THE FILM TOLKIEN, released last year and directed by Dome Karukoski, the award-winning director of Tom of Finland, sparked a bit of controversy by challenging heterosexual assumptions about J.R.R. Tolkien (1892–1973) through its portrayal of his intimate friendship with the young gay poet Geoffrey Bache Smith (1894-1916). The two met as teenage boys at King Edward’s School and deepened their bond at Oxford, where they probably were lovers.

Tolkien’s early years formed his creative imagination, beginning the journey that led to his masterpiece The Lord of The Rings. During this crucial period, it was Smith rather than Edith Bratt, the woman Tolkieneventually married, who was his artistic muse. Both young men were promising poets, and their poems from this period are rich in homoerotic imagery and themes.

World War I wrenched both away from Oxford and sent them to the Western Front in France. Smith’s tragic death at the age of 22 during the Battle of the Somme left Tolkien emotionally shaken—and determined to publish Smith’s collected poems, which he did under the title A Spring Harvest.

While scholars and biographers have emphasized the role of masculine fellowship in Tolkien’s life, they have stubbornly avoided the implications of his intimate relations with men. Homoerotic elements in his books have been ignored, with a few notable exceptions, including my earlier pieces in this magazine, “Sex and Subtext in Tolkien’s World” (Nov.-Dec. 2015) and “The Tolkien in Bilbo Baggins” (Nov.-Dec. 2016).

The true story about the relationship between Tolkienand Smith merits investigation from a gay-affirming perspective. The letters that flowed between them, often romantic in tone, open a window into their intimacy, as does their poetry. In the years after the young poet’s death, Tolkien was creatively inspired by the memory of Smith and the love they shared.

Dreams of Changing the World

Tolkien and Smith first met at the prestigious King Edward’s School in Birmingham, where both excelled as students. While the all-male school catered to the sons of aristocrats, Tolkien earned admission solely on the strength of his brilliance. An orphan by the age of twelve, he was forced to live in a lodging house and follow the guidelines of his guardian, Father Francis.

In 1900, Tolkien composed one of his first poems, “Wood-sunshine,” about fairies singing and dancing in a forested landscape: “Come sing ye light fairy things tripping so gay,/ Like visions, like glinting reflections of joy.” A brilliant philologist attuned to the cultural resonance of language, the young man can hardly have been innocent of the many layers of meaning evoked by the term “fairy.” It was in the 1890s that the word “fairy” began to be used as a synonym for male homosexuals. Indeed one of Tolkien’s teachers at King Edward’s, R. W. Reynolds, even warned his protégé that the word had been “spoiled of late.” Tolkien ignored the advice and continued writing poems about fairies.

Smith was two years behind Tolkien at King Edward’s and also took pleasure in flouting England’s conventions. He delighted in acting in the school’s annual “Greek Play.” A photograph of him in costume for his role in Aristophanes’ The Frogs shows a young man with a delicate, fey appearance and a dreamy expression. If Tolkienwere looking for a youth who fit the part of one of the fairies he loved to write about, he found its perfect embodiment in Smith.

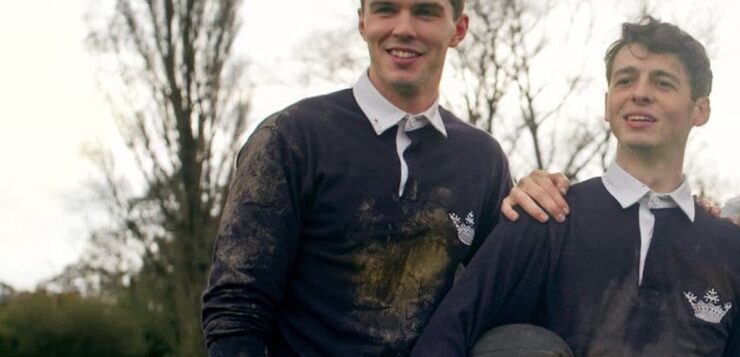

In its depiction of the young Smith, the film Tolkienoffers a charming portrait of a gay teenager in the Edwardian era. Adam Bregman’s Smith steals furtive, adoring glances at the young Tolkien, played by Harry Gilby. With sensitivity, the film depicts a schoolboy crush that serves as the prelude to a more enduring love story.

