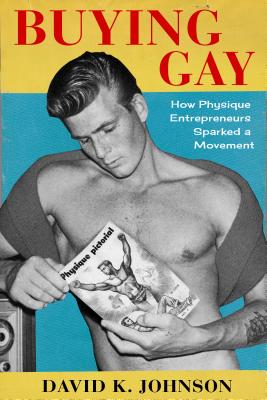

Buying Gay: How Physique Entrepreneurs Sparked a Movement

Buying Gay: How Physique Entrepreneurs Sparked a Movement

by David K. Johnson

Columbia University Press

320 pages, $32.

THE “PHYSIQUE” photographers and periodicals of the 1950s and ’60s were not just a byproduct of the Homophile movement of this era, but were a catalyst for it. This in a nutshell is the thesis of a new book by David K. Johnson titled Buying Gay: How Physique Entrepreneurs Sparked a Movement. These entrepreneurs, argues Johnson, supported the movement financially and fought the legal battles that got it going.

This history has gone largely untold. LGBT historians tended to be dismissive of the physique pioneers, and some were hostile, “seeing in them only evidence of racism, self-loathing, or the closet,” in Johnson’s words.

Bob Mizer and Physique Pictorial

The story begins in Los Angeles with Bob Mizer (1922–1991) and his Athletic Model Guild (AMG). As a teenager, Mizer was part of the Pershing Square gay subculture, which included, according to Hart Crane, “little fairies who can quote Rimbaud before they are eighteen.” In 1940, when Mizer was in fact eighteen, he encountered antigay bigotry, which inspired him to write in his diary: “My aim in life will be to create tolerance among mankind and especially to vindicate the decent, spiritual Urning.” His use of the German word Urning shows that he was familiar with the writings of Carl Heinrich Ulrichs (1825–1895), often considered the grandfather of gay liberation; he was therefore ahead of most homophile leaders, who were unaware of the 19th-century German homosexual rights movement.

When Mizer placed a personal ad in Strength & Health (April 1945), the leading “physical culture” magazine, he received over 300 letters from fellow readers. He grasped the potency of, and later profited from, “the desire of men who enjoyed physique photography to connect with each other.” After an apprenticeship with Frederick Kovert, an early physique photographer, Mizer bought equipment and began to frequent Muscle Beach and bodybuilding competitions to find models, who were happy to pose in exchange for free photos of themselves. Mizer called his business the Athletic Model Guild (AMG), and in 1946 he began advertising in Strength & Health.

As his business developed, so did his legal troubles. Postal inspectors in 1945 searched his home, found “dirty pictures,” and took him in for questioning. Somehow he escaped arrest. But in 1947 he faced more serious charges: photographing teenage models in the nude and contributing to the delinquency of a minor. Showing no remorse for his activities and admitting he was homosexual, Mizer was sentenced to six months in a California work farm. The experience steeled his will and led to a lifelong fight for civil liberties and against censorship.

Mizer was successful in selling his prints to individual customers, and his photographs began to appear in ostensibly straight physical culture magazines like Strength & Health. He branched out into the mail order business with the help of his brother and his mother, a seamstress who made custom posing briefs.

