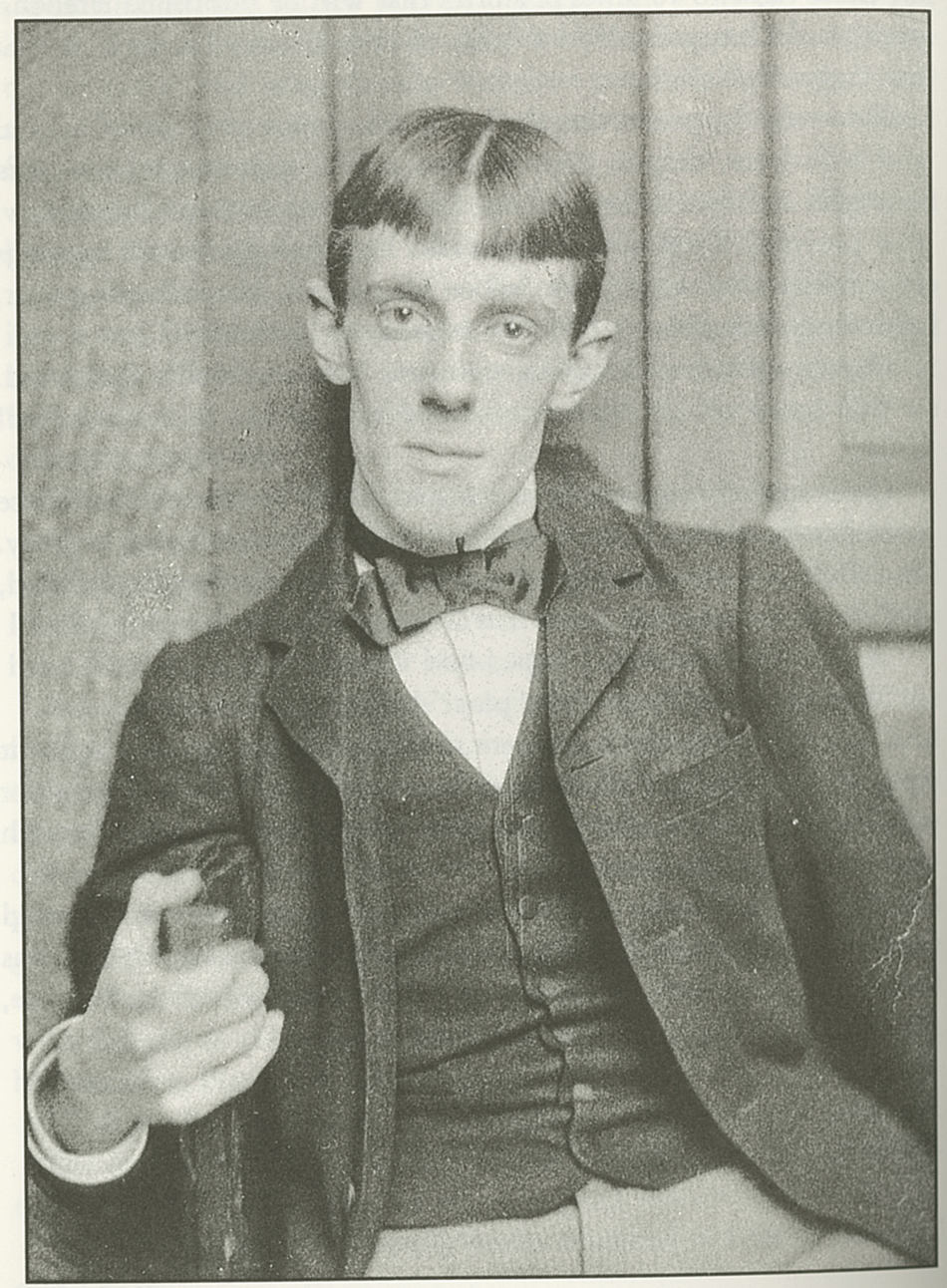

Beardsley, ca. 1894. Princeton University Library.