While the historical Smith similarly worshiped Tolkienin these early years, the outlet for its expression was the group that Tolkien formed with two other boys, which Smith would join later. The club exemplified what Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick called “homosociability” in its ethos, but the emotions expressed and the frequent use of the word “love” in its members’ correspondence could justify the term “homo-romantic” as a description of their interaction. The other boys included, first, Christopher Wiseman, a blond, barrel-chested youth who was an aspiring composer and whose connection with Tolkienalternated between a fierce rivalry and letters with strongly sexual overtones. The second was Rob Gilson, the son of the school’s headmaster. A gifted artist, Gilson fit the profile of an æsthete in the Oscar Wilde mold, with his fondness for embroidery, Renaissance painting, and theatrical productions.

The Tea Club members broke school rules by brewing tea and sneaking snacks into the library, where they engaged in passionate discussions about the role of art in civilization. When a more inviting space was discovered—an elongated compartment at the café at Barrow’s Stores in Birmingham center—the original name morphed into the Tea Club and Barrovian Society or T.C.B.S. for short.

For Smith, the youngest of the four, the underlying romantic tone must have been very welcome. Unlike Tolkien, who courted and later married Edith Bratt, Smith was never romantically involved with a woman. A brilliant conversationalist esteemed for his wit, he delighted in calling himself “G.B.S.,” initials better known as those of George Bernard Shaw. Precocious in his genius, Smith was confirmed in his vocation: he would become a famous poet. Smith introduced Tolkien to A. E. Housman’s A Shropshire Lad with its themes of natural beauty, the horror of war, and love between “lads.”

After Tolkien graduated from King Edward’s in summer 1911, his attachment to the T.C.B.S. did not diminish. Following his first term at Oxford, he returned to the school during the Christmas vacation for a seminal event in the club’s history: a performance of Sheridan’s The Rivals staged by Rob Gilson and featuring Tolkienin the role of the linguistically challenged Mrs. Malaprop. All four members of the club had pivotal roles. One can imagine Tolkien on the evening of the performance, flush with the prestige he brought back from Oxford and very fetching in his female costume. Perhaps it was on this night that Smith made a momentous decision: he would follow Tolkien to Oxford (even as the other two set their sights on Cambridge).

Oxford Interrupted

Tolkien entered Exeter College at Oxford in the autumn of 1911 on a scholarship to study Classics, and Smith followed two years later when he enrolled in Corpus Christi College, reading history. Corpus Christi was only a few minutes’ walk from Exeter, allowing late night conversations about poetry, philosophy, and language to extend past midnight in front of Tolkien’s fireplace (a favorite setting in Tolkien’s fiction). It is almost certain that Smith was a frequent overnight guest in Tolkien’s rooms in the period before he entered the university. He now called Tolkien “John Ronald” as a sign of affection.

Both young men fell in love with the beauty of Oxford. This was before the proliferation of motorcars, which Tolkien blamed for the destruction of rural England. Oxford was a unique blend of ancient halls, dreamlike spires, and lavish quadrangles surrounded by meadows, hedged fields, and views of the rivers Cherwell and Thames.

But Oxford offered much more than beauty and tradition; it possessed a secret. Evelyn Waugh, author of Brideshead Revisited, provides a vivid portrait of Oxford undergraduate life in his memoir A Little Learning. One of Waugh’s favorite poems was “Alma Mater,” Arthur Quiller-Couch’s pæan to Oxford, which begins with the enticing line: “Know you her secret none can utter?” The secret was the flourishing gay subculture that was whispered about all over England. Many young men opted for Oxford over Cambridge because they wished to experience the gay scene. Students still risked expulsion if they weren’t discreet, but the young men often engaged in defiant behaviors that expressed their contempt for authority.

Tolkien and Smith fit the profile of lovers at Oxford, engaging in youthful pranks. An especially riotous adventure that could easily have ended both men’s university careers involved the commandeering of a university bus. Here is Tolkien’s own account: “Geoffrey and I ‘captured’ a bus and drove it up to Cornmarket making various unearthly noises followed by a mad crowd of mingled varsity and ‘townese.’ It was chockfull of undergrads before it reached the Carfax.” This bus-hijacking adventure would fit well into Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited. Living dangerously was a way of shouting out to the world that they were playing by their own rules.

Oxford’s secret also found expression in the poetry that Tolkienand Smith composed during their undergraduate years. Tolkien’s feelings about men in many of these early poems are intense and haunting, with homoerotic elements expressed through imagery and symbolism. Often he employs fantastical characters, such as the star voyager in “The Voyage of Earendel the Evening Star,” to express his admiration for masculine beauty.

Smith’s poems are strikingly autobiographical. The most moving portrait of his love forTolkien is found in what is arguably his finest poem, “Memories.” Written after he left Oxford, it looks back longingly at Smith’s undergraduate years. The most intense lines describe his feelings about Tolkien (whose identity can be discerned through contextual clues).

