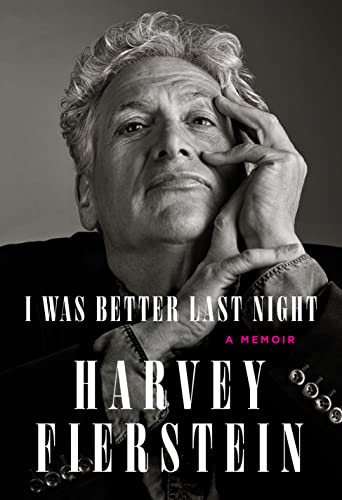

I WAS BETTER LAST NIGHT

I WAS BETTER LAST NIGHT

A Memoir

by Harvey Fierstein

Knopf. 400 pages, $30.

NEAR THE END of Harvey Fierstein’s large, fact-filled, anecdote-rich, entertaining memoir I Was Better Last Night is a photo of a sign bolted to a street pole that reads: “Accept No One’s Definition of Your Life. Define it Yourself.” And that is the writer–actor’s life story in a nutshell. This adage holds generally true for LGBT people of the Baby Boom generation, who pretty much had to create not only themselves but simultaneously a new queer language, society, and culture more or less from scratch. But Fierstein’s self-definition was more expansive than most, because from an early age it included gender explorations—something that was rare in those days (the 1960s), even if a large percentage of today’s young people are comfortable calling themselves nonbinary.

Another snapshot shows a young Harvey dolling himself up as a woman for Halloween trick-or-treating, and then realizing that this wasn’t going to fly with his tween friends in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. So, he smeared the lipstick and mascara and twisted the clothing and ended up as some kind of monster—to his friends’ applause. In many ways, Fierstein’s life and story are about un-smearing that boy’s face and clothes and just letting himself be—and damn the applause.

But doing that would turn out to be a long and hard-won battle, since Fierstein created and crafted an entire career around getting applause. The climax only happens toward the end of the memoir during a rehearsal for a Torch Song Trilogy revival, when his heterosexual brother Ron, with whom he has always been close, for the first time painfully understands that Mrs. Beckoff’s invective against her gay son Arnold in the play is verbatim the words their mother hurled at Harvey when they were kids. Later on, Fierstein deals more directly with that vituperation and concludes that he should have ignored “Jackie” and spent more time with his quieter and more understanding father.

But as so often happens, his pain was our gain, and the applause that Harvey sought wasn’t merely for costuming. As an art student in elementary school, he tossed off paintings that got so much attention that he realized he could gain approval with art. From high school to college he moved into pottery, creating popular pieces that somehow always included genitalia, whether male or female. He muses that if the college dean had allowed his work to be displayed in their school’s exhibition instead of banning them, pottery might have become his career. Instead, theater grabbed his attention. Despite his dyslexia, the words seemed to flow once he was onstage. Like many of us, his problem was with the gay and lesbian plays that were then current. Writes Fierstein: “Suddenly Last Summer, Fortune and Men’s Eyes, The Boys in the Band, The Children’s Hour, Staircase. Real [gay]life seemed a breeze compared to how it was expressed in literature.” But all that was about to change.

His years at Pratt Institute were odd ones. Of the staff he writes: “they watched you with cautious optimism, the way you watch a spinning quarter. You want it to spin forever but you know it will eventually fall flat or spin right off the table.” I Was Better Last Night wouldn’t be a credible stage memoir if there were not at least one suicide attempt and a decade of alcoholism.

While still in school, Fierstein began taking small parts in plays during Lower Manhattan’s 1970s creative explosion. He barely missed those crucial 1960s Greenwich Village laboratories for future American theater greats: Caffe Cino and the Judson Church. But he landed in the midst of the next best thing—Theater La MaMa and the various Theaters of the Ridiculous, with Ronald Tavel, Harry Koutoukas, Jack Smith, and Charles Ludlam. He took whatever parts needed to be filled just to be on stage, believing that “we were the underground, the elite forces of civilization, creators and keepers of art and culture.” Playwright Ronald Tavel and his producer brother Harvey became a second family, and soon Fierstein had moved into their basement flat in Park Slope.

This was an era of bold experimentation and anything-goes theater. As examples, this writer accompanied Warhol film star Ondine to the premiere of John Vaccaro’s When Queens Collide, and ten minutes into it I witnessed Ondine stand up and shout at René Ricard on stage that he was all washed up; Ondine could do it better. Ricard shouted back. Ondine jumped onto the stage. It turned out he was part of the play. At another premiere, Ondine carried two umbrellas. Sure enough, at the end of act one of The Fall of Atlantis, hoses were turned on the audience—only we two remained dry. Fierstein recalls complaining that the workshop audience didn’t get his one-act play, and Ron Tavel replying what must be that era’s motto: “It’s their job to catch up. Yours is to keep going.”

Never as radical as his mentors, Fierstein carved out a unique place in the American theater, and did so in a most timely fashion. To be sure, his first “real” play, the one-act monologue “The International Stud,” set in the back room of a notorious West Village gay bar, was outré for its time. When he wrote a second act, “Fugue in a Nursery,” the entire stage set was a big bed upon which the four characters of mixed genders and sexual orientations engaged in endless flirtation and pillow talk while musicians played a fugue offstage. But it was the third act, “Women and Children First,” that would later become his famous trilogy, and it was about as experimental as an episode of The Cosby Show. Arriving as a finished product in the early 1980s, Torch Song Trilogy was up there with A Chorus Line, Street Theater, Last Summer at Bluefish Cove, Follies, Bent, and other instant classics in LGBT theater.

