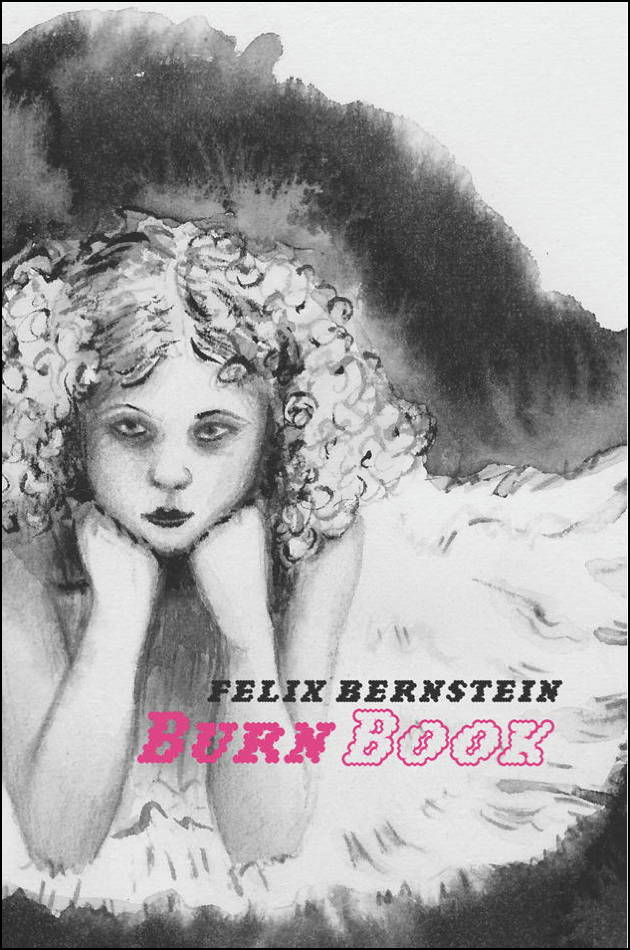

Burn Book

Burn Book

by Felix Bernstein

Nightboat Books. 117 pages, $16.95

WHAT PUSHES a poet forward? What energizes her words? Felix Bernstein has brilliantly summed up his impetus. “I want the fear of people opening the book to some random page and thinking that perhaps I don’t have my act together and that I’m not smart.” Ambiguous and complex, this sentence both defies and challenges the reader who may have stumbled upon it. The author is neither stupid nor clueless, yet the sentence is scrambled and unbalanced. Who, for example, is afraid? Is it the author, or the reader who is flipping through the book? If it’s Bernstein who’s afraid, why is he more afraid of the casual reader than of the serious one who would attend closely to the book? And of all the things to be afraid of, why is he particularly concerned about appearing smart and with his “act together”?