One I loved with a passionate longing

Born of worship and fierce despair,

Dreamed that Heaven were only happy

If at length I should find him there.

Shapes in the mist, ye see me lonely,

Lonely and sad in the dim firelight.

To argue that Tolkien and Smith consummated a love affair during their Oxford years would be to challenge the status quo of Tolkien scholarship. But it would not be inconsistent with Smith’s poetry and with the homoerotic ethos that dominates so much of Tolkien’s works. (Take this passage from The Two Towers: “Sam sat propped against the stone, his head dropping sideways and his breathing heavy. In his lap lay Frodo’s head, drowned deep in sleep; upon his white forehead lay one of Sam’s brown hands, and the other lay softly upon his master’s breast.”) The Oxford years and Smith’s part in them were soon to be lost, but Tolkien’s memories remained, transfigured by his storytelling.

England entered the war on August 4, 1914, and that fall term Oxford was suddenly emptied out, with droves of male undergraduates responding to the nation’s call to service. There was intense pressure on Tolkiento join the throng. When he resisted, his masculinity was impugned. That he would ultimately serve was inevitable, but he decided to hold onto his life at Oxford for as long as possible.

Only nineteen when war was declared, Smith wrote feverishly throughout that fall and winter. One of his best poems from this period, in which he anticipates saying farewell to Oxford, is “Ave Atque Vale” (“Hail and Farewell”). The most poignant lines evoke the poet’s ineluctable sense that the door is soon to shut forever on the life he has loved so dearly:

At evening now the skies set forth

Last glories of the dying year:

The wind gives chase to relict leaves:

And we, we may not linger here.

A little while, and we are gone.

Smith’s poems from this emotionally fraught period are increasingly dark and more death-haunted than Tolkien’s verse. Perhaps he had a premonition that he’d be killed, but another explanation is that he was coming to terms with his sexual orientation and dealing with feelings of alienation. Later in the poem, the chilling line “Though grave-dust choke the sons of men” is repeated twice, underscoring his belief that he and many of Oxford’s sons were doomed. Many gay men in this era committed suicide, while others drank themselves into oblivion, like Sebastian Flyte in Brideshead Revisited. Oxford had provided an alternate reality that vanished after he left. It did not require the prospect of fighting in a war to make Smith suspect that survival was far from assured.

He enlisted in the army on December 1, 1914, foreclosing his chance to obtain his Oxford degree. Surprisingly, he joined before Tolkiendid even though the latter was nearly three years older. Smith’s voluntary enlistment seems mysterious: an outgrowth of his growing spiritual darkness?

A black-and-white photograph of Smith (above) shows him in the full uniform of his regiment, the 19th Lancashire Fusiliers. An attractive young man with searching eyes, his uniform flares beneath his tapered waist, giving him a decidedly fey appearance. Most striking is his left arm, poised almost with irritation on his hip, underscoring the ridiculousness of the whole costume and his ambivalence about wearing it.

His departure from Oxford, and from Tolkien, occurred some time in early 1915. Now that the two were physically separated, they became increasingly passionate about a new dream. If they were compelled to fight in France, they were determined to serve in the same regiment. Their shared vision of fighting alongside each other has elements of the homoerotic ideals of ancient Greece. Tolkien left no stone unturned in his quest to join Smith’s regiment.

The hopes of many months were dashed when, on July 9, 1915, Tolkienwas informed by the War Office that his request had been denied and that he was instead posted to the 13th Lancashire Fusiliers. “I am simply bowled over by your horrible news,” wrote Smith in a letter dated July 13th. Tolkien’s sadness and despair at the prospect of continuing to live apart from Smith found a voice when he wrote “The Happy Mariners” on July 24th. Probably Tolkien’s best stand-alone poem, it describes the tumultuous emotions of the main character (clearly Tolkien himself), who’s imprisoned in a tower made of pearl. There he listens to the voices of the mariners as they sail past on a journey into the mystical “West.” The poem exudes a sexual frustration and homoerotic yearning as the poet contemplates his fate and the sailors’ joy: “And maybe ‘tis a throbbing silver lyre,/ Or voices of grey sailors echo up,/ Afloat among the shadows of the world.”