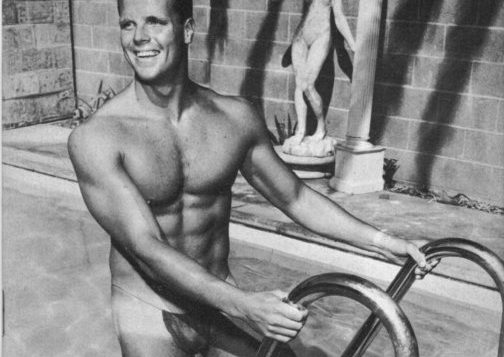

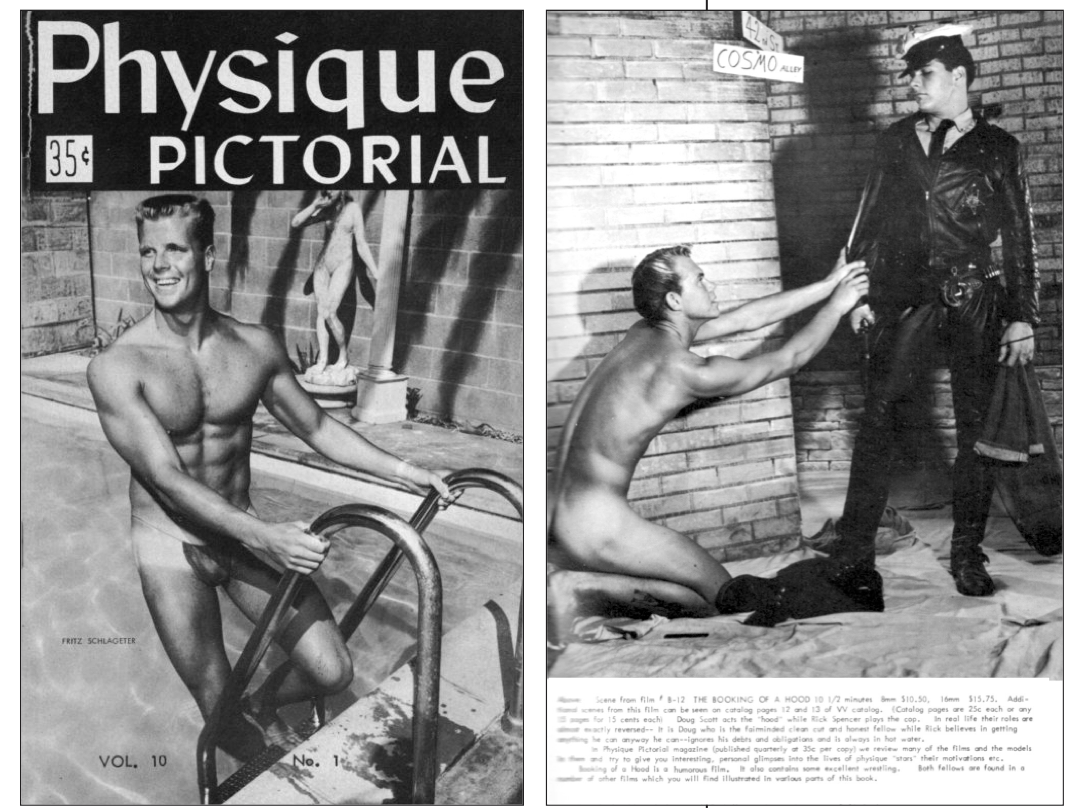

In 1951, he started Physique Pictorial (PP), a quarterly magazine that continued sporadically all the way to 1991. I have almost a complete run in my personal collection. PP was unlike anything that came before. There were photos of bodybuilders, but also of more natural, boyish types. Mizer added copious comments on the evils of censorship, the risks of pen-pal correspondence, the selection of photographic equipment, and the personalities of the models, some of whom had engaged in antisocial behavior. (In Volume 18 #1 is a photo of a young man in a shower with the words “Portrait of a Killer,” as this is Paul Ferguson who, with his brother, beat to death the silent movie star Ramon Navarro.)

