BAYARD RUSTIN

BAYARD RUSTIN

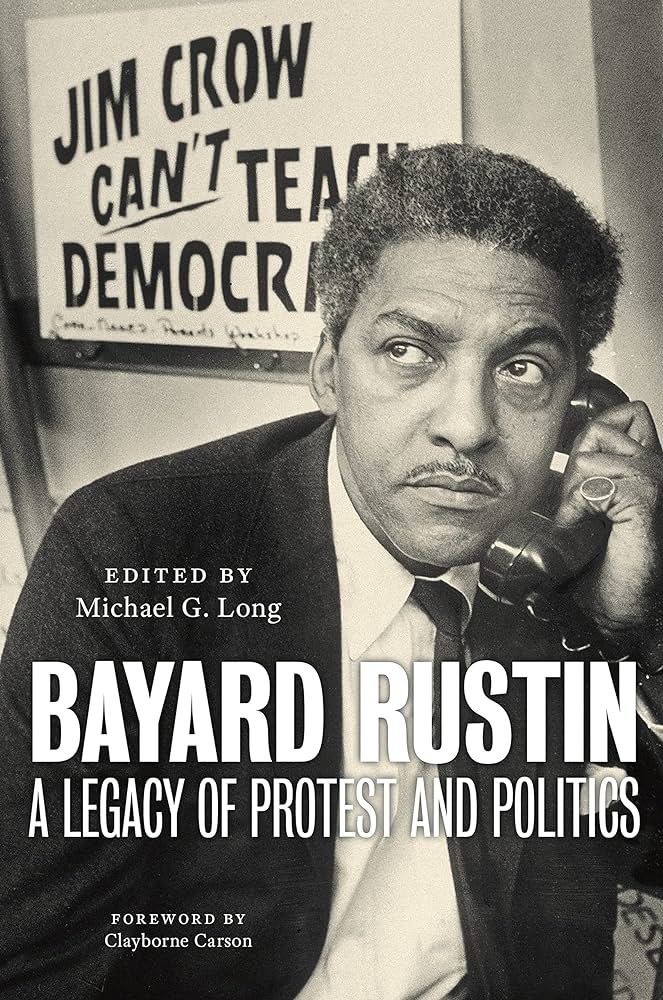

A Legacy of Protest and Politics

Edited by Michael G. Long

NYU Press. 256 pages, $27.95

BAYARD RUSTIN, strategist and spokesman for nonviolence, civil rights, and social justice, left an astonishing legacy. His extraordinary life story is that of a Black, openly gay activist who combined a pacifist’s vision with an electrifying presence to motivate political action in the mid-20th century. Rustin organized the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and his leadership continues to shape movements like the Black Lives Matter protests today.

Interest in Rustin’s life and work has been growing. Previous works of note include John D’Emilio’s 2003 biography, which probed the impact of Rustin’s work and his struggles to maintain a public leadership role, and a collection of Rustin’s impassioned correspondence titled I Must Resist: Bayard Rustin’s Life in Letters, edited by Michael G. Long and published in 2012. Long has now edited a collection of essays by a range of Rustin scholars titled Bayard Rustin: A Legacy of Protest and Politics.

Long is a former professor of religion at Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania. As he notes in his introduction to this stimulating collection, Rustin was a complicated figure with wide-ranging skills and achievements. The nineteen essays focus on Rustin’s work from the perspectives of history, political science, law, sociology, theology, cultural studies, and organizational activism. An incisive opening essay by political scientist Erica Chenowith, “Rustin’s Legacy of Civil Resistance in the U.S.,” gives a useful chronology of the activist’s work, including his conscientious objection to war in the 1940s, his steering of bus boycotts and early marches for freedom and integrated schools in the 1950s, and his leadership in the March on Washington, which prompted the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act of the mid-1960s. Along the way, he founded or helped form such civil rights groups as the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and he marshalled them into powerful coalitions. Agitating for passage of New York’s Gay Rights Bill in the 1980s, Rustin would declare gay people to be “the new barometer for social change.”

