IT WAS A NEW PROBLEM for which property developers, ever eager to pocket a buck, found the perfect solution. In the 1870s and ’80s, a disturbing species began to invade Manhattan: undomesticated young men longing to live free of their parents, but a little short of the ready to do so. They were painters and poets starving for their art; they were twenty-somethings just entering their professions, with good prospects but meager wages; they were scions of great wealth waiting for Daddy to die. Untethered and randy, the men were looking for somewhere to live that was stylish, cheap and convenient to all the sensual pleasures the metropolis had to offer. Cue the rise of the bachelor apartment building.

Building for bachelors offered several significant opportunities for cost-cutting. Since the tenants would take their meals at restaurants or clubs, there was no call for a proliferation of kitchens. Single men might even be amenable to communal toilets or shared showers. No nurseries, no live-in nannies or housemaids, no visiting in-laws to accommodate. All that the young gentlemen demanded was a thin veneer of New York sophistication—and a discreet doorman trained to avert his eyes from folly of all kinds.

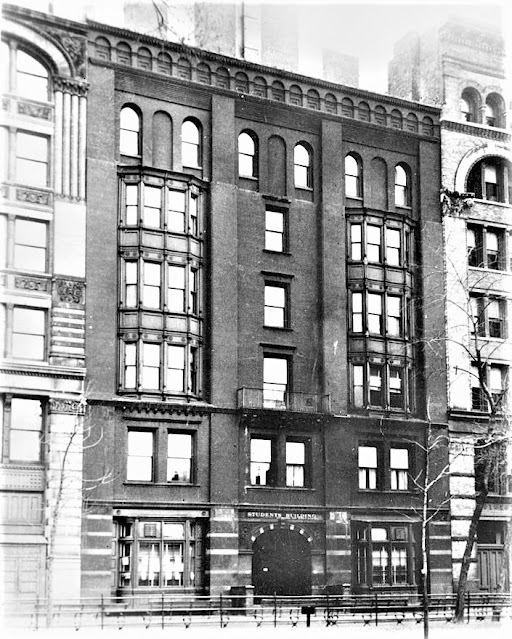

The first of these men-only apartment buildings was erected at 79-80 Washington Square East. Called The Benedick in honor of the marriage-averse character in Much Ado About Nothing, the building was intended as studios and residences for bachelor artists. To design it, the developer turned to the forerunner of the company that would become the iconic architectural firm of the Gilded Age. At the time that McKim, Mead & Bigelow took on the commission for designing The Benedick, the firm enjoyed a sterling reputation. However, the partnership soon imploded due to a double homosexual scandal. In 1874, Charles McKim married Annie Bigelow, his partner’s sister. But the marriage was not a success, and the couple separated after only a few years, Annie decamping for Newport with their daughter and a live-in companion named Rose Wagner. In the messy custody dispute that followed, Annie alleged that Charles engaged in “unnatural acts against the bounds of Christian behavior,” behaving in ways “repugnant to and in violation of the marriage contract.” Rumors suggested that not only did Charles prefer men, but it was Rose Wagner who had broken up the marriage, Annie and Rose being lesbian lovers. Forced to side either with his partner or his sister, William Bigelow chose to leave the firm. He was replaced by Stanford White—and the venerable firm of McKim, Mead & White was born.

The Benedick opened its doors in the autumn of 1879. It offered 33 apartments for unmarried men and included on the top floor four artists’ studios available for rent, studios that were accessible via that sine qua non of New York sophistication: an elevator (which would, the tenants were assured, run day and night). In residence in the building’s basement was a custodian who would provide maintenance service and furnish the men with breakfast. Also provided were maid and bootblack services. Some of the cheaper apartments lacked bathroom plumbing, however—not even the common amenity of a sink in the room—“for the sake of keeping out sewer gas.” (Before the innovation of the S-trap for plumbing, sewer gas could back up into people’s homes.)

