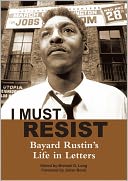

I Must Resist: The Life and Letters of Bayard Rustin

I Must Resist: The Life and Letters of Bayard Rustin

Edited by Michael G. Long

City Lights Books. 574 pages, $19.95

WHO WAS Bayard Rustin? Ask that question of most Americans, even those who claim to have a good working knowledge of modern U.S. history, and you’re likely to receive blank stares. March 17 of this year was the centenary of Rustin’s birth, an event marked by memorials and a fair amount of press coverage. But despite his admirably active life—more than four decades of protesting, writing, and speaking in support of a wide array of civil rights causes—Rustin, who died in 1987 at the age of 75, remains largely unknown to most Americans.

In the last decade or so, however, historians have started to pay more attention to Rustin. There have been at least three full-length biographies. In 2003 (for the 40th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech), Rustin was profiled in a documentary on public television, and a collection of his writings (the first ever) was published. This new collection of Rustin’s letters is also a publishing first, and it will undoubtedly do much to help more people appreciate Rustin’s contributions to the Civil Rights movement.

It also helps explain why he remains so obscure despite his key role in this movement. Rustin was openly gay at a time when this was a dangerous thing to be, so he chose to remain in the shadows for the most part. He played a supporting role for King and others in the movement, and seemed happy to play this role. And while Rustin was not one to hide, his relatively open homosexuality prompted others, including King himself, to distance themselves from Rustin when it suited their purposes.

It also helps explain why he remains so obscure despite his key role in this movement. Rustin was openly gay at a time when this was a dangerous thing to be, so he chose to remain in the shadows for the most part. He played a supporting role for King and others in the movement, and seemed happy to play this role. And while Rustin was not one to hide, his relatively open homosexuality prompted others, including King himself, to distance themselves from Rustin when it suited their purposes.

Yet Rustin was critical to the movement, and without him the 1963 March on Washington would surely not have come off as well as it did. King relied on Rustin’s organizational acumen to build the coalitions and pull the strings needed to make the march happen. More importantly, Rustin’s commitment to nonviolent resistance was a fundamental influence on King’s philosophy and on the Civil Rights movement as a whole.

Rustin came to his beliefs early. Abandoned by his parents, he was raised by his maternal grandparents, both members of the Religious Society of Friends, who educated him in the Quaker tradition and instilled in him a commitment to nonviolence, racial justice, and community service. This foundation shaped Rustin into a crusader with a vision of social justice that was not limited to racial issues—he was, for example, a committed conscientious objector, a champion of Israel, and an early opponent of nuclear weapons.

It was Rustin’s principled refusal to serve in the military that first landed him in prison, in 1944. Once there, he soon established himself as a “troublemaker” by promptly sending the warden long letters demanding desegregation of the prison. Rustin made it clear that he would not remain passive in the face of injustice, and prison authorities took notice. In a letter the warden wrote to the director of the U.S. Bureau of Prisons requesting Rustin’s transfer to another prison, the prisoner is described as an inveterate agitator. One time, for example, Rustin rallied fellow inmates of color by singing Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” through the prison’s pipe system, a performance greeted with loud applause and cheering.

Adding to these antics were reports about Rustin having oral sex with other inmates or propositioning them for it—reports that prison officials were all too happy to use to discipline him. Though Rustin protested his innocence, his friends and associates seemed to see some truth in the accusations. A. J. Muste, Rustin’s mentor from the anti-war movement, and Davis Platt, his lover at the time, each wrote advising him to subdue his sexual urges for his own good, and for the sake of his public reputation.

Upon release from prison, even as he was building a name for himself by organizing anti-segregation protests and boycotts, Rustin’s sexual activities continued to undermine these efforts. Arrests for “lewd conduct” in 1946 (in New York City) and 1953 (Pasadena) gave ammunition to those in the movement who were already uncomfortable with having a known homosexual in their midst. In a pattern that seemed to mark Rustin’s career, each time his sexual activities forced him to resign from a key leadership position, his undeniable value to the movement would eventually be acknowledged and his position restored.

Following his triumphant success with the 1963 March (accolades included a cover photo on Life magazine), Rustin caught the attention of the FBI. Like King, Rustin was the subject of a covert and extensive surveillance effort, for which J. Edgar Hoover obtained the approval of Attorney General Robert Kennedy. Declassified letters between Hoover and his agents, included in this collection, offer chilling details of how closely Rustin, King, and others were monitored, and how active the agency was in trying to undermine and discredit the Civil Rights movement. The details can be sobering, such as an account of Kennedy at a private dinner party referring to Rustin as “that old black fairy.”

The letters in this book, which represent only a portion of Rustin’s prolific output, provide a detailed, vivid, and often surprising look into his life and mind. They reveal Rustin’s commitment to speaking the truth to power, which he encouraged in correspondence with students, citizens, and politicians, including every president from Truman to Reagan. Toward the latter part of his life, Rustin became a kind of elder statesman not only of the Civil Rights movement but also of the Democratic Party. Former President Johnson and Senator Edward Kennedy, among others, counted him as a friend.

Although Rustin championed a wide array of political and human rights causes, only late in life did he advocate for gay rights. His life of resistance sprang not from being black or being gay, he stated in a late letter, but from his “Quaker upbringing … [and]the concept of a single human family and the belief that all members of that family are equal.” Rustin devoted himself to this human family around the world, and the world is a better place for his having been here.

Jim Nawrocki is a freelance writer based in San Francisco.