A Very Queer Family Indeed: Sex, Religion,

A Very Queer Family Indeed: Sex, Religion,

and the Bensons in Victorian England

by Simon Goldhill

Chicago. 337 pages, $35.

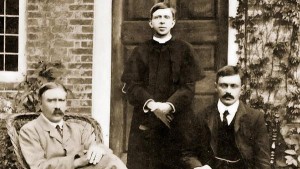

THE BENSONS were a family in Victorian England that produced an astonishing number of extraordinary individuals, starting with Edward, who became the Archbishop of Canterbury, his wife Minnie, who charmed a Prime Minister, and their six precocious children, notably E. F. Benson, who wrote the popular “Mapp and Lucia” series of novels, and Margaret Benson, an Egyptologist of great renown. But what makes the Benson clan so unusual is that collectively they embodied a range of the newly emerging sexual identities that we recognize today. Moreover, every member of the family had a passion to write—diaries, letters, biographies, memoirs, essays, and novels. In some 200 published works by the six Benson siblings, they analyzed their society and one another, revisited pivotal moments in family history, and commented privately upon each other’s self-delusions.

Writes Simon Goldhill in A Very Queer Family Indeed: “For the Benson family, there is a constant redrafting of the self, in conversation, in narrative, in writing—and in the eyes—the writing—of each other.” What’s more, having lived through the Cleveland Street scandal, the trials of Oscar Wilde, the Maud Allen libel suit, the Radclyffe Hall obscenity trial, and the public debates over the theories of sexual behavior advanced by Havelock Ellis, Krafft-Ebing and Freud, the Bensons offer social historians an unusually rich vein to mine regarding the emerging categories of modern sexual identity from 1853 (when Edward proposed to his twelve-year old cousin) to 1940 (the year that Fred, the final survivor, died).

While the most socially prominent member of the Benson family was undoubtedly Edward, who became the Archbishop of Canterbury and was the subject of hagiographic biographies by two of his sons, the family patriarch was a more shadowy figure than his progeny. This is because Edward’s diaries were burned after his death, presumably to erase any evidence of the spiritual doubts that he recorded but never dared to acknowledge publicly while alive. Instead, more than half of Goldhill’s book is devoted to Minnie, and her eldest surviving son Arthur, both of whose extensive diaries provide a wealth of information about their inner lives.

Prime Minister Gladstone famously quipped that he couldn’t decide whether Minnie was the cleverest woman in England or in all of Europe. Indeed for Goldhill her importance overshadows that of her husband. Goldhill notes that “she was renowned for the fascination and attractiveness of her conversation, not as a wit firing off glittering bon mots, but as an attentive, engagingly personal fabricator of a tent of intimacy through talk.” A spiritual crisis following the death of her eldest son from meningitis while a schoolboy left her with a far stronger faith than her clergyman husband. Ironically, it was this faith that allowed her to pursue women of similarly pious character who “fascinated” her even while stimulating her spiritually. At the same time, she called upon God to help her to resist the persistent temptation of “carnal aberration.” For example, writing in a fragmentary style that echoes in places Augustine’s Confessions, Minnie reviews the progress of her love for a woman that she met at a German spa:

Then I began to love Miss Hall—no wrong surely there—it was a complete fascination—partly my physical state [of weakened health], perhaps—partly the continuous seeing of her—our exquisite walks together. … I have learnt the consecration of friendship—gradually the bonds drew round—fascination possessed me … then—the other fault—Thou knowest—I will not even write it—but, O God, forgive—how near we were to that!

How would her family come to understand the nature of her passionate relationships with other women, oftentimes obsessing to the point that she ignored her children entirely? Not surprisingly, following Minnie’s death both Arthur and Fred published competing biographies of their mother in which they offered conflicting interpretations of the nature of her relationship with longtime friend Lucy Tait.