From the outset, The Benedick marketed itself as a haven for artists. Perhaps inevitably, it attracted a significant number of men who were also, in the euphemistic term of the period, “artistic.” Those tenants would be pleased that their apartment was only two blocks away from the notorious Slide at 157 Bleecker Street, identified by historian George Chauncey as the pre-eminent “fairy” bar in New York in the late 19th century.

The idea of an apartment building designed specifically for bachelors raised alarms among the guardians of virtue. “It has suddenly become the fashion,” one New York newspaper fumed, “to keep bachelor apartments, no matter how adequate to all rational requirements their family homes may be. Within two years a dozen or more magnificent buildings have been erected on the French flat plan, except that no women or kitchen are included.” These young men, by slipping their familial bonds, were evading one of the basic obligations of American manhood. “They are destitute of manly pride, but full of the foolish vanity of dandyism. Vicious also? Naturally.”

In 1888, a group of these vicious dandies rented an apartment in The Benedick to use as a private homosexual party space. Perhaps as a poke at the developer who had banned sinks from the rooms to avoid leaks of sewer gas into his new building, the group defiantly dubbed themselves the Sewer Club. The leaders (and chief financial supporters) of the club were the architect Stanford White and the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

“Stan” and “Gus” first met in 1875, and while both were attracted to women, and both would eventually enter into conventional marriages, the erotic charge that leapt between them was instantaneous. White and Saint-Gaudens began a long-term sexual relationship that was bawdy and playful. That relationship can be traced through their correspondence (though after White’s murder, his son sorted through the files and destroyed anything he found disturbing). In their surviving letters—which Saint-Gaudens refers to as “love-songs”—they call each other “Darling,” “Beloved Beauty,” “Doubly Beloved,” and “My Beloved Snooks.” In one letter Saint-Gaudens writes to White: “I’m your man to dine, drink, Fuck, bugger or such, metaphorically speaking”—though it is highly unlikely the men restricted themselves to metaphor; very little of their incessant sexual banter made any reference to women. Each would sign his letters to the other with a small caricature of himself, or decorate them with multiple drawings of erect penises. A standard closing consisted of the initials K.M.A., sometimes spelled out as “Kiss My Ass” or translated into French or Italian by Saint-Gaudens. Also employed were S.M.A., S.M.B., and S.M.C., as the sculptor urged the architect to orally stimulate various parts of his anatomy. One letter closes with Saint-Gaudens pleading, “Kiss me where I can’t.”

Many of the letters were standard business correspondence, as the men frequently worked on the same project (such as Trinity Church in Boston), but they devised a way to maintain the flirtation without shocking the secretaries. White would dictate or roughly draft a letter and leave it for an assistant (always male) to flesh out and type up on official firm letterhead. The assistant would leave the salutation and the closing of the letter blank, so that White could later pencil in his additions. As a result there are conventional business letters that open with a hurriedly jotted “Beloved!!”

No guest lists survive for the parties of the Sewer Club, of course, but from sketchy records we know the core members of the group. Besides White and Saint-Gaudens, the club included Gus’ brother Louis (also a sculptor), architect Joseph Wells, stained-glass artist Francis Lathrop, and painter Thomas Dewing. Probable guests included the architect Thomas Hastings and the painter and sculptor Francis Millet. Joseph Wells was employed by McKim, Mead & White, ostensibly as a draughtsman, but his superb design skills and encyclopedic knowledge of architectural history had a major influence on the style for which the firm would become renowned. Described as a shy, reserved and cynical bachelor, Wells was the “beloved friend” of Stanford White, but he also won the heart of Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The sculptor wrote a campy letter to Wells (employing the feminine form throughout): “Mon amour adorée, ma belle fille, je n’aime que toi, toi seul au monde—ton beau sourire me fait mourir d’amour.” [My adored love, my beautiful girl, I love no one but you, you only in the entire world—your beautiful smile makes me die of love.]

