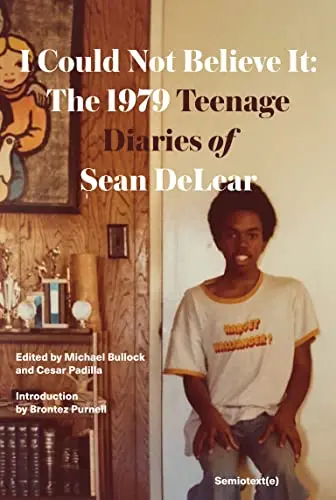

I COULD NOT BELIEVE IT

I COULD NOT BELIEVE IT

The 1979 Teenage Diaries of Sean DeLear

Edited by Michael Bullock & Cesar Padilla

Semiotext(e). 215 pages, $16.95

A HOST of accolades marks Sean DeLear’s posthumous reputation: “the Queen Mother of alternative music,” “a punk rock fairy godmother,” “a walking work of art,” “a person who single-handedly made counterculture feel viable,” AND “a fierce, fully formed faggot.” To use an expression DeLear often applied to others, he was a “bitchin’ babe.”

“He was so many things,” writes Michael Bullock, co-editor of DeLear’s teenage diary I Could Not Believe It, recently issued by Semiotext(e): “punk musician, intercontinental scenester, video vixen, dance-track vocalist, party host, heavy-metal groupie, marijuana farmer, and even Frances Bean Cobain’s babysitter.” DeLear was the lead singer of the power pop-punk band Glue, which was a vital element in the Silver Lake scene of the 1980s and ’90s. Adored for his matter-of-fact androgyny and his “lyrical and vocal tempestuousness,” he later went on to collaborate with performance-based artists, joining the European art collective Gelitin and performing as a solo cabaret artist.

DeLear was born Anthony Robertson in 1965 to evangelical Christian parents, among the first Black couples to move to Simi Valley. While the diary provides little information about his early life, we do learn that Sean and his friend David were “doing things since we were about eight or nine.” Whatever those things were, they left DeLear with an early and remarkably guilt-free outlook on sex. The diary, which DeLear began on New Year’s Day 1979, when he was fourteen, was found after he died in 2017. The entries, mostly a paragraph long, take us on a stream-of-consciousness ride into the mind of a typical teenage boy with a precociously playful curiosity about gay sex. A lot of the diary focuses on the kinds of activities we might expect of any adolescent boy: fleeting crushes, high school sports, a prize possession (a Minolta XG-7 camera), boredom with school, a paper route, trying out for a part in Bye Bye Birdie, saving money to buy a waterbed, happy expressions of surprise at how popular he is at school, posing for the big ninth-grade photo, renting a tux for the formal, picking up his copy of the yearbook. “I want everyone to sign it that is popular,” he writes. It comes as no surprise that DeLear loved music, which he listened to on 8-track cassettes. The list of his favorite artists brings us right back to the late ’70s: Donna Summer, the Village People, Sound Factory, Sister Sledge, Cheryl Lynn, Peaches and Herb, Machine, Blondie, Bonnie Pointer, Sylvester, Rick James, Led Zeppelin. His high school seems to have been a progressive one. In addition to the usual subjects, he takes classes in oceanography and photography (his favorite). Still, he finds school a bore. When his report card comes out during the fall of his freshman year, all his grades are Ds and Fs. He keeps resolving to get his act together, but at age sixteen, he drops out. Sean is also gay, and he uses the diary to explore his growing understanding of what that means. He puzzles over who is and isn’t gay in his class. He’s keen to pick up more information about homosexuality, and does so by reading The David Kopay Story and stealing copies of Blueboy, Honcho, and Mandate. But reading is not enough. He can’t wait to see “all that fat cock” in PE class. He makes forays to malls and bowling alleys, where he picks up “a wide variety of tricks.” Soon he has taken to “working the streets, just being your typical little hustler boy.” He tries on heels—“but they were not big enough so I have to go somewhere else”—and flirts with bisexuality: “So what, so I want to go to bed with a man or a women [sic]—no biggie is it?” At the end of June, he sucks his first uncut cock, then goes to his friend Lori’s house and sucks on her boobs. “My first girlfriend,” he writes. Arrested for masturbating in a public restroom, he has to attend counseling sessions. The shrink turns out to be “pretty cool.” Sean wants to be hypnotized in order “to skate better, do my schoolwork, not lie, not cuss, bowl and golf better, and not be shy around people I don’t know.” A month before his fifteenth birthday, he gets a fake ID so he can go to a gay bathhouse. Still, he worries about being busted if he gets it on with an adult. Sean’s diary shifts between a sweet, almost childlike preoccupation with the quotidian details of a high school freshman’s life and candid accounts of his sexcapades. Often, within the same paragraph, his attention is drawn to both the puerile and the prurient. At the end of the school year, for example, he wants either a Mickey Mouse watch or the book Marilyn Monroe Confidential. That summer, he makes and films a Claymation featuring Mr. Bill of SNL fame. Later, in the same entry, he wishes he “could fuck or suck some man for money.” Those kinds of quirky juxtapositions became an essential feature of his personal and professional self-presentation. In his introduction to the diary, Brontez Purnell writes: “So very little is written about the lives and the bold sexuality of young queers, and specifically young Black queers, that I also have to give regard that there is something ultimately explosive about this text.” DeLear often ended a diary entry with the expression “Oh Well.” It was a kind of offhand expression of acceptance—radical acceptance, I’d say—at simply being the “super bitchen” young person he was. He remained “super bitchen” his entire short, glittering life.