It turned out Fierstein wasn’t an experimental playwright after all. In the book, he apologizes to Ron Tavel and to his younger self and others for not being able to continue their explorations. The Muses had their own uses for Fierstein’s particular talents and psyche. His career as an original playwright ended up being secondary to another passion. Ultimately it was as a larger-than-life stage actor and personality that Fierstein became famous and fulfilled. Consequently, the image that’s etched in most of our minds is Harvey Fierstein in full drag belting out Jerry Herman’s anthem “I Am What I Am” in La Cage aux Folles—so much so that it’s surprising to realize that, while Fierstein adapted the French play into a Broadway musical, he didn’t play the lead until a later Broadway revival. (George Hearn premiered the role.)

Success, fame, and awards would follow, as did more shows, out-of-town tryouts, collaborations, more success, fame, and awards. Anyone seriously interested in writing and staging plays, or in adapting books or films into plays or musicals, should read this book. It’s an eye-opening guide to how it can be done, how it should be done, and how it shouldn’t be done. Fierstein gives a terrific explanation of what is meant by a musical’s “book,” a concept that most people misunderstand. (It’s not just writing the spoken dialog; it’s creating the overall structure of the narrative, the actions of the characters and their personalities and interactions.)

The book is also a guide to dealing with other talented, famous, headstrong, and narcissistic people who are almost naturally involved in those shows. In his thorough discussion of La Cage aux Folles, Newsies, Kinky Boots and other musicals that passed through his hands, Fierstein shows what a professional he is, even in recalling what he and others did wrong. Indeed he’s not shy about castigating people whose behavior was unkind or over the top: Arthur Laurents was a tyrant during the making of the stage-bound La Cage; Gene Barry and Ginger Rogers were afraid of “catching” AIDS from gay cast members and had clauses about personal distance in their contracts. As for gays who remained closeted during our most dangerous times, he writes: “Those people collected the checks leaving the struggle for our rights to others.” Snap!

Although Fierstein got his star on Hollywood Boulevard, his film career exposed certain basic truths. (He also provides a smart evaluation of his gravelly voice and explains that his own early medical neglect was responsible for some of the problem.) He has many stories about these movies. For his pirate role in Kull the Conqueror, which he performed without a stuntman: “that’s me, tossed like Yom Kippur sins into the sea.” But he doesn’t touch on the question of why performances that worked so well on stage often did not succeed as well on film—including his role as Arnold Beckoff in the film version of Torch Song Trilogy.

He’s upfront about other roles that arrived at his door. At one point he was begged to do another revival of Fiddler on the Roof. The musical had originally thrilled him—Hasidim dancing on stage!—but, he asks himself: “Did I want to play Tevye again?” He did so, because “the long and short of it was that my ego won out.”

Comprehensive as the memoir is, I’ll bet many readers under the age of sixty will be running to their smartphones to look up the names he tosses off, since most aren’t given even a line of explanation. Similarly tossed off are the names of lovers and boy-friends. Toward the end of the book, Fierstein admits that his dream of settling down with a husband was simply not possible, and he’s made his peace with that, but none of the guys who may have been candidates—Paul, Sam, et al.—are even given last names. What’s up with that?

Other than Torch Song Trilogy, Fierstein wrote only one other “straight” play (i.e., not a musical), Casa Valentina, which was based on a carton of photos that he found of heterosexual men who gathered annually at a resort in the Catskills in the 1960s to wear women’s clothing for the duration of their stay. He labored long and hard on it, but “the play was fascinating, much too big, and lost its way.” It was eventually staged Off-Broadway and in smaller theaters around the country, but it never quite took off as he’d hoped. One reason might be that, in order to dramatically “solve” the play, Fierstein opted to make the accepting wife of one of the men his linchpin and to have the climax revolve around her. That left the larger questions of the play unanswered. When women like Diane Keaton and Lauren Hutton wear men’s clothes, they look great and they’re lauded for being bold and even sexy. But men wearing women’s clothes have to do it in secret at a lodge in the Catskills. Why is that? Is it the grip that patriarchy still has upon us? But these are not the kinds of questions that Fierstein addresses.

More crucial to future historians of the stage is how little Fierstein seems willing to reveal about how these shows “magically” came together. For example, Torch Song Trilogy wasn’t working in its first Off-Off Broadway run uptown, so John Glines decided to take it to Circle in the Square in Greenwich Village. A stellar cast of mostly unknowns like Estelle Getty and Matthew Broderick was assembled, and it became successful enough to move to Broadway. A pivotal player in that production was actor Joel Crothers, whose “résumé and photo appeared one day.” Crothers had replaced Robert Redford on Broadway in Barefoot in the Park, Neil Simon’s longest running show, and then went on to such success in daytime TV (The Edge of Night, Dark Shadows, etc.) that he had a Picasso at each of his residences. How did he happen to show up to audition at what was, by comparison, such a dinky operation? Fierstein either doesn’t know or won’t say.

I suppose because this is a “star memoir,” everything that happened did so because how else would Harvey Fierstein have become the star he became? Small criticisms aside, his new memoir is well worth reading.

Felice Picano’s latest fiction isJustify My Sins: A Hollywood Novel in Three Acts (Beautiful Dreamer Press).