Coming Together: The Cinematic Elaboration of Gay Male Life, 1945–1979

Coming Together: The Cinematic Elaboration of Gay Male Life, 1945–1979

by Ryan Powell

U. of Chicago Press. 275 pages, $35.

I LIKE to consider myself moderately well-versed in gay cinema, but I learned some surprising things from Ryan Powell’s Coming Together: The Cinematic Elaboration of Gay Male Life, 1945–1979. For example, who knew that more than 300 films about gay men were made during the 35-year period Powell examines, which spans the end of World War II to the beginning of the AIDS crisis? Most of these films were made by gay men for an audience of gay men. That number astonishingly climbs into the thousands if mail-order physique films are included in the tally.

I was also surprised by the extent to which these films brought gay men together socially. Modern technology now allows us to watch films alone in almost any location, but that was not the case in the mid-20th century. Gay men had to gather in public places, risking harassment or arrest, in order to see themselves portrayed on the big screen. Kenneth Anger’s Fireworks, one of the first and most important gay films of the early postwar era, ran for months at West Hollywood’s Coronet Cinema in 1947, where it drew an enthusiastic audience. Other cinemas in large cities followed suit and began to show underground films by Anger and others.

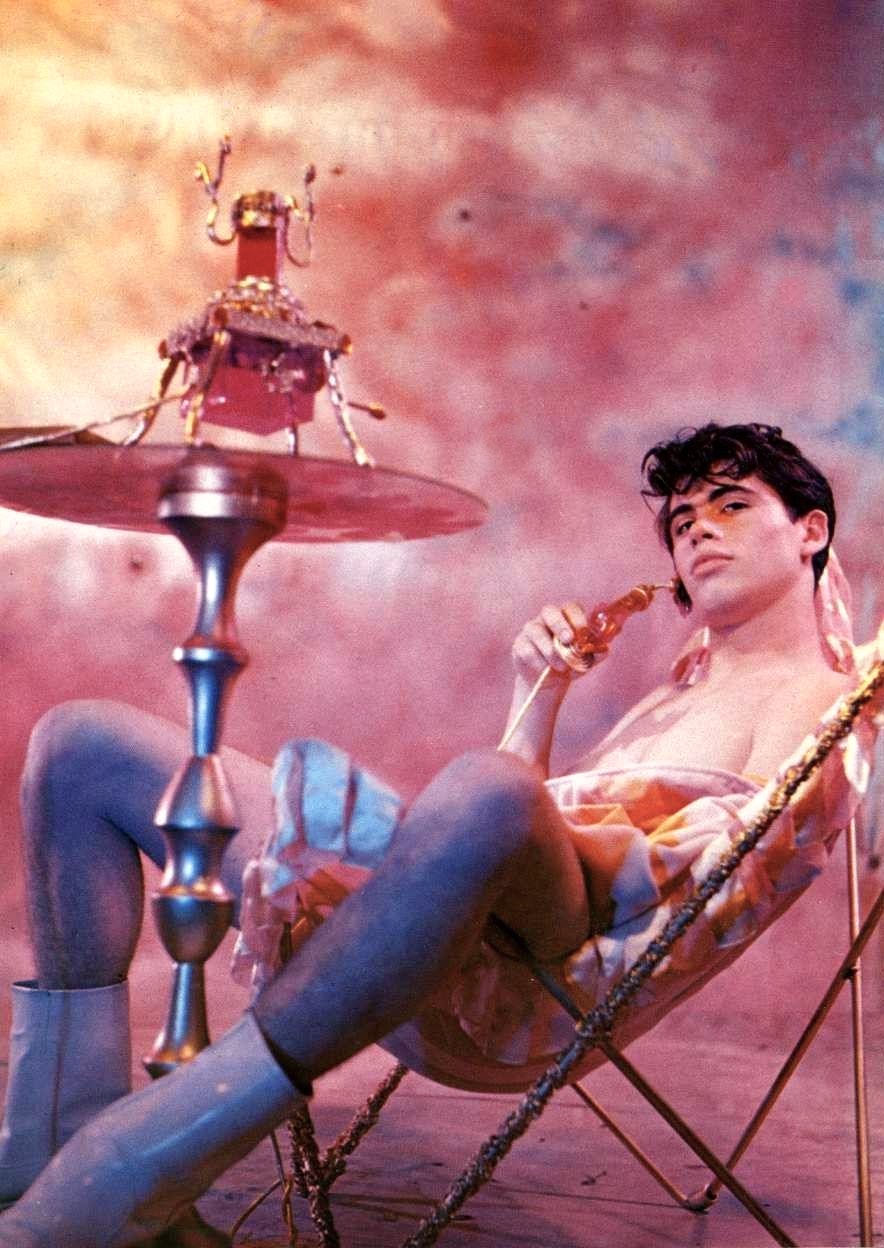

Among the many classic gay films that Powell analyzes are Pink Narcissus, The Boys in the Band, Boys in the Sand, and Joe Gage’s epic hardcore porno Kansas City Trucking. But Powell also examines many other, less well-known films like those made in the 1960s by a Los Angeles gay men’s social group called the Gay Girls’ Riding Club. They produced several parodies of mainstream Hollywood hits, including What Really Happened to Baby Jane? and Spy on the Fly, a James Bond spoof featuring secret agent 0069 donning drag to deliver top secret information. Learning about these more obscure films was one of the pleasures of Coming Together. Who wouldn’t want to see 1972’s American Cream, a political porn film that Powell describes as “part hard-core, part Brechtian social drama, and part GI/military drag show,” and includes images of Richard Nixon and the Washington Monument intercut with scenes of an oppressed office worker sodomizing his boss? Or perhaps The Destroying Angel (1976) might be more to your liking. The plot involves a Catholic priest whose repressed homosexuality creates an evil doppelganger. Trouble (and lots of sex) ensues. Powell also looks at the work of Civil Rights activist turned director Pat Rocco. In the 1960s, Rocco created documentaries on gay life like Meat Market Arrest (about the arrest of a male go-go dancer at a gay bar) and filmed interviews with Troy Perry, founder of the Metropolitan Community Church, and other early gay rights activists. Of course, Rocco also made racier fare like The Luckiest Cat in Town, a physique film in which four different