As I dug deeper and began to connect the dots, a shadowy picture began to emerge of the subterranean gay world that had flourished in England before gay men even knew what to call themselves. The word “homosexual” did not exist. “Sodomite” and “pervert” were the most common epithets used to vilify gay men. But among Wilde’s circle of educated gay friends, newly minted words like “invert” and “Uranian” were being used to identify and de-stigmatize themselves. Essays and poems on the taboo topic of same-sex love appeared in a magazine called The Spirit Lamp. Alas, these first stirrings of what today we might call “gay consciousness” or “queer identity” all but disappeared after Wilde was found guilty and sentenced to two years of hard labor. The “love that dare not speak its name” once again lost its voice.

The effect Wilde’s trial and prison sentence had on gay life was devastating at the time and lasted for generations. It was said that on the day of his arrest in 1895, every boat train leaving for the Continent was packed solid with terrified gay men fleeing England to escape arrest and prosecution. What a fantastic play that would make, I thought at the time. (I still think so.) Instead of having Wilde as my protagonist, I decided to shift my focus to someone whose life was compromised or ruined as a result of the Wilde scandal.

Aubrey Beardsley was an artist whose name comes up frequently in many of the books written about Oscar Wilde. The 1890s were, after all, later dubbed the Beardsley Period. The facts of Beardsley’s life are not nearly as well-known as those of Wilde’s, but their fates were inextricably intertwined.

At age 23, after a meteoric rise to fame, Beardsley’s career came to a swift and catastrophic end because of his association with Wilde. With his professional life in tatters, the only work the once-sought-after artist could find was with Leonard Smithers, a publisher with a lucrative sideline in pornography. Two years after his humiliating fall from grace, Beardsley, aged twenty-five, died of tuberculosis in Menton, France. Like Wilde, he had become an exile from his country and a pariah among his countrymen. In his final, agonized letter, written on his deathbed, he implores Smithers to destroy “all obscene drawings” that he had produced.

In 1966 Beardsley’s reputation changed overnight when the Victoria & Albert Museum in London mounted the first retrospective of his work. Beardsley’s strange, elegant, often androgynous images and his swirling Art Nouveau designs appealed to the countercultural zeitgeist of the 1960s, just as they had to late Victorians looking for a new visual thrill. When some of the “obscene” drawings surfaced, they became icons of the psychedelic era’s quest for sexual freedom and openness.

By the 1980s, most of Beardsley’s drawings had been reproduced in art books. To view the originals, I visited every museum and library in the U.S. and U.K. that owned Beardsley drawings or other materials associated with him. In photographs retrieved from dusty archives, the young artist with his severely cut bangs and center-parted hair stared at me with what looked like a dare in his eyes. He had obviously taken his reputation as a decadent dandy seriously and worked hard to maintain his image.

But how to bring this fascinating man to life? How to write about someone who suffered from incurable tuberculosis but still managed, against overwhelming odds, to create work of such unique and unforgettable brilliance that it came to define an era? And then there was the crash-and-burn aspect of his career because of Wilde, which had to be a major turning point in his story.

Beardsley and Wilde were not lovers, as some people assume. They were more like frenemies, alternately stroking and slapping each other’s ego. Beardsley, who was born in Brighton and grew up with none of Wilde’s social or educational advantages, was fiercely ambitious and used Wilde as a steppingstone to further his career. He actively promoted himself for the job of illustrating Wilde’s banned play, Salomé, knowing that it would make him famous (or infamous, as it turned out).