Arthur Benson, a close friend of literary lions Edmund Gosse and Henry James, shared with both a preference for reticence as he struggled to reconcile his private desires with Victorian society’s regard for public forms. Significantly, Arthur did not begin keeping his voluminous diary until the year his father died, as if Edward’s passing freed him to begin exploring his inner life at last. In these diaries he emerges as the most tortured of the siblings, going in circles as he searched for certainty in matters both sexual and religious, often sounding like T. S. Eliot’s Prufrock. (“Do I dare to eat a peach?”) His journals—no portion of which has been published previously—record his struggle to find words for the feelings aroused in him by other men, as well as his speculation as to what he should be called if he went so far, but no farther, with another man: a lifelong mental game of “what if?”

In a trenchant analysis, Goldhill explores the language of anguished uncertainty that runs through Arthur’s journals, concluding that, in both his sexual life and his religious engagement, “reticence—the awareness that he might not be sure and must not give himself away—is the watchword.” Indeed, Arthur was so paralyzed by the compulsion to dissect the basis of his every feeling and belief that even as he felt the onset of what would prove a fatal heart attack, rather than call for help he reached for a pen to record his sensations.

Youngest son Hugh emerges as the most colorful member of the family. Shortly after his father’s death, Hugh publicly rejected the archbishop’s legacy by converting to Rome and writing a series of quasi-historical novels that melodramatize the persecution of Roman Catholics under the Tudors and the Stuarts. To the shock of his late father’s many admirers, he fashioned himself as that very same mixture of Catholic-infused æstheticism and suggestively homoerotic decadence that his father’s brand of “muscular Christianity” was designed to combat. Hugh’s love of bathing naked with other men and his close ties with Frederic Rolfe demand greater attention than Goldhill accords them. (Who would not want to read more about a man who, after their falling out, was satirized in print by the obsessive Rolfe as “a stuttering little Chrysostom of a priest [who]did not aspire to control creation, but he certainly nourished the notion that several serious mistakes had resulted from his absence during the events described in the first chapter of Genesis”?)

Goldhill is well known in classical circles for his books on Greek tragedy, but is probably best known to readers of these pages as the author of Foucault’s Virginity: Ancient Erotic Fiction and the History of Sexuality (1995), in which he analyzes the rambunctious representation of sexuality—particularly male same-sex acts—in early Greek novels. In the process he offers important qualifications to Michel Foucault’s influential three-volume History of Sexuality. In A Very Queer Family Indeed he accomplishes something equally radical by serving up six characters in search of, not an author, but a sexuality.

Goldhill challenges the traditional image of Victorian society’s exclusive emphasis on family life and heterosexual love by demonstrating how the Benson clan, while living at the center of the social establishment, both individually and collectively violated these norms and effectively got away with it. But the Bensons also dramatize the dilemma of late 19th- and early 20th-century individuals caught between “new psychologies, new sexualities, and old moral certainties.” In a period of shifting morals, the Bensons (whom Goldhill wittily labels “a family of graphomaniacs”) wrote compulsively about feelings and desires for which they could never find a satisfactory name. They were, in Goldhill’s phrase, exiled to “the periphrases of propriety.” It’s little wonder that Minnie, Arthur, and Maggie suffered breakdowns, and that Edward and Hugh died in middle age.

Under the guise of a family history, Goldhill has fashioned a compressed, highly readable social-sexual history of the emergence of modern sexual identities. And yet, for all the deft analysis of what he terms the Benson “family dynamics of a struggle over sexuality,” I finished this book with the uneasy sense that something, or someone, of importance was missing. And it was Fred, the Benson who embodied another emblem of a certain sexual identity: camp. Fred’s style of camp included active resistance to the tyranny of heterosexuality—what we call heteronormativity—that still prevails today. The strategy of reticence to which Minnie and Arthur subscribed gradually faded after Stonewall. Unlike his reluctant siblings, Fred chose to follow the example of Oscar Wilde by donning the protective coloration of frivolity as a strategy to resist religiously authorized homophobia. More than a form of revolt against his father’s moral earnestness, as Goldhill suggests, Fred’s carefully fashioned insouciance was an act of outrageousness on a par with Algernon Moncrieff’s delight in cucumber sandwiches—that is, a focus on the trivial that effectively called attention to something significant by seeming to ignore it entirely. Fred’s camp deserves an analysis equal to Minnie and Arthur’s reticence and Hugh’s religious ceremonialism.

Raymond-Jean Frontain is professor of English at the University of Central Arkansas.