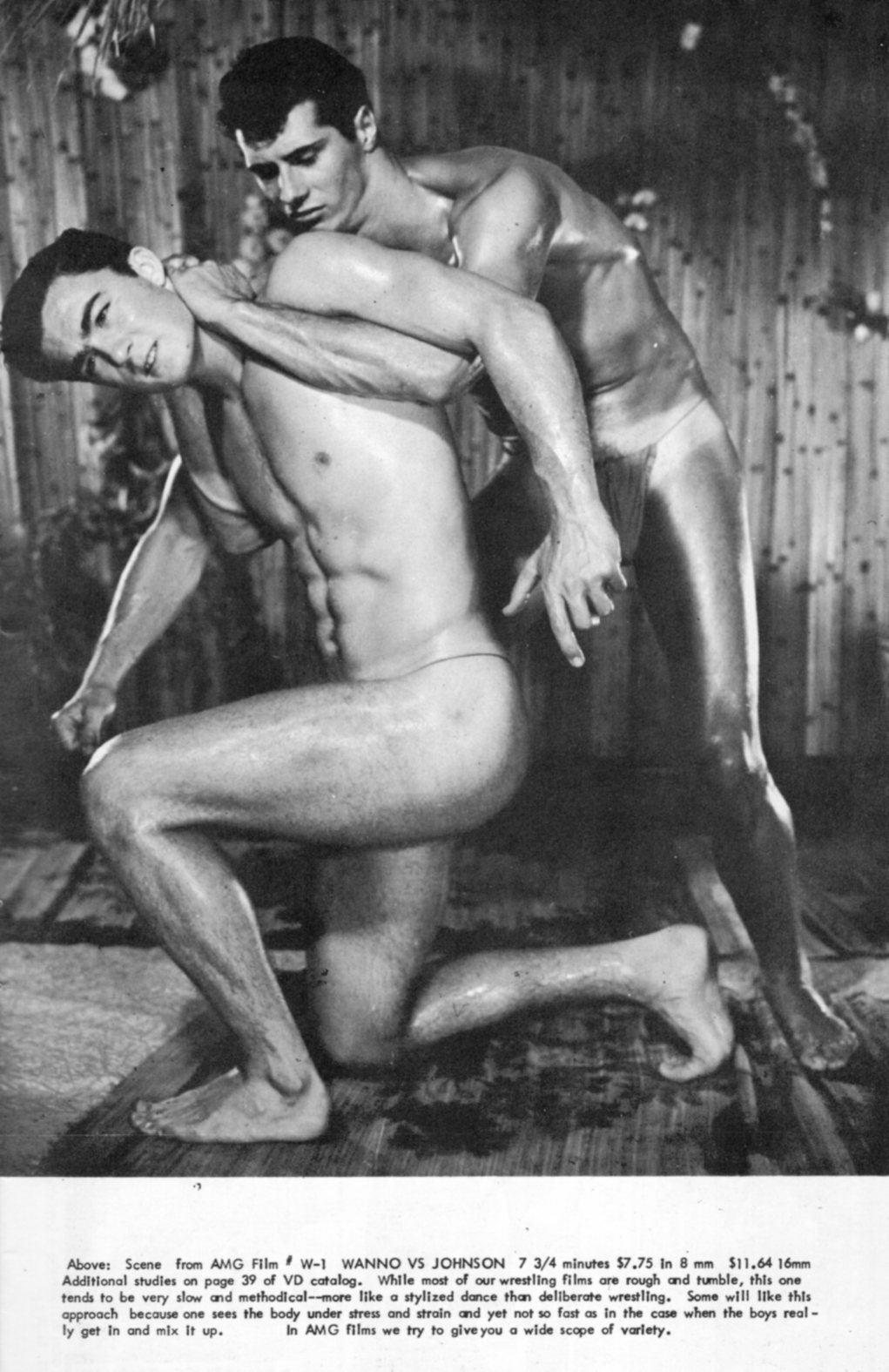

In the 1960s Mizer began making 8mm. films, which fell into three main categories: solo posing; stories involving convicts, cops, hoodlums, princes, gladiators, etc.; and wrestling. I can speak from experience here, as I bought an 8mm projector and began buying the AMG films. If a film failed to “inspire,” you could mail it back to AMG for 75 percent credit on your next purchase. Over the years, with this leeway, I watched hundreds of films, permanently acquiring those that I really liked. On one occasion I had a showing in my New York City apartment for about ten gay liberationists, including Italy’s leading gay activist, Massimo Consoli. About half were entranced and half were bored, wondering when something was going to happen. These films have a quasi-innocent eroticism; they are definitely not hard-core porn.

