Behind the Candelabra

Directed by Steven Soderbergh

HBO Films

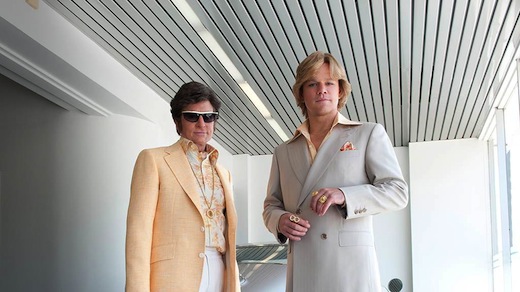

NO TV EVENT sparked the summer heat quite like Behind the Candelabra, the HBO biopic about Liberace’s love affair with Scott Thorson, a man more than forty years his junior. (The film was reportedly rejected by the major studios for being “too gay.”) Much of the fanfare involved the casting of Michael Douglas (now 68) as Liberace and Matt Damon as his kept boy.

The movie opens in 1977. For anyone born after that date, as I was, the name Liberace conjures a bygone era of easy listening, Las Vegas, and a gaudy kind of gayness. The name is also something of a dirty word in gay culture because Liberace denied his sexuality right until the bitter end. The pianist died in February 1987, three weeks after being hospitalized in Rancho Mirage, California. His private physician listed his cause of death as congestive heart failure, and his staff went on to claim that he died from “the effects of a watermelon diet.” (In the film, that absurdity is delivered by Dan Akroyd as Seymour Heller, Liberace’s manager of more than 25 years.) But the coroner’s office in Riverside County, in a rare move, rejected the death certificate, and—before Forest Lawn Cemetery could lay Liberace to rest—an autopsy determined that he died of cytomegalovirus pneumonia due to HIV.

The tabloids might not have pried open Liberace’s closet with such fervor had he not been so dishonest about his private life for decades. One year before his death, he published The Wonderful, Private World of Liberace (1986), which begins: “I wrote this book to show people who I really am.” Denial had long been Liberace’s default mode. “I have a general family audience appeal,” he once said, “and I don’t want to develop only a gay following.” In the film, Thorson returns one last time to Liberace’s deathbed in Palm Springs where, wigless and withering away, he tells Scott: “I don’t want to be remembered as some old queen.”

Liberace might have hated Behind the Candelabra for promoting just that memory. Still, it forces us to rethink his life on and off the stage. Long before there was Lady Gaga and her explosive brassieres, there was Mr. Showmanship, as he was known, and the battery-controlled gold and crystal candelabra emblazoned on his left breast pocket. Elton John, David Bowie, and Madonna all followed Liberace’s lead in proving that “presentation is everything.” Once the highest paid entertainer in the world, Liberace lived like Louis XIV, but his Hollywood home was the best example of what Liberace calls “palatial kitsch” in the movie. (Douglas, incidentally, nails the nasal timbre of Liberace’s voice and his wide, veneered grin.) The home included a Baccarat table crafted for an Indian Maharajah, a bed made from the carvings of Spanish artisans and covered with llama and ermine tails, a piano-shaped pool, and a custom-built, bullet-proof Cadillac.

Behind the Candelabra pays only scant attention to Liberace’s life prior to meeting Thorson. That’s a shame, because that life was a quintessentially American one. Like a gay version of Jay Gatsby, “Lee” grew up in the Midwest, changed his name numerous times, and relished what Fitzgerald once called a “universe of ineffable gaudiness.” Named after his mother’s favorite matinee idol, Wladziu Valentino Liberace was born on May 16, 1919, in the Milwaukee suburb of West Allis, Wisconsin. In the movie, his Polish American mother Frances Zuchowski is played by Debbie Reynolds, who was a friend of Liberace and helped him to keep his secret. The Liberace household was a musical one, though it fell apart in 1931 when Wladziu’s Italian father, a professional French horn player, ran off with a (female) cellist. The young Liberace played various beer joints and supper clubs in the early days of the Great Depression to support his family, and in 1939 “Wallie,” as he was then known, began playing with the Chicago Symphony and took the name Walter Buster Keys. In 1950, after touring the country with his violinist brother George, he changed his name once more, this time to Walter Valentino Liberace.

The following year was the annus mirabilis for Liberace. His first television show aired on August 7th and quickly became the nation’s most popular daytime program, even beating out I Love Lucy and Dragnet with a staggering 35 million viewers each week. With 178 advertisers, The Liberace Show was also a cash cow for its star. The prince of parlor music, Liberace was crowned as television’s first matinee idol. Years later, in 1970, he would publish his first cookbook entitled Liberace Cooks! Recipes from his Seven Dining Rooms. But it was in the living room that America’s fascination with Liberace first unfolded in all of it psychosexual glory. Dubbed “the greatest lover since Valentino” and “the candelabra Casanova of the keyboard,” Liberace cast a bizarre spell over his female fans, who were willing to suspend disbelief for at least an hour each week.

Liberace, for his part, was able to pull in $138,000 for a single concert at Madison Square Garden in 1954, landing him in The Guinness Book of World Records for the highest-paid piano player in history. In 1954, Variety marveled that “no male attraction has devastated the opposing sex in these terms since Rudolph Valentino. … [I]t’s readily seen that he is all things to all women.” All of which is not to say that Liberace was not ridiculed for his effeminate charm. Bob Hope once joked that Liberace was “such a delicate baby that instead of slapping him, the doctor patted him with a powder puff.” The press especially loved to take potshots at his pot belly. A New York Times review of the film When the Boys Meet the Girls (1965) commented that the movie includes a “gushy keyboard spray of Liberace, wedged in with a shoehorn.”

Even two lawsuits failed to slow Liberace’s stardom. The first came in 1956, when he sued The London Daily Mirror for referring to him as “He, She and It” and the “biggest sentimental vomit of all time.” The trial played out like a Wildean farce in the summer of 1959. He was even asked if he used scented or unscented lotion. Before swearing under oath that he was not homosexual, he told the court: “I’m against the practice because it offends convention and offends society.” Liberace won the suit not because he was unscented but because the jury members—one of whom winked at the performer after deliberation—agreed that “fruit-flavored” and other epithets were libelous under British law. The second suit came in 1957 when Liberace was awarded $40,000 in a libel case involving the Hollywood tabloid Confidential, which alleged that he propositioned a male press agent in three states. This time he won, not by proving he wasn’t gay, but rather that he wasn’t in Texas at the time. Whatever he earned in the Confidential case was lost in 1972, after he suggested in his autobiography that he and the actress Joanne Rio had been romantic. She sued and he lost. Liberace’s defenders still maintain that he never came out publically because of the London trial, where he had sworn under oath that he was straight.

Behind the Candelabra is directed by the great Steven Soderbergh who, at 26, became the youngest director to win the Palme d’Or at Cannes with Sex, Lies, and Videotape (1989). That was 25 years ago, and Soderbergh now claims he’s retiring from the movies to focus full-time on his painting. If that’s true, then this completes a sexy streak of films that includes last year’s stripper drama Magic Mike and this year’s Side Effects, a pharmaceutical thriller with a lesbian twist. Even more lurid and lavish than those, Behind the Candelabra is based on Thorson’s tell-all account of his bumpy ride with the piano man.

Thorson first met Liberace in his Las Vegas dressing room when he was just seventeen and living with a foster family. Liberace took an immediate liking to Thorson, who also grew up in Wisconsin and was seeking a father figure. More than happy to fill that role, Liberace even attempted to legally adopt Scott as his son before the two split up in 1982. By that time, he had undergone plastic surgery at Liberace’s request and developed an addiction to pharmaceutical cocaine, part of what Liberace’s doctor (hilariously overplayed by Rob Lowe) called his “Hollywood diet.” After Lee proposed an open relationship, a spiral of jealousy and amphetamines drove Thorson to a nervous breakdown and being thrown out of Liberace’s apartment. He later filed a $113 million palimony suit, which was settled for a fraction of that amount in 1986, and has since been in and out of prison for petty theft and drug charges.

At its core, Soderbergh’s movie plays out like a Frankenstein tale, right down to the operating room. Recreating Scott in his own image and confining him to his mirrored apartments, Lee makes a monster of his boy-toy, who metamorphoses from hunky naïf to vengeful brat. We also see Liberace having some professional highs and lows. In 1963, he nearly died from inhaling a gallon of the carbon tetrachloride routinely used to dry clean his jeweled jackets and costumes in an airless hotel room. In the hospital, where he was diagnosed with kidney failure, last rites were performed, but he survived and spent nearly his entire fortune in large cash gifts to loved ones and employees. He then made a miraculous recovery in time for Christmas morning and left the hospital nearly broke. In the movie, Liberace himself narrates this anecdote to Scott and describes his vision of a Catholic nun who “assured me I would live.” In short, Liberace casts himself as Christ in his very own passion play. And not to be overlooked: the ceiling of his Las Vegas mansion was a recreation of the Sistine Chapel with his smiling face painted among the cherubs.

The script by Richard LaGravenese hits all the right notes, presenting the full paradox that was Liberace’s life. Here was a man who lived for the limelight but spent his entire life in the shadows; who relished pornography and multiple sexual partners but who never dared to come out to the general public. Behind the Candelabra captures these dichotomies and suggests further that the closet wasn’t such a terrible place for those privileged few who were insulated by wealth and celebrity. Milestones in gay cinema such as Gods and Monsters and Brokeback Mountain portray how the closet, prior to Stonewall, was a lonely, even fatal, space of repression and loss. What’s truly devious about Behind the Candelabra is its suggestion that the closet once offered actual advantages for the rich and famous. It may have been lonely at the top, but the luxuries were almost limitless—including the ability to maintain the lie behind the screen of a carefully managed public image.

Colin Carman recently joined the English Department at Colorado Mesa University where he teaches British and American literature.

Discussion1 Comment

In his review of Behind the Candelabra, Colin Carman claims to be among those born after 1977. That explains his misguided remark about Liberace’s lifelong “dishonesty” about his sexuality. Those of us from the midwest and around long before 1977 remember when being gay was absolutely not an option. We saw people even suspected of being gay publicly and privately ridiculed, fired from their jobs, disowned by families and friends–careers ended. We were conditioned from childhood to believe homosexuals were all perverts or mentally ill or worse. Of course he denied being gay in the British lawsuit. In England as in many places in the US it was not only completely socially unacceptable but also illegal to be gay. You could go to jail or be sent to a mental institution for “treatment”! I was born in that era and was in my 40’s when I carefully and slowly came out. and still at the cost of some family and friends. I conducted myself no differently, but in some cases just knowing made it an issue for some. Mr. Carman needs to check his history books before judging the decisions of intelligent people from a different era.