Thomas Hastings, another employee of McKim, Mead & White, also drew the amorous attentions of Saint-Gaudens. Hastings eventually entered into a partnership with his friend John Carrère, and when the firm of Carrère & Hastings was awarded a contract for the design of the New York Public Library, Hastings wrote to the sculptor for help in choosing artwork for the building—but asked Saint-Gaudens to be discreet with his reply: “Write me a letter which I can read to [the members of the library committee], that is, do not put too many love words and other things in it. But write me a love letter apart.” In 1900, Hastings married Helen Benedict, whom the gossip sheets chided for being more masculine than her husband. The couple lived largely apart, with Thomas keeping a penthouse apartment in the city, while Helen lived on Long Island with a female companion to whom she left her extensive fortune.

Painter Thomas Dewing, though married, continued to have erotic forays with both men and women. From Paris he wrote back to Stanford White in New York about an evening spent at a gay nightclub, where he and art collector Charles Freer spent “nearly two hours on a balcony watching 7 types [French slang for “guys”] jouir [to fuck]in 7 different manners from an old hairy pale-kneed grandfather down to the young Chicago sport who had stage fright.”

Francis Millet, though he married a woman (with Mark Twain as his best man) and was the father of four children, maintained long-term relationships with men, the most significant being with U.S. Army officer Archibald Butt (nearly twenty years his junior). The couple shared a mansion in Washington, D.C., where they often hosted large parties attended by the capital’s elite. After a visit to Europe, Millet and Butt were traveling back to America on the Titanic when it sank, and both men perished. The Butt-Millet Memorial Fountain in President’s Park near the White House was dedicated to the couple in 1913.

Few of the men who sported with the Sewer Club at The Benedick apartments were entirely homosexual. Many, like White himself, were husbands and fathers who also sought sexual encounters with both men and women. (White would be shot and killed in 1906 by the jealous husband of the actress Evelyn Nesbit.) Labels are subjective at best, but it would perhaps be most accurate to describe them as “bohemians,” men with artistic temperaments who held that sexual pleasures should not be hemmed in by the artificial guardrails of gender.

There are no traces of mauve-tinged fin de siècle decadence to be seen among the members of the Sewer Club—no mannered posing, no drooping ennui. Instead we find only a rambunctious, joyful refusal to live by society’s conventions. These men often needed to scrounge to pay the rent, or found themselves suddenly flush and just as suddenly over their heads in debt, but there was always someone able to throw a champagne party at Delmonico’s. They married for financial security or social respectability—often to women who had no more interest in a traditional union than they did and who welcomed the smokescreen. So they cheated on their wives with their boyfriends and cheated on their boyfriends with chorus girls. New York would not see such an unabashed celebration of pansexual hedonism again for nearly a century. The members of the Sewer Club and their guests were free spirits with extraordinary talent who produced some of the most sublime architecture and decorative art that the country has ever seen. They were a guild of skilled craftsmen bound together by a complex web of affections, and they used a bachelor apartment in The Benedick as their own private backroom cum frat house.

Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner labeled this period of our history the Gilded Age. For a few fortunate men over a few golden decades, New York City’s bachelor apartment buildings provided a safe private space for sexual nonconformists to glitter and be gay.

References

Baker, Paul R. Stanny: The Gilded Life of Stanford White. The Free Press, 1989.

Broderick, Mosette. Triumvirate: McKim, Mead & White: Art, Architecture, Scandal and Class in America’s Gilded Age. Alfred A. Knopf, 2010.

Hinman, Suzanne. The Grandest Madison Square Garden: Art, Scandal, and Architecture in Gilded Age New York. Syracuse University Press, 2019.

William Benemann is the author of Unruly Desires: American Sailors and Homosexualities in the Age of Sail, and Men in Eden: William Drummond Stewart and Same-Sex Desire in the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade.

Discussion1 Comment

Interesting. I am writing a TV series about a gay Handel in the 1700s. In London there was a club, the Kit-Cat Club, that I have written into my limited TV series about Handel’s life, as the meeting place for his annual reunion with his mates. Would love to compare notes.