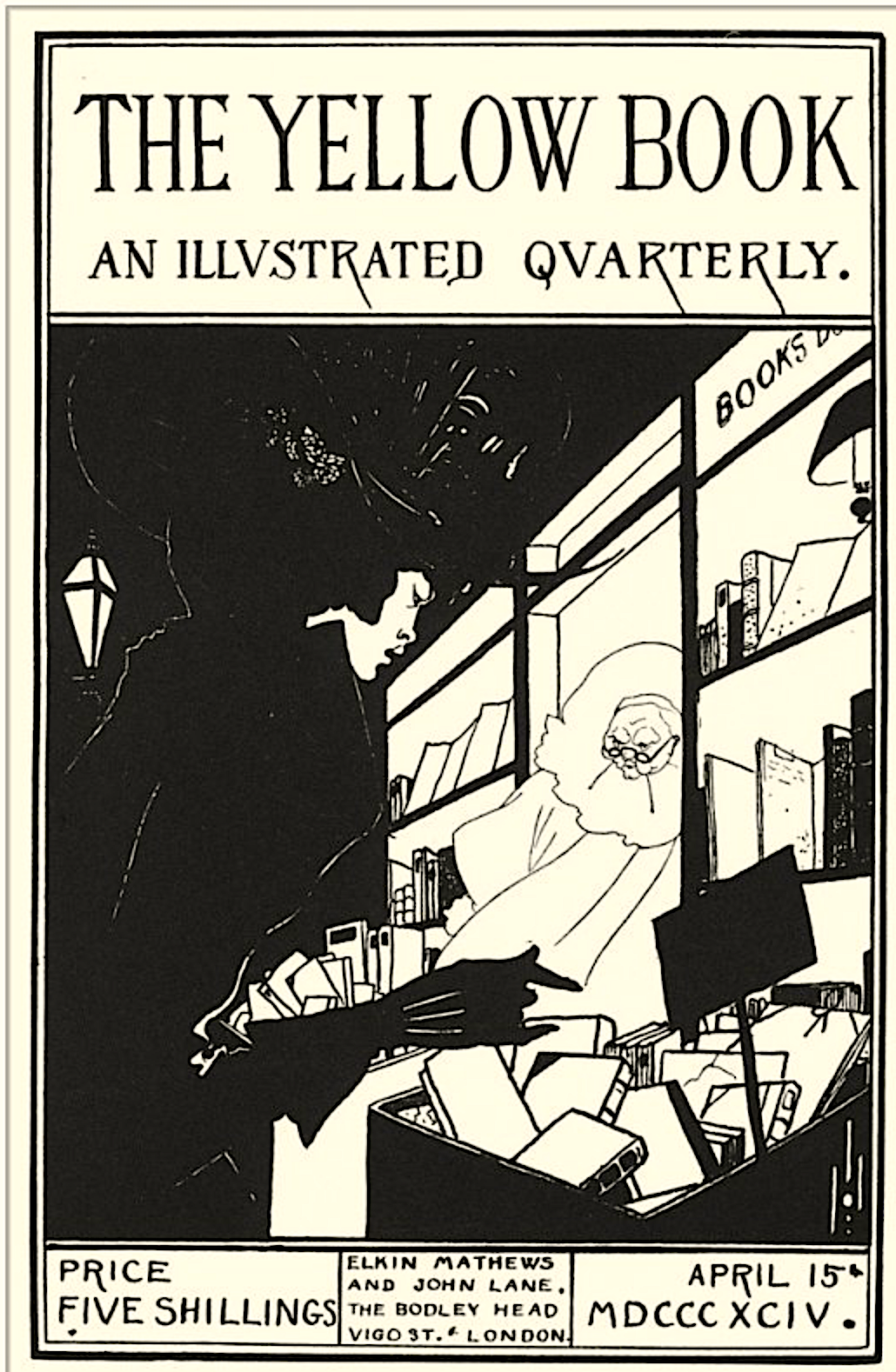

But Beardsley was wary of Wilde’s adoring group of acolytes and lovers and refused to become one of them. He put his unique artistic stamp on Salomé by creating bizarre Japanese-like fantasy illustrations that had little or nothing to do with Wilde’s “Byzantine” play. He drew even more attention to his illustrations by inserting sly caricatures of Wilde, as in Woman in the Moon. Wilde sensed that he was being mocked and was not amused. When he arrogantly claimed that he had “invented” Aubrey Beardsley, the latter retaliated by never asking Wilde to contribute to The Yellow Book, his influential art-and-literature quarterly.

Their competitive and contentious relationship, with its public sniping and acid-tongued bon mots, delighted the smart, artsy, gay-centric London crowd they both moved in. It ended in 1895, when the Marquess of Queensberry publicly insulted Wilde by accusing him of “posing as a somdomite [sic].” Wilde sued for libel, lost, and was arrested. A mob gathered to jeer at him as he was brought down in handcuffs from the Cadogan Hotel. Wilde, a voracious reader, was carrying a French novel with a yellow cover (most French novels at the time were published with yellow covers). Someone screamed that Wilde had a Yellow Book, prompting the enraged mob to advance on the offices of The Yellow Book and hurl rocks through the windows.