In the mid-’70s I traveled to L.A. to visit pioneer gay activists W. Dorr Legg and Jim Kepner. While there, I made a pilgrimage to the AMG headquarters, which by then was a compound of several buildings, including a swimming pool that was used in many films. Near the pool I had a one-hour talk with a congenial Bob Mizer. I gave him a copy of the book I co-authored with David Thorstad, The Early Homosexual Rights Movement (1864-1935) (1974), and found that he knew a lot about the early movement, especially the trilingual monthly Swiss periodical, Der Kreis / Le Cercle / The Circle, which preceded AMG in publishing homoerotic photos. Mizer told me that his best models came from the U.S. military, especially the Marine Corps and the Navy. Not only did these young men have good physiques from military service, but they also had discipline—they knew how to follow orders, whether in posing or acting in a film.

Greenberg and Grecian Guild

Gay book publishing also supported the early homophile movement. In 1949 Greenberg Publishers, founded in 1931, published Nial Kent’s The Divided Path, which had an ending that for the time was controversial. Previously gay novels had to end tragically: gay men had to die from suicide, murder, or accident. The Divided Path ends ambiguously, with the slight possibility of a happy ending. As a publicity gimmick, the Greenberg editor, Brandt Aymar, launched a contest with cash prizes for the best essays on whether their novels should end “on a note of hope.” The contest was a resounding success, with 500 entries, almost all of which wanted a happy ending and more such books. The Divided Path, with virtually no mainstream publicity, became a minor bestseller, with 130,000 copies sold by 1955.

In 1951 Greenberg published The Homosexual in America, by “Donald Webster Cory” (pseudonym for Edward Sagarin), an insider’s view of the gay community. They publicized the book heavily, and it sold out in ten days. Letters came in from readers all over the world who expressed their gratitude for a book that spoke for them. I was in my early teens when I read it in a small town Carnegie library, afraid to check it out. I realized that I wasn’t alone but wasn’t entirely consoled by Cory’s model, which held that homosexuals represent a discrete minority, like Jews or Negroes, that ought to be tolerated.

Later that year, a U.S. attorney in Maryland charged both Greenberg and editor Aymar with publishingobscene novels. Although none of the Greenberg novels contained explicit descriptions of sex, the mere suggestion of homosexual behavior was considered obscene. Legal battles continued for years, Greenberg paid a fine of $3,000 to avoid going to prison, and the Greenberg novels were pulled from circulation.

In the midst of these legal troubles, Aymar and Cory founded the Cory Book Service (CBS), a mail-order business selling books of interest to a gay audience. CBS was successful and became “an integral part of the burgeoning homophile movement.” But Cory was con- flicted over his own sexuality and embittered over what he thought were betrayals by ONE, Inc. and the Mattachine Society, the two leading gay organizations in California. So, in 1954 he sold CBS to a heterosexual housewife, who ran it competently and profitably. Other book sellers were founded, including Dorian Book Service, founded by Hal Call, head of the San Francisco Mattachine. Mailing lists were exchanged among book services, other commercial interests, and homophile organizations.

The premier physique magazine that followed Physique Pictorial was Grecian Guild, founded by Randolph Benson and John Bullock, two young men who met while students at the University of Virginia in the early 1950s. Forming a life partnership that endured for sixty years, Benson and Bullock established a modest photography studio in Charlottesville. Interested in boy-next-door rather than bodybuilder types, they recruited models from their fellow students. Bullock himself took up bodybuilding and appeared both behind and in front of the camera.

The first issue of Grecian Guild, in August 1955, “offered membership in a fraternal order of men dedicated to the appreciation of the beauty of the male body.” Benson and Bullock envisioned a fellowship that might include annual conventions, summer camps, gatherings for physique artists and photographers—a vision of male camaraderie: “a place of our own where contests and physique shows can be held and where we can sun and swim and pursue the ways of health and happiness.”

