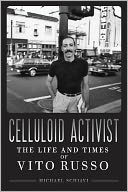

Celluloid Activist: The Life and Times of Vito Russo

Celluloid Activist: The Life and Times of Vito Russo

by Michael Schiavi

University of Wisconsin Press

320 pages, $29.95

WHEN, as a college freshman, I first picked up The Celluloid Closet, by Vito Russo (1946–1990), already a classic treatise about the presence of gay and lesbian characters in Hollywood films, I knew very little about film and had not seen many of the movies that it discussed. Nevertheless, I was instantly captured by Russo’s humor, his vivid descriptions of the movies he loved, and by the controlled anger that he brought to his analyses. This was not just a film buff showing off; instead, The Celluloid Closet brought to the forefront the voice of an informed, funny, politically aware gay activist.