men pose nude with a cat. Both Rocco’s serious and sexy films were often shown together as one program, and his work inspired a fan club, the Society of Pat Rocco Enlightened Enthusiasts, or spree. Members of spree would gather to watch movies but also socialized at pool parties and put on musical theater productions. Reading Coming Together requires a modest tolerance for academic jargon, but Powell, an assistant professor of cinema and media studies at Indiana University, uses it in a mostly illuminating way. For example, here he explains how viewers might feel after watching Bob Mizer’s Athletic Model Guild films, which were made cheaply in and around Mizer’s California home. Using low-budget props and homemade set pieces, Mizer transformed his backyard into a Roman slave market, a jail for handsome sailors, or other fantasy settings. With a few fake boulders, his roof might become a desert for scantily-clad cowboys and Indians. Powell writes: “As the quasi-visible spaces of the backyard and the rooftop, for example, become discernable sites for the erotic showcasing of young men, the viewer is invited to imagine real American homes repurposed as living fantasy-scapes of endlessly renewable homoerotic pleasure.” In other words, viewers realized that if Mizer could have nearly-nude bodybuilders dressed like gladiators in his house, then perhaps they too could live out their own gay fantasies at home. Ultimately, this is Powell’s unifying theme: the way these films both reflected gay life at the time but also inspired gay men to explore new ways of living. Gladiators aside, Powell argues that simply seeing the most basic scenes of other gay men living their lives helped gay viewers imagine richer lives. “What if I could fall in love and wander around the entire city with my lover, feeling completely at ease in the absence of violence or sanction? What if there were a guy who likes the same clothes as me and might also think I’m hot because of it? What if the businessman in this empty subway car with me would enjoy having sex, right here, right now?” It’s a concern that still feels relevant today, particularly given the current political climate in the U.S. For Powell, even hardcore porn movies helped show viewers the emotional truth of gay male life. He argues that these films, with their improbable plots that always lead to sex and quite often to group orgies, reflect on some level the coming-out experience. “Gay hard-core’s plenitude of exciting, unlikely events echoes for male-desiring men the powerful experience that marks so many of our histories; the learned knowledge that a desire so many of us were told and still are told is impossible to actualize without punishment can in fact be actualized, lived, felt and expressed.” Through observations like these, Coming Together sheds light on the important role gay film has played in our history and emotional lives.

Peter Muise, who writes about New England folklore and legends, is the author ofLegends and Lore of the South Shore.