The Judas Kiss

A play by David Hare

Directed by Neil Armfield

Ed Mirvish Theatre, Toronto,

March 22–May 1

Brooklyn Academy of Music, NYC,

May 11–June 12

THE MOST POPULAR playwright of his day, Oscar Wilde’s professional reputation was temporarily overshadowed at the end of his life by his private notoriety—as either sexual deviant or sexual martyr, depending on your viewpoint—when he was convicted of “gross indecency,” a Victorian term for minor acts of homosexuality. The charge was brought against him by the Marquess of Queensberry, who also happened to be the father of Wilde’s young lover, Lord Alfred Douglas. That part of the tale is well known. What is often forgotten is that Wilde had the Marquess arrested first, for libel, after he accused Wilde of “posing as a somdomite [sic].” Wilde’s decision to press charges was supported by a number of his close friends, most notably the vengeful Lord Alfred, who hoped to get back at his father. Regardless of motive, it was not a smart move, as Queensberry was forced to prove his allegations in court, resulting in a second trial and Wilde’s conviction.

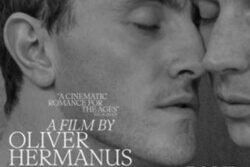

“Bosie” Douglas) in The Judas Kiss

The Judas Kiss opens with a distracting trifle, a sex scene between a bellhop and a maid in the Cadogan Hotel in London where Wilde is about to make a fateful choice: to stay and face charges or to flee. Bosie soon arrives along with Wilde’s former lover, Robbie Ross, and the action is set in motion. Bosie urges Wilde to stay and fight, while Ross begs him to leave on the hour, knowing it to be the saner course. But Wilde will not disappoint Bosie.

Act I is an old-fashioned drama of ideas and speechifying. Even when adorned with the famous Wildean wit, it comes across as heavy-handed. In part, this is because Hare has chosen to make Bosie the sole villain, amplifying his faults—self-centeredness, vanity, promiscuity, contempt—while giving him few redeeming qualities. One wonders why Wilde loves him to the point of risking his reputation and life. Robbie Ross, on the other hand, is more well-rounded, torn by his love for Wilde and his jealousy of Bosie.

The ball bounces back and forth—stay or flee, stay or flee—until the argument turns tedious. Even Wilde thinks so, demanding wine and a lobster dinner, as though what hangs in the balance—i.e. his fate—could not possibly be more important than pleasure. Only an outright breakdown on Wilde’s part when he and Ross are alone clues us in that more is going on beneath the surface than his witty posturing will allow.

Act II shifts the action to Naples, where Wilde and Bosie have reunited after Wilde’s two-year sentence has ended. Bosie’s promises to help Wilde get back on his feet have fallen flat due to a lack of money. Ross arrives on a mission from Wilde’s wife Constance to remind him of his promise to avoid all future association with Bosie on pain of financial retribution.

The play’s second half belongs to its star, Rupert Everett, as he carves out a figure of tragic greatness—sad, lost, but ultimately noble as he goes to his doom, like Jesus dragging the cross up to Golgotha. It is riveting. Wilde, now a convert to Roman Catholicism, confides to Ross that the only fault he finds with the “greatest story ever told” is that Jesus was betrayed not by a loved one like the apostle John but by Judas, a near stranger. He claims to find the dramatic possibilities of the former to be stronger and more appealing, believing himself to have succumbed to such a fate himself.

Despite Wilde’s desperate, broken state, Everett gives us the Oscar Wilde we believe we know and love—funny, outrageous, slightly ridiculous, but always morally centered as he faces his final predicament: the loss of love. Here, in fact, is the Wilde who gave us transcendent works like The Happy Prince, who sided with the poor, the lost, the neglected, and the morally wayward.

The sharp dichotomy in setting between the two acts, highlighted by their contrasting set and lighting designs, creates two very different moods. It’s as if we had set out at noon on a utilitarian scow bound for who-knows-where, only to find ourselves at sunset on a sailboat of the most beautiful, ethereal sort. It is not the death barge of a Carthaginian queen sent to her final resting place, but instead the vessel of a spiritually ennobled, though physically and emotionally bankrupt Irishman whose rashness set the course for a century of rebellion against an old taboo.

Jeffrey Round is the author of nine novels and one volume of poetry. He is also the co-founder and program coordinator of Naked Heart, Canada’s first LGBT Festival of Words.