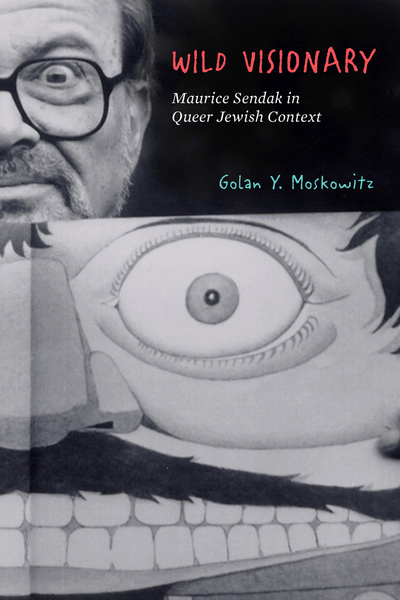

WILD VISIONARY

WILD VISIONARY

Maurice Sendak in Queer Jewish Context

by Golan Y. Moskowitz

Stanford U. Press. 298 pages, $90.

IN TENNESSEE WILLIAMS’ Orpheus Descending (1957), local bad girl Carol Cutrere laments the individual’s loss of independence in narrow-minded Two River County, Mississippi. “This country used to be wild, the men and women were wild and there was a wild sort of sweetness in their hearts, for each other, but now it’s sick with neon, it’s broken out sick, with neon, like most other places.” Carol’s complaint is proven justified when a sexually seductive interloper named Val Xavier—who refuses, he says, to be sentenced “to solitary confinement inside [my]own skin”—is eventually castrated with a blowtorch and lynched by the intolerant townspeople. But Val leaves behind his snakeskin jacket, allowing Carol to reflect on how “wild things leave skins behind them, they leave clean skins and teeth and white bones behind them, and these are tokens passed from one to another, so that the fugitive kind can always follow their kind.”

The tension identified by Williams between civilization and nature—between social conformity and disruptive passion, or between stultifying heteronormativity and queerness—neatly frames the issues addressed by Golan Y. Moskowitz in Wild Visionary, an illuminating study of the innovative children’s author and illustrator Maurice Sendak (1928–2012). Williams’ “fugitive kind” are those people who, despite communal censure, follow their heart’s urges, no matter how dark and strange. They have the strength to stare down the oppressive judgments of social authorities because they’ve discovered in the wildness of nature “tokens” left behind by fellow fugitives. These they can follow when setting out on their own journey into the darkness that pulsates beyond the neon-lighted safe and familiar.

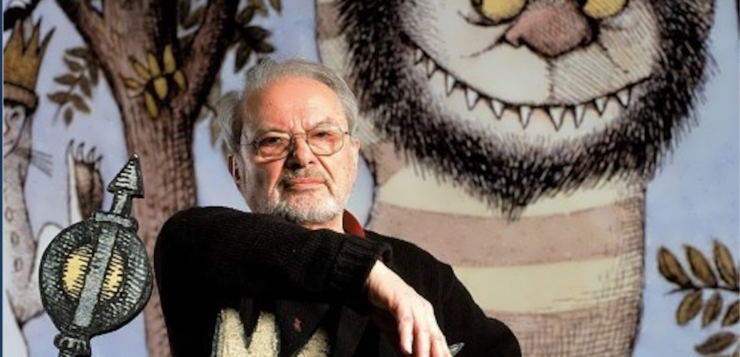

Similarly, Moskowitz reveals Sendak to have been a pivotal proponent of the necessity of exploring and even indulging “the wild” in modern life. The child of lower middle-class Yiddish-speaking immigrants who lived in Brooklyn but agonized daily over family members in Poland lost during the Holocaust, Maurice grew up preternaturally aware of the world as a place of threat and trauma. (In 1932, as the news media obsessed over the kidnapping and death of the Lindberg baby, Sendak’s father slept on the floor of his children’s bedroom, baseball bat in hand, to defend them against a similar possible abduction.)

But the adolescent Sendak’s growing awareness of his sexual difference and fear of his large, extended family’s disapproval left him feeling as deeply threatened by the domestic order as by the unfamiliar and chaotic world outside the local Jewish immigrant community. Little wonder that when Sendak began writing and drawing, his imaginative universe was dominated by night terrors that children must learn to negotiate on their own when their parents prove absent or oblivious to their needs. The roots of Sendak’s homosexuality, Moskowitz hints, may lie in his having shared a bed with his older brother Jack, who’d protect Maurice from bedbugs by having the smaller boy lie on top of him at night. (Kids do the queerest things.) Yet in a society that tended to equate homosexuality with bestiality and demonism, Sendak struggled as a young adult to control his sexual impulses, going so far as to propose marriage to a woman he’d impregnated, only to suffer an emotional breakdown before the wedding could take place.

Equal parts social history and psychobiography, Moskowitz’