In the wake of the anti-Wilde hysteria that gripped London, Beardsley was sacked from The Yellow Book. His private commissions dried up. He lost the house in Pimlico where he lived with and supported his mother and sister. This all happened as he was dying of a disease that was expensive to treat and nearly always fatal.

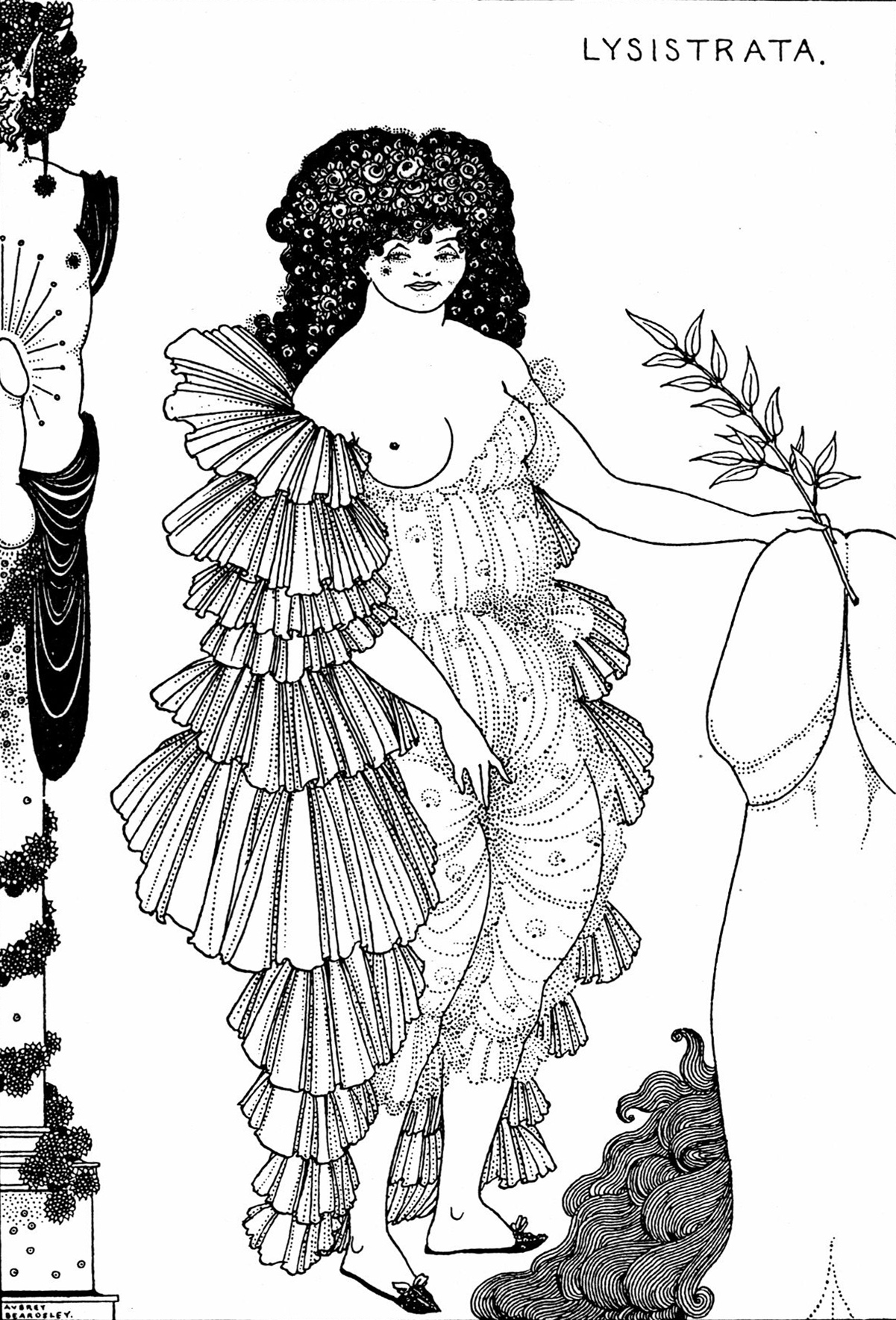

Desperate for money, he formed an alliance with the publisher Leonard Smithers, who raked in extra cash by publishing underground editions of bawdy and erotic classics. That was how Beardsley came to create his obscene drawings, the most famous being his illustrations for Aristophanes’ play Lysistrata. Looked at today in a post-Mapplethorpe world, the humorous, naughty, and coolly elegant Lysistrata drawings appear fairly tame, but by late Victorian standards they were hard-core pornography. Indeed Beardsley regarded them as such and begged Smithers to destroy them. Needless to say, the ever-untrustworthy Smithers held onto them, hoping to make more money after Beardsley’s death. Only a handful of wealthy connoisseurs of erotica saw any of these drawings during Beardsley’s lifetime.

Through the course of my research, I came to see Beardsley’s short, tempestuous life as a battle for artistic freedom in a world of stultifying conventions and condemnations. In that sense, his story is that of many modern artists fighting against the narrowmindedness of a public that knows nothing about art except how to destroy it. On the other hand, his desire to have the obscene drawings destroyed suggests that Beardsley was worried about his artistic legacy. His conversion to Roman Catholicism is another indication that he was struggling with issues of faith and redemption.

My five years of research on Beardsley and Wilde were marked by the growing hiv-aids epidemic and an upsurge in public homophobia. Repressive legislation like Section 28, forbidding the “promotion” of homosexuality in schools, was enacted in Thatcher’s U.K., and anti-gay rights battles were waged in cities and states throughout the Reagan-era U.S. Almost a century had passed since Wilde’s trial, but what, really, had changed? It seemed to me that Beardsley’s story, like Wilde’s, was as relevant as ever.

I first wrote about him in a play titled simply Beardsley. It had productions in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and London, but I felt there was still much more to say, and that it could only be said in a novel. Writing The Confessions of Aubrey Beardsley gave me the opportunity to widen the scope and create a richer, fuller portrait of the fin-de-siècle world in which Beardsley and Wilde lived and worked.