The essays supplement existing scholarship with details on how Rustin translated vision into action as a pacifist, a civil rights leader, and an advocate for social and economic justice. Focusing on his relationships with fellow leaders in those struggles, they offer fresh observations on Rustin’s experience as a gay man in an intensely homophobic era. In “Rustin’s Resistance to War and Militarism,” for instance, sociologist Sharon Erickson Nepstad describes his “earliest forays into activism [as]provocative nonviolent direct action.”

Born in 1912 to an unmarried teenager from a large family, Rustin absorbed an attitude of pacifism, tolerance, and inclusion from the maternal grandmother who raised him. He grew up in West Chester, Pennsylvania, a station on the Underground Railroad, where a Quaker family had purchased his great-grandparents’ freedom, and Quaker values informed his approach to life. Rustin adamantly opposed war, for example, an attitude that landed him in federal prison during World War II for “refusing military service and alternative civilian public service,” while exhorting others to do the same.

Five essays explore Rustin’s connections with other leaders, including his mentor, A. Philip Randolph, the intellectual and labor activist who founded the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first Black labor union in the U.S., in 1925. Another of his collaborators was African-American rights and grassroots activist Ella Baker, who joined Rustin to exploit the momentum of early bus boycotts in Montgomery, Alabama. And there’s an essay on Malcolm X, the African-American Muslim minister and activist, who publicly challenged Rustin’s pacifist stance but later became a close friend.

Disagreements marked other relationships too. “Rustin and King: Stony the Path They Trod,” by journalist and biographer Jonathan Eig, for example, describes the trouble Rustin had, trying to convince Martin Luther King, Jr., who was twenty years younger, to adopt a nonviolent strategy for his nascent civil rights crusade. The task wasn’t easy. Eig recounts Rustin’s shock at finding guns (intended for self-defense) when he first visited King’s Montgomery home, and notes the unrelenting persistence needed to convince King that nonviolence was the morally right, as well as more powerful, approach.

Rustin faced pushback for being a pacifist and even stronger resistance for being openly gay. Two essays explore this aspect of his life and experience. D’Emilio’s piece, “Troubles I’ve Seen: Rustin and the Price of Being Gay,” supplies a salient précis of the activist’s struggles during a time of blatant, intractable homophobia. “The decades during which he was most active as a radical fighter against racial injustice and for world peace—the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s—can reasonably be described as the worst time to be queer,” D’Emilio says, citing President Eisenhower’s 1953 executive order banning “sex perverts” from all federal and government contractor jobs. At the time, homosexual behavior was criminalized in every state. Rustin was apprehended more than once on “morals charges”—having sex with another man—and his arrest at a critical juncture cost him the backing of several civil rights leaders for a leadership role in the March on Washington. Fortunately, Randolph, who was overseeing the effort, knew Rustin’s involvement was critical and quietly put him in charge, with astounding results. As D’Emilio notes, “before the internet, social media, and texting from mobile phones, he and his team succeeded in getting 250,000 people to the nation’s capital.”

Rustin died in 1987. An insightful essay by his surviving partner Walter Naegle titled “The Legacy of Grandmother Julia Rustin” traces her influence. Julia and Janifer Rustin routinely welcomed Black luminaries to their West Chester home, among them James Weldon Johnson, who wrote the Black National Anthem “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” and activist, educator, and feminist Mary McLeod Bethune. Julia’s Quaker upbringing reinforced her belief in nonviolence and inclusivity, values she instilled in her grandson. Rustin saw his grandmother as “a dealer in relieving misery,” Naegle says, and must have sensed her open-mindedness when, as a young teenager, he took a chance and confided in Julia that he found himself attracted to his male classmates. Naegle reports that Rustin told him that her response had been: “Well, I suppose that’s what you need to do.”

The essays in this lively, thought-provoking collection amplify what is known of Rustin’s trials and achievements. They offer inspiration for progressives and democratic socialists today by showing how Rustin lived openly and without apology as gay man and a pacifist. The collection also amplifies Rustin’s voice, which rang out to ensure that marginalized voices would be heard. Reportedly, Rustin sometimes interrupted heated meetings by breaking into song, and clips of him singing spirituals in his melodious tenor voice can be found on YouTube.

Rosemary Booth is a writer and photographer who lives in Cambridge, MA.