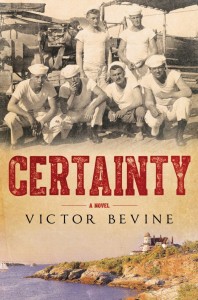

Certainty

Certainty

by Victor Bevine

Lake Union Publishing

339 pages, $10.99

AMONG THE FIRST gay scandals to reach widespread public consciousness in the U.S. was the Navy’s investigation into homosexual activity at its Naval Training Station in Newport, Rhode Island. Taking place in the immediate aftermath of World War I—thus following on the heels of both the massive wartime build-up of army and naval forces and the brief but devastating flu epidemic of 1918, which hit the armed services especially hard—the investigation shed a glaring light on “immoral” sexual activities either at the training station or within the town of Newport. The town was, of course, long the summer residence of America’s well-heeled “Four Hundred.” Upper-crust society would not have been happy to learn that their summer playground was also the haunt of “fairies” plying their trade on the Cliff Walk.