Anthony Friedkin: The Gay Essay

by Julian Cox and Eileen Myles

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and Yale Univ. Press. 144 pages, $45.

Exhibition at the de Young Museum, San Francisco,

June 14, 2014 – Jan. 11, 2015

THE WORD “DOCUMENT” is from the Latin docere, to teach, instruct, or point out. When coupled with “photography,” the idea is that the camera acquires a kind of moral authority when recording social conditions or promoting social change. Documentary photographs function as visual narratives with ramifications that extend beyond the frame. Such images perform an evidentiary function: as character studies of marginalized populations and grassroots political movements for social justice; and as rural and urban histories that depict natural or man-made disasters of displacement, homelessness, poverty, war, and trauma.

The importance of documentary photography is ever present in Anthony Friedkin’s The Gay Essay, a portfolio of photographs from the late 1960s to the early ’70s that focuses on the gay liberation era in San Francisco and Los Angeles. The photographs are on exhibit at the de Young Museum in San Francisco with a catalogue published by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and Yale University Press.

Most of Friedkin’s images articulate exquisite pain and sadness; they are representations of traumatized people some of whom seem unaware of their loss or fragility. Some photographs portray the vulnerabilities of street life and cruising; others highlight the lack of social support systems, deprivation, loneliness, and substance use. Some portraits are full of hope and imagination, such as those taken at early pride marches, but others make the viewer wonder how these people will ever find their way. There are also images of activist pioneers, such as Don Kilhefner (a founder of the Radical Faerie movement) protectively wrapping an arm around Morris Kight (a founder of LA’s Gay Liberation Front). Of Friedkin, Kight commented: “He was on fire with creativity. He saw things that other people didn’t see.”

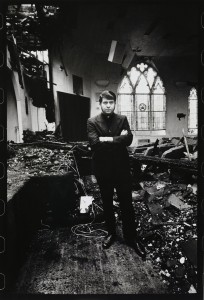

in His Burnt Down Church,

Los Angeles, 1973.

There is a powerful 1973 image of Troy Perry, founder of the Metropolitan Community Church (MCC), resolute yet devastated, surrounded by the rubble of the burned-to-the-ground LA Mother Church (Figure 1). There were three other fires at MCC churches during the first half of 1973, and in subsequent years arsonists destroyed seventeen more. The fire at the Upstairs Lounge in New Orleans, a gay bar used for MCC services, killed 32 people, including the pastor, assistant pastor, and half the congregation. Most of the New Orleans churches refused to allow memorial services, and some families refused to claim the victims’ remains. The photograph is a historic reminder of the violent opposition LGBT people faced and our courageous struggle for equality.

Friedkin’s photographs anticipate the unceasing complexities of what became known as the GLBT movement, many of which have persisted for decades, such as views about lesbian-feminist separatism, transgender inclusion or exclusion, race and class in white-dominated, middle-class organizations, and the dogmatic, ideological, internecine infighting that’s common to all political movements. The abbreviations GLBT, LGBT, and their variants came into widespread usage during the 1990s. The first reference to LGBT in the Oxford English Dictionary is 1992 on GayNet, an e-mail listserv. The use of initials was more for expediency than political inclusivity and has always been contentious. Should the “L” precede the “G”? Should the “T” for transgender be included? Over the decades, other contenders have included an “I” for intersex, “Q” for queer and/or questioning, “A” for allies and/or asexual, and a case is now being made for adding “O” for other.