For Smith, however, the war could not be transmuted into any kind of dream world. With his departure from England imminent, he made a quick trip home to say goodbye to his beloved widowed mother, Ruth Smith. In late November he made the crossing to France. Tolkien’s wish that they could make the crossing together was now only a lost dream. An echo of these events can be heard in The Return of the King: “Then Frodo kissed Merry and Pippin, and last of all Sam, and went aboard; and the sails were drawn up. … But to Sam the evening deepened to darkness as he stood at the Haven; and as he looked at the grey sea he saw only a shadow on the waters that was soon lost in the West.”

On the Western Front

Throughout most of 1916, Smith was in a far more dangerous military position than was Tolkien. Encamped in the trenches on the Western Front for many months, he was often stationed close to the River Somme or directly on it as the battle approached. Smith took to carrying Tolkien’s poems on his person as he went about his activities in the trenches. In January 1916 he was savoring Tolkien’s “Kortirion among the Trees,” an epic poem about the history of the fairies, and wrote to his friend: “I carry your last verses … about with me like a treasure.” It was common for soldiers in World War I to carry letters from their sweethearts in the pockets of their uniforms. Smith’s gesture speaks for itself.

One of Smith’s duties in the trenches was night patrol of the “No Man’s Land” separating enemy trenches. On the night of February 3, 1916, he wrote to Tolkien before heading out on patrol:

My dear John Ronald,

I am a wild and whole-hearted admirer, and my chief consolation is, that if I am scuppered to-night—I am off on duty in a few minutes—there will still be left a member of the great TCBS to voice what I dreamed. … You I am sure are chosen, like Saul among the Children of Israel. Make haste, before you come out to this orgy of death and cruelty.

May God bless you, my dear John Ronald, and may you say the things I have tried to say long after I am not there to say them, if such be my lot.

Yours ever, G.B.S.

This letter was found among Tol-kien’s personal belongings when he died in 1973.

Months on the Western Front caused Smith to become cynical about the war, but nothing could have prepared him for the carnage that enveloped him beginning on July 1, 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Rob Gilson, the gentle boy from the T.C.B.S. who had loved art and embroidery, was now an officer. Gilson led his troops blindly into No Man’s Land only to be killed on this first day along with an estimated 19,000 English soldiers, making it the deadliest day in the history of the British army.

In defiance of colossal obstacles, Smith and Tolkien had contrived to meet on the Western Front, adroitly tracking each other’s locations. On July 6th, still unaware of Gilson’s death, they had an extended rendezvous in the French village of Bouzincourt. According to Tolkien’s official biographer Humphrey Carpenter: “Smith stayed for a few days’ rest period before returning to the lines, and he and Tolkien met and talked as often as they could, discussing poetry, the war, and the future.”

What did the future hold for them? Tolkien’s marriage to Edith Bratt had finally come about on March 22, 1916. Smith, on the other hand, never talked of marriage. His mother, Ruth Smith, believed her son would return home to live with her after Oxford, for they enjoyed an especially close bond. When news of Gilson’s death reached Smith, he wrote to inform Tolkien, and their need to be reunited intensified. They arranged still more meetings while the war dragged on. They met in small French villages, taking walks in fields and wooded areas, reading and critiquing each other’s most recent poems.

In the fall, the Battle of the Somme gradually wound down. For Smith and Tolkien, the prospect of returning to England and to Oxford was appealing. But within a span of a few weeks, both men were hurled into the abyss. In late October, Tolkien fell seriously ill with trench fever caused by lice that festered in the seams of his clothing, passing a strain of bacteria into his bloodstream. Tolkien’s case resisted treatment, and he was sent back to England, where he wound up in a military hospital in Birmingham. Gravely ill and bordering on collapse, he was reunited with his wife and out of danger. Smith wrote that he was “beyond measure delighted” thatTolkien was safe in England and urged him to stay there.

On November 18, 1916, the Battle of the Somme was finally over. More than one million soldiers on both sides had been killed or wounded. (The Allies’ “victory”: about six miles of territory.) Now Smith, too, was apparently out of danger. On November 29th, he was walking down a road in the French village of Souastre when he was struck by fragments from a bursting German shell that had exploded several miles away. His wounds did not at first appear life-threatening, but after two days, gangrene set in, leading to an unsuccessful operation.

Smith died on December 3rd and was buried in Warlincourt British Cemetery. His mother Ruth opened her heart to Tolkien when she responded to his letter of sympathy. She implied that she knew Tolkien was similarly grief-stricken. “You can imagine what is this loss to me,” she wrote. “He had never left home until going to Oxford and we built many castles in the air of the life we would have together after the War.” Tolkien had no one to whom he could confide his grief. He composed an elegy titled “G.B.S.” that has never been published.

A Spring Harvest

In the same poignant letter, Ruth Smith planted a seed that she hoped would flourish. She asked Tolkiento begin assembling her son’s poems with the goal of publishing a book. Tolkien’s task was a daunting one. He himself had never been published except for a few poems in Oxford Magazine. Moreover, he was still seriously ill with trench fever and undoubtedly suffered from undiagnosed PTSD. In and out of hospitals throughout 1917, periodically hauled before military review panels determined to send him back to France, he was a physical and emotional wreck.

However, an extraordinary transformation had occurred internally. Within a few weeks of receiving the news of Smith’s demise, Tolkien’s imagination was suddenly soaring like the flying dragons he had loved since his King Edward’s days. He began writing his first full-blown book, titled The Book of Lost Tales, an underrated masterpiece that eventually morphed into The Silmarillion, which was the foundation for The Lord of the Rings. The hero of The Book of Lost Tales, Eriol, is clearly autobiographical (one of Tolkien’s middle names was Reuel), but he also possesses many of Smith’s traits. He’s a solitary, unmarried dreamer, deeply moved by poems and music, in search of a mystical past that exists on the edge of dreams. Homoerotic yearning is a dominant feature of Eriol’s character, expressed in symbols and dreams.

One scene in the recent film dramatizes Tolkien’s devotion to Smith’s memory and poetic legacy. Tolkien contacts Ruth Smith and arranges to meet her at Barrow’s Stores to discuss the publication of her son’s poems. When asked by Mrs. Smith if her son ever knew love, Tolkien has an epiphany, visualized onscreen by flashbacks and an otherworldly chorus composed by Thomas Newman.

One scene in the recent film dramatizes Tolkien’s devotion to Smith’s memory and poetic legacy. Tolkien contacts Ruth Smith and arranges to meet her at Barrow’s Stores to discuss the publication of her son’s poems. When asked by Mrs. Smith if her son ever knew love, Tolkien has an epiphany, visualized onscreen by flashbacks and an otherworldly chorus composed by Thomas Newman.

The shared vision of Tolkien and Ruth Smith was realized in June 1918 when the first edition of A Spring Harvest was published. Artistically, the collection is a masterpiece of English lyric poetry. Much like A. E. Housman’s A Shropshire Lad, a source of inspiration for Smith, A Spring Harvest is the poet’s autobiography as a young man. The cycle chronicles his coming of age as an Oxford undergraduate who experienced intense attraction to other men. The cruel interruption of the war tears the poet away from Oxford. In the final section of the cycle, the poet’s mood darkens, forebodings of death appear, and homoerotic themes become more overt.

“The Burial of Sophocles,” Smith’s most ambitious and technically brilliant poem, comes near the end. The final version was sent to Tolkienfrom the trenches. The Athenian wanderer in the poem is a portrait of Smith expressing his longing to escape from the world. At the height of his journey into the mountains, the wanderer comes upon a conclave of gods and is overcome:

He swooned, nor heard how ceased the choir

Of strings upon Apollo’s lyre,

Nor saw he how the sweet god stood

And smiled on him in kindly mood,

And stooped, and kissed him as he lay.

The kiss that Apollo bestows upon the wanderer who lies in a trance suggests that homoerotic fulfillment awaits in a world beyond this mortal coil.

A Spring Harvest has remained in print for more than a hundred years, reaching a select audience of scholars, Tolkien enthusiasts, and people fascinated with poetry from World War I. Geoffrey Bache Smith’s poetry also merits increased attention in the area of gay and lesbian studies.

His impact on Tolkien deserves our attention as well. Tolkien’s attempts to fill the void through drawing closer to Christopher Wiseman ended in failure. The volatile Wiseman sometimes openly courted Tolkien’s affections in letters containing the words “I love you,” but more often he shut the door on intimacy. In 1926, Tolkien met C. S. Lewis, and the two embarked on a long, complex, and often frustrating relationship. Mutual sexual attraction was apparently present, but circumstances did not permit sustained intimacy. In short, Smith could never be replaced in Tolkien’s heart.

Ultimately, of course, of greatest interest to millions of readers is the unique nature of Tolkien’s genius, and it is here that Smith has made his most enduring impact. His ardent faith in Tolkien’s destiny proved justified, beginning in 1937 with the publication of The Hobbit; and Smith’s spirit lives on in the three books of The Lord of the Rings through the passionate love that grows between Frodo and Sam. Smith deserves to come out from the shadows cast by longstanding homophobia in literary studies and to be given his rightful place in English literature as Tolkien’s most influential muse.

David LaFontaine is a professor in the English Department at Massasoit Community College.