ADAM AND EVE APPEARED to a woman named Ann Lee in Manchester, England, in 1770. An unhappily married woman who had endured the deaths all four of her infant children, Lee had been following various fringe religious movements when the biblical couple suddenly materialized before her—not eating of the forbidden fruit as might be expected, but instead engaging in sweaty, grunting, grappling coitus. Lee was thoroughly disgusted. Her disturbing vision would lead her to America, where she founded one of the major religious sects of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, one that held as its primary tenet that all sex of any kind—whether in marriage or not, for reproduction or mere pleasure, with another or alone—was bestial and degrading and vile.

As the barrier of the Appalachians toppled and the country spilled westward toward the plains, many Americans found the absence of geographic limits disorienting, and they searched for ways to safely circumscribe their personal world. In matters religious, this often meant turning to faith communities with clear and strict regulations, authoritarian structures with inflexible rules not open to interpretation. In a world that seemed increasingly scattershot, America’s new religions offered order and discipline. For members of Ann Lee’s United Society of Believers, popularly known as the Shakers, the requirement of celibacy promised a welcome release from the messiness of sex.

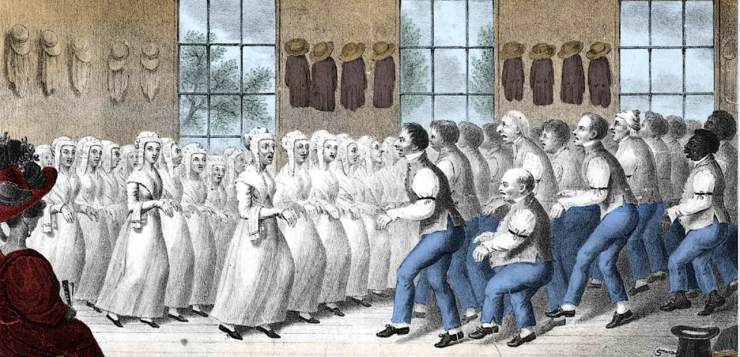

The Shakers offered a particularly attractive alternative for women. As a religion founded by a woman, it insisted on the equality of the sexes. Lee proclaimed herself the second coming of Jesus Christ, this time in a female body, and taught that God was both male and female. She insisted on gender parity in the governance of Shaker villages and encouraged women to speak their minds. In her communities, men and women would live parallel but partitioned lives, with many buildings designed to have separate entrances and separate staircases to minimize intermingling of the sexes. Labor was strictly divided along gender lines, and while “women’s work” of sewing, washing, cleaning, and cooking was arduous and unending, the heavy labor of planting, harvesting, and construction was handled by the men. Unlike in female-only communities, Shaker women could confine themselves to the traditional “feminine sphere” of work, enjoying a close, supportive sisterhood while still receiving all the benefits of having a man around the house—without the pesky demands for sex. And in a world where infant mortality and death in childbirth were tragically common, deciding to avoid heterosexual sex could be a life-saving choice for a woman.

William Benemann is the author of Unruly Desires: American Sailors and Homosexualities in the Age of Sail and Men in Eden: William Drummond Stewart and Same-Sex Desire in the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade.