Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life

Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life

and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey

by Mark Dery

Little Brown. 503 pages, $35.

For Gorey aficionados, this oddly titled doorstopper, Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey, by Mark Dery, which includes a bibliography, endnotes, and an index, will be welcome. The title is odd if the author means to imply that Gorey was only known posthumously, which is anything but the case. In addition to the 100-plus books he published in his lifetime, he was widely reviewed and interviewed in periodicals and other media, appeared on The Dick Cavett Show, had a cover on The New Yorker, and was profiled in The New York Times. The publication of his earlier books in the compendia Amphigorey 1 and Amphigorey 2 were bestsellers. In his later years he won awards for his theater sets on Broadway, notably Dracula. He wrote plays and revues that filled at least one Cape Cod theater, and his animated introduction to the PBS series Mystery!, which made him world famous, continues to be used to this day. To imply that Gorey’s fame is “posthumous” is thus far off the mark.

That said, the author shows how all of that came about, and does so clearly, step-by-step. Like most artists and writers, Gorey had a long, underpaid, and underappreciated apprenticeship, working in the crowded art departments of various publishers large and small. Still, that’s where he produced his first trials at what would become his signature books, and that experience would serve him well for the rest of his life.

But the author’s subtitle about Gorey’s eccentric life is more accurate and for many readers that may be the focus of their interest. For the most part, they will be disappointed in the results. Not that Dery hasn’t tracked down seemingly every human being who ever had contact with Gorey. He has; and their words—from Harvard classmates to publishing house art department denizens and various crafts-folk in those smaller theaters—tell us a great deal.

Dery also goes into detail about what Gorey did—and what he did not do—emotionally and sexually in his life. Not all that much, it appears. Early on, Gorey himself said of his sexuality that he was “neither the one nor the other, particularly.” The author points out that he had several “crushes,” and those were always on apparently heterosexual males. But Gorey did have several productive friendships with heterosexual men, who remember him fondly and don’t really understand what ended their relationship. “We drifted apart,” Peter Neumayer reports. So, Gorey’s longest and closest friends —aside from his adored cats—turned out to be women: his aunt, the female cousins whom he moved next-door to when he retired, and the author Alison Lurie.

His early college days seem to have set the tone for what would become his outward persona. Among his closest pals in those days were the poets Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery, gay men of the “gin and Judy” generation who became famous but who never came out publicly, or did so only much later when it was absolutely safe. On the other hand, they made little effort to appear conventionally masculine. Edward Gorey, with his high voice, campy intonations, vocal swivels and exaggerations, swish gestures, and wild clothing choices—eternally scuffed Keds sneakers, jeans, odd sweaters, colorful, often twelve-foot-long yellow scarves, and enormous fur coats—was an unmistakable sight at the New York State Theatre every night that a Balanchine ballet was on. There, amid his fellow balletomanes, he was comfortable and easily identified.

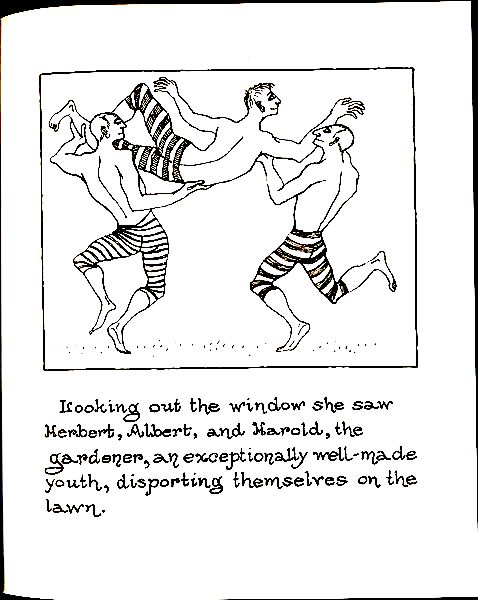

For those men who had come onto the scene and come out fully as gay, someone like Gorey might have been a major embarrassment. Except for the fact that he was Edward Gorey, author of those “forty small books,” whose effect was anything but small. The first one that I recall was The Curious Sofa (1961), subtitled “A Pornographic Work by Ogdred Weary,” a book about a piece of furniture that apparently induced eroticism in the user (in keeping with the ’60s dictum that “anything goes”). All in the most precise, dispassionate language, the message can be subtly lascivious, with Gorey’s characteristically static, but often quite suggestive, illustrations. The caption to the penultimate frame of the book, when seemingly all the possibilities of living creatures’ physical combinations had been exhausted, is: “And many were the barks and giggles.” The tone is perfectly restrained even when he’s detailing utter perversity.

One of Gorey’s great strengths was that he took everything completely seriously and simultaneously saw the humor in it. This trait reaches its height in books like The Insect God, The Hapless Child, and The Beastly Baby, where children may be homicidal or abducted and done in, often by outlandish creatures not even human, and—this is key—with complete impunity. It is a witty yet amoral universe that Gorey presents so charmingly. Stretching this into philosophy, one could call Gorey an existentialist who reminds us that some awful, unjustified fate or unwarranted calamity might befall any one of us at any time.

Since he was such a balletomane—he considered George Balanchine to be “God” and adored certain of “Mr. B’s girls” (but never his boys)—another small book, The Gilded Bat (1979), is a crucial stone in the Gorey edifice. In it, Madame Trepidovska (“once assoluta at the Maryinsky”) comes upon five-year-old Maudie Splaytoes gazing upon a dead bird in the street—her feet in perfect First Position. Maudie becomes her protégée, and when scenes with the ballet mistress ensue, Madame is hauled off. For years, Maudie trudges en pointe in the last line in the chorus. Finally, she has a solo role as the Enraged Butterfly in Le Jardin de Regrets. The Baron de Zabrus invites her into his world-famous troupe, and Maudie becomes a star. Gorey reports that “her life continued to be rather tedious,” except for Serge developing an “unlikely affection” for her. But before she can do anything about Serge, she is stopped when the Baron tells her, “only Art meant anything.” Ballets are written for her, especially “The Gilded Bat,” in which she attains immortality. Her tragic ending is spectacular and, like her career, avian. This book is both a fond nod at Gorey’s passion and a brilliantly realistic look at the life of an artist. Every page of Maudie’s artistic success is followed by another in which she is shown away from the stage, for example, in a drab apartment ironing her tutu.

One of the real failings of Dery’s biography is that he never explains why Gorey made the kind of art that he did, and what he might have been thinking as he tediously filled in the innumerable cross-hatchings, original plaids, and complex wallpapers of his illustrations. Of course, that many hours of busywork would have allowed him to go over and over the captions in his mind until he got them exactly right. After all, what sets his work apart from that of other artists is the interaction of the drawings and the captions; this is the essence of his genius.

Dery’s repeated attempts to explain or explain away Gorey’s lack of a sex life also lead him onto some strange paths. To describe the many “perils of gay life in New York in the 1970s,” Dery relies solely on Edmund White’s book City Boy (2009), and he quotes White as saying: “We were so afraid we wore whistles around our necks to call for help.” Really? For most gay men, Manhattan during what Brad Gooch has called “the Golden Age of Promiscuity” was an unprecedented playground, and the more dangerous the margins—like crumbling piers, abandoned buildings, and seedy neighborhoods—the more exciting the sexual action often became. But this is a minor cavil for an otherwise exceptional, one-of-a-kind biography.

Felice Picano’s latest fiction is Justify My Sins: A Hollywood Novel in Three Acts(Beautiful Dreamer Press).