I prefaced every chapter with a drawing that illustrated Beardsley’s virtuosic and constantly evolving style, or a rare photograph that captured a period or person in his life. It is a novel written in the first person, in a hybrid form that’s a kind of autobiographical fiction. What this means in essence is that I took the bare biographical facts of Beardsley’s life and fleshed them out imaginatively. The most dramatic, I think, is the scene in which Beardsley and Wilde meet again, in Dieppe, after Wilde has been released from prison and is wandering about Europe under the pseudonym Sebastian Melmoth. They are both ruined men, former celebrities turned into penniless pariahs. It has been documented that they were both in Dieppe at the same time in 1897 and were aware of the other’s presence, but beyond that intriguing fact nothing is known. Imagining a final confrontation and what they might have said to one another was one of the most difficult and emotional scenes I have written.

I prefaced that chapter with an amazing drawing (below) that I believe sums up Beardsley’s ambivalent feelings towards Wilde. The subject of the drawing is Alberich, the sex-crazed dwarf in Wagner’s opera Das Rheingold. Alberich is eventually captured and subdued by Wotan and forced to give up his stolen treasure. Beardsley’s drawing of Alberich was done in 1896, a year after Wilde was sent to prison. It shows a furious Alberich trussed and immobilized but shaking a defiant fist in the air. The face is Oscar Wilde’s; the drawing is pure Beardsley.

Donald S. Olson is a novelist, playwright, and travel writer. His novel The Confessions of Aubrey Beardsley is being re-issued as an e-book by Lume Books.

Discussion1 Comment

I would refer anyone interested in Aubrey Beardsley to look at two books by Brigid Brophy: Beardsley and His World (pub. 1976) and Black & White: A Portrait of Aubrey Beardsley (pub. 1968). It is a sad state of affairs that Brigid Brophy has been ignored and largely forgotten over the years. It is worth remembering that during the 1960s and 70s she was one of the most prominant and forthright social campigners. Her absence from the history of the Gay and Lesbian Movement needs to be addressed – she was almost unique (as a married woman) to proclaim her bisexuality publicly, as well as her lesbian affairs.

D.R. Michael