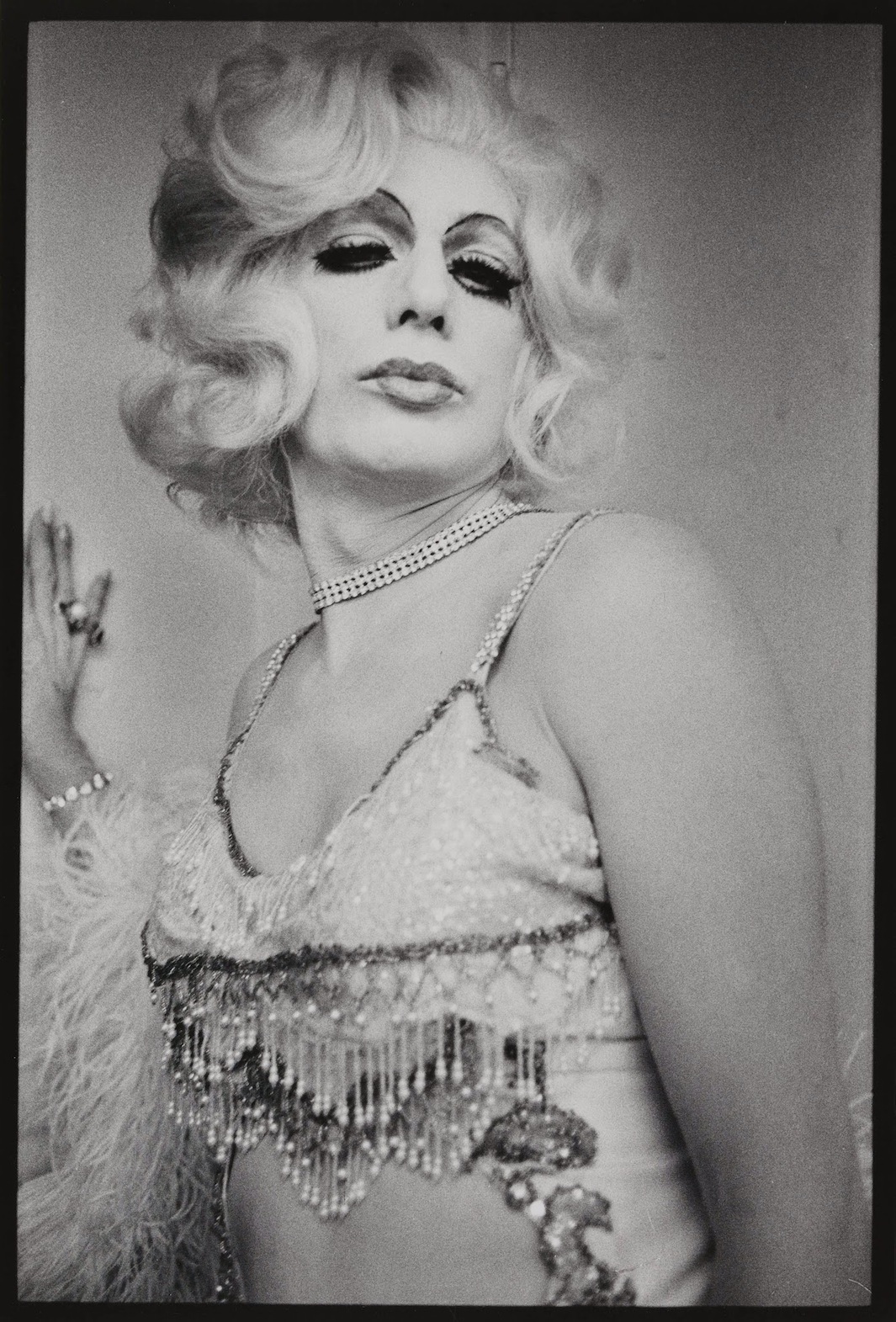

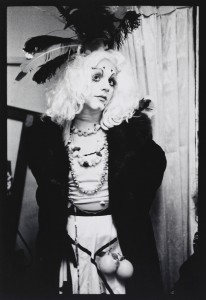

Nearly a third of the images in both the book and exhibition refer to gender issues in some manner, not excluding drag queens, female impersonators, performers, and a detail from Jean Harlow, Drag Queen Ball (which is the catalogue cover photograph: see Figure 2). Friedkin believed that images of transgender people are integral to GLBT history. In 1972, he went to San Francisco

specifically to photograph the gender-bending Cockettes, an experimental theater troupe. Among the images taken on that visit is one of performer Pristine Condition wearing an extra-body scrotum amulet (Figure 3). The transgender photographs are a vestige of an era of imprecise terminology—androgyny, cross- dressing, drag, gender-bending, transvestite, transsexual—and bogus theories from medicine and popular culture. The question of whether transgenderism is subversive or misogynistic, a challenge to gender norms or a parody of women, is the elephant in the

San Francisco, 1972.

room.

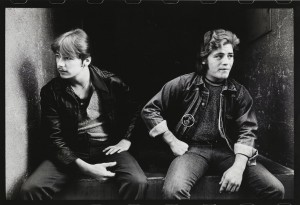

Perhaps as an unwitting cultural provocateur, Friedkin focused on the seedier side of gay life in Hollywood in his male hustler portraits. Hustling was increasingly prevalent during the 1960s, a subset of the gay male subculture that inverted commercial gay male representations and their idealization of attractiveness with stereotypical hypermasculinity, street toughness, and pseudo-criminality. Friedkin’s portraits, in contrast, capture the post-traumatic stress disorder of their desensitized faces, ravaged by years of trying to survive on Hollywood’s main thoroughfares (Figure 4).

Documentary photographers have always served as change agents, provocateurs, and storytellers, often mak-ing images of people who prefer to remain unobserved and anonymous. The titles of many photograph and art books reference the secretive pre-Stonewall status of gay

people (e.g., Hide/Seek; Hidden History; A Hidden Love; Becoming Visible; and The Invisibles). Clearly, social change was never far from the thinking of Friedkin, who’s quoted as saying: “The idea is that you celebrate humanity for its good things, but you also identify things that need to be reevaluated and changed.” And: “I thought it was horrible the way gay people were treated by our society. … It made me angry. … They express themselves in a free way with love and affection. So you know, I wanted to try to record that. Just out of the dignity I thought they deserved that many people wouldn’t give them.”

All figures copyright © 2014 by Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and Yale University Press.

Steven F. Dansky has been an activist, writer, and photographer for more than fifty years. He is the founder of OUTSpoken: Oral History from LGBTQ Pioneers.