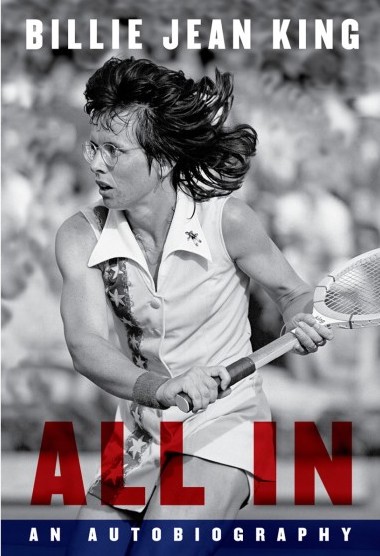

ALL IN

ALL IN

An Autobiography

by Billie Jean King, with Johnette Howard and Maryanne Vollers

Knopf. 496 pages, $30.

AS A YOUNG GIRL in the early 1950s, Billie Jean King had a terrible epiphany. Her parents had taken her and her brother to a Pacific Coast baseball game between the Los Angeles Angels and the Hollywood Stars. Surveying the players on the field, she felt a visceral wave of disappointment: “I was a girl who loved to play ball and compete. I was as good at it as any boy my age. Now I had smacked into a wall; it was the first time I realized that no matter how good I was, my life would be limited because I was female.” Unless she did something about it, that is.

Thirty-nine Grand Slam tennis titles later (in both singles and doubles), that wall had been taken down with one well-placed shot after another. King wasn’t just out for herself, though. In 1970, when haughty misogynists of the tennis establishment insisted that no one would pay to watch women play tennis, King persuaded eight other top female players to commit to a separate women’s professional tour. With her innate sense of fairness and a champion’s fighting spirit, she brought the women’s movement to women’s sports.

Born in 1943 in Long Beach, California, Billie Jean Moffitt came of age with the modern game of tennis. She was introduced to the sport by a childhood friend, took free public lessons, and quickly began beating older, more experienced opponents. She was already a Wimbledon women’s doubles champion when she enrolled at L.A. State College (now Cal State LA). In her sophomore year, she met a handsome freshman named Larry King whose squeaky-clean background was similar to her own. It wasn’t long before she left college to concentrate on tennis, and the couple got married. Larry went on to earn a law degree and become an entrepreneur and tennis promoter. In All In, Billie Jean lauds his progressive views on women’s rights and gives him credit for his role in establishing the women’s pro tennis circuit.

King treads carefully when writing about her parents, a fireman and homemaker who at times took on extra work to make ends meet. They seem to have been decent people who tried their best to keep up with their wildly talented and energetic daughter. Given the sexist tenor of the times, they might have refused to drive her to junior tournaments and talked up cheerleading instead. They might have thrown their support solely behind her younger brother Randy, who grew up to be a professional baseball pitcher. But the way King tells it, they backed their children equally and drove both of them all over Southern California to compete in their chosen sports.

Still, King internalized her parents’ prejudice against homosexuality. She struggled for years with her weight and with her sexual identity. Periodically in the book, she pauses to admit how much she suffered behind the scenes. It was only in middle age that King, now 77, began to overcome the feelings of self-doubt and inadequacy that had long prevented her from fully accepting herself. Interestingly, it was while in treatment for her eating disorder at a facility catering to girls and young women that she found her footing at last.

In the early 1970s, King had the misfortune to fall for an L.A. hairstylist named Marilyn Barnett. She coaxed the tennis champion—whose fame had soared after her victory over Bobby Riggs in the “Battle of the Sexes”—into writing letters to her from the road, letters that she would later use as blackmail material. She moved into the Kings’ Malibu beach house and refused to leave when Billie Jean asked her to, years after their love affair had ended. Barnett twice attempted suicide while living at the beach house and ended up badly crippled after jumping off a high deck. King and her business manager then decided to sell the house out from under Barnett. When the business manager offered the intransigent squatter a share of the proceeds if she would just leave—and return the letters—things got uglier. Barnett claimed she’d found more letters and wanted more money. She then sued King in a much-publicized palimony case in 1981.

In the early 1970s, King had the misfortune to fall for an L.A. hairstylist named Marilyn Barnett. She coaxed the tennis champion—whose fame had soared after her victory over Bobby Riggs in the “Battle of the Sexes”—into writing letters to her from the road, letters that she would later use as blackmail material. She moved into the Kings’ Malibu beach house and refused to leave when Billie Jean asked her to, years after their love affair had ended. Barnett twice attempted suicide while living at the beach house and ended up badly crippled after jumping off a high deck. King and her business manager then decided to sell the house out from under Barnett. When the business manager offered the intransigent squatter a share of the proceeds if she would just leave—and return the letters—things got uglier. Barnett claimed she’d found more letters and wanted more money. She then sued King in a much-publicized palimony case in 1981.

By now King had a new lover, Ilana Kloss, a younger tennis player from South Africa, whose career was imperiled along with King’s own. Obeying one of her advisers, King dispatched Kloss (who is now King’s wife) to her home country while she dealt with the firestorm. Her sponsorships vanished just as she had feared, but she still had public support—and she prevailed in the lawsuit. The conniving Barnett was a pathetic rather than sympathetic character, and King’s partial truths and outright fibs about her lesbianism and her marriage to Larry King satisfied fans content to watch her play tennis without peeking through her blinds.

Although King would have you believe she is a great champion for social justice, she’s closer to Booker T. Washington than to Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Like Washington, a master fundraiser and consummate people pleaser, King has always played to the crowd and kept an eye on the bottom line. In All In, it’s a relief when she sets aside the platitudes and dishes some dirt, however mildly. She recalls, for instance, that Arthur Ashe opposed the creation of the women’s tour. The sexist clichés he spouted to the press are cringe-worthy. As for Martina Navratilova, we learn that the ex-Czech dumped Billie Jean as her doubles partner—after they won the U.S. Open!—without bothering to tell her.

Hardly a tell-all, All In nonetheless tells more about King than she may realize. Case in point: She praises Renée Richards, the trans tennis player who made headlines in the mid-1970s, and earnestly testifies: “I was convinced that Renée was a woman.” She was so convinced that she asked Richards to play women’s doubles with her. In the midst of a semifinal match, Richards was staggeringly sick with the flu. King urged her to keep playing no matter what. During a changeover, King turned to the audience and proclaimed to much laughter: “This is the last time I’m ever playing with a Jewish American princess!” Her Borscht Belt line might not have been such a hit if Richards had fainted and been carried off the court, but “she straggled back to her feet, we won the match and, thanks to her determination, we went on to win the tournament.” It’s this kind of sunny, obtuse optimism that defines King and makes All In both a pleasure and an annoyance to read. I thoroughly enjoyed it.

Hilary Holladay is the author of The Power of Adrienne Rich: A Biography(2020).