Grecian Guild was a great success financially. At its peak, Benson and Bullock made more in a week than a college professor made in a year. The Grecian Guild fellowship also caught on and even attracted men of the cloth. Randolph Benson proudly described himself as an Episcopalian, John Bullock as a Presbyterian. A 33-year-old Episcopal priest appeared in two photographs—one in his clerical collar and the other in a posing strap. A Congregationalist minister, Robert Wood, was a charter Grecian Guild member who also stripped down. Buying Gay has two photos of the sturdy Rev. Wood. In one he’s wearing his collar and in the other he’s standing in posing brief on a Provincetown beach holding a young man on his shoulders. Wood later wrote a book, Christ and the Homosexual (1960), in which he tried to reconcile being gay with his Christian faith.

In the late ’50s, the postal authorities caused trouble for Grecian Guild and its newsstand distributor. Benson and Bullock sold the magazine to Lynn Womack, and they retreated into the closet. Benson had a distinguished career as a professor of sociology at Roanoke College, and Bullock became a popular art teacher. Both of them died in their eighties, within two weeks of each other. They are buried in adjacent lots in an Episcopal cemetery in Charlottesville.

Heroes in the Post Office Wars

A chapter of Buying Gay titled “I Want a Pen Pal!” tells a grim story, that of the vicious persecution of gay men by Postmaster General Arthur Summerfield. Many gay men in the ’50s, especially those living in the country or small towns, were isolated and longed for companionship. Mail correspondence satisfied part of that need. Over the years, gay men using coded language found each other through such publications. The campiest of the small physique magazines was called Vim. In 1959 its new editor, Jack Zuideveld, a married man with two children, decided to make Vim more openly gay. In addition to photos of male bodies, he included news items and articles, both serious and light-hearted. It was Zuideveld’s wife Nirvana who got the idea for a pen-pal club. The Adonis Male Club made its debut in the June 1959 issue, and it soon had a membership of 750.

Alas, Postmaster General Arthur Summerfield had pledged “a war to the finish” against what he considered purveyors of obscenity—and any suggestion of homosexuality qualified as obscene. Under Summerfield’s instigation, the U.S. government indicted over fifty members of the Adonis Male Club on charges of conspiracy to send obscene materials through the mail. The Post Office infiltrated mailing lists and visited gay men around the country, forcing them to turn over evidence, inform on others, and sign confessions. Several club members committed suicide, and several more attempted it. The Post Office began to pay “educational visits” to employers of men who were in gay pen-pal clubs or who received homoerotic material. They especially targeted teachers, whose lives and careers were often ruined even if they weren’t convicted of any criminal charges.

The federal trial involving the Adonis Male Club began in Chicago in January 1962. After a long and messy four-week trial, all of the ten defendants who had not already pled guilty were found guilty and placed on probation. Both Jack and Nirvana Zuideveld were sentenced to a year in federal prison.

With the new administration of John F. Kennedy, Summerfield was out as Postmaster General, replaced by the somewhat more enlightened Larry O’Brien. The New Republic in August 1965 printed an exposé of the Post Office’s extralegal tactics, including its “educational visits” to employers. O’Brien ordered the practice stopped. When the Department of Justice ordered a stop to prosecutions of private correspondents for obscenity, the Post Office largely ceased its campaign against consumers, although it continued to harass the physique magazines.

The Post Office found its nemesis in Lynn Womack, a “Caucasian albino” who grew up in Minnesota. After a checkered career (marriages, children, coming out at age 27, a doctorate from Johns Hopkins, employment in and outside of academia, various business ventures), Womack was seeking to invest a tidy sum that he had acquired through a rather dodgy business venture. From Randolph Benson of Grecian Guild he bought TRIM magazine, and found himself faced with a problem affecting all of the physique magazines: newsstand distribution. Since the American News Company had folded in 1957 under harassment by the Post Office, smaller distributors shied away from physique magazines. Tough as well as brilliant, Womack solved the problem by forming his own distribution network, declaring to Benson: “We will never again be at the mercy of a distributor, agent, newsstand owner, or anyone else.”

Womack began printing Grecian Guild Pictorial, and later bought the magazine. He also bought the physique magazines MANual and Fizeek. He assembled a stable of physique photographers, encouraging them to relocate near his Capitol Hill residence in Washington and offering legal defense if they got into trouble with the postal authorities. He put together a legal lending library of bulletins, briefs, and other materials related to homosexuality and censorship. According to Womack, his collection was “in constant use by attorneys from all over the country.”

rough and tumble, this one tends to be very slow and

methodical—more like a stylized dance…”

In 1960 Womack and two of his photographers were arrested for placing nude photos in the mail. Magazines were seized and Womack’s 40,000-name mailing list was confiscated.

Judge Holtzoff regarded the new charges as a betrayal of Womack’s agreement to cease publishing, revoked his bond, and ordered him to report to jail to serve his sentence, which was now two to four years in prison. However, Womack, who had studied psychology, managed to trick psychiatrists, who assumed that homosexuals were mentally ill, into giving him a diagnosis that led him to be confined in St. Elizabeth’s Hospital—the facility in which Ezra Pound had been confined after World War II. Womack continued to run his businesses from St. Elizabeth’s, which he described as “very pleasant. I had a private room, TV, typewriter.”

Although every court in Womack’s obscenity cases had ruled against him, he carried his appeal to the Supreme Court in the case of Manual v. Day; and he won. By a six to one decision, the court ruled that the Guild Press publications were not obscene because they were not “patently offensive.” Womack reveled in his newfound freedom, telling one of his photographers: “I did not fight, spend money, go to jail, come to Saint Elizabeth’s to spend even one moment of my life living in fear of anything.”

Womack went on to acquire more physique magazine and build a gay empire, which included the Guild Book Service, a clothing business, and a correspondence club. In 1965 U.S. Customs officials attempted to stop Womack from importing Danish nudist magazines like Hellenic Sun and Youth at Play. Womack fought them all the way to the Supreme Court, and again he won. The postal authorities would continue to harass him after that, but by 1970 he had the support of movement leaders and the newly formed Gay Activists Alliance.

Another concern that tangled with the U.S. Post Office was Directory Services, Inc. (DSI), founded in 1963 by Lloyd Spinar and Conrad Germain, two young business school graduates from small towns in the Dakotas. Although they had no products to sell themselves, they realized they could sell information. Initially DSI provided directories of gay bars, physique photographers, and so on. This enterprise was so successful that before long DSI was supplying merchandise—books, records, jewelry, clothing, home furnishings, and greeting cards—and offering a discreet photo finishing service. They started a pen-pal club and began producing their own physique magazines. Entering into a cozy relationship with the mob, which controlled erotic bookstores and distribution, they were making millions.

Unfortunately, the Post Office meanies, emboldened by some ambiguous lower court decisions, resumed its harassment of gay men and gay businesses. Pen-pal members were arrested for sending obscene materials through the mail; magazines and equipment were confiscated; Spinar and Germain were arrested on several charges of obscenity. When they refused a deal that would have forced them to cease publishing, they went to trial in federal court. The year was 1967, and times had changed. They had support from the community, including local newspapers. The pair must also have had charm, as they seem to have converted their next-door neighbor, Abigail Van Buren (the “Dear Abby” columnist), from a homophobe to an ally who attended their victory party. Experts testified in their defense, including Ward Pomeroy, co-author of the Kinsey reports. The judge, Earl Larson, a founder of the Minnesota Civil Liberties Union, found Spinar and Germain not guilty on all counts.

In a way, this landmark case for gay rights started the DSI’s downfall. Once homoerotic materials could be freely sold, competitors arose on all sides. Magazines featured not only full frontal nudity but overtly sexual images. Spinar and Germain moved to L.A. and began spending lavishly. Their relationship fell apart. Their business practices became questionable, and the quality of their services deteriorated. Eventually, Germain was convicted of mail fraud, spent time in federal prison, and was released on condition that he not engage in mail order.

David Johnson’s history essentially ends here. His final chapter, “The Physique Legacy,” discusses some post-Stonewall events and concludes with the statement: “The business of producing and disseminating homoerotic images helped forge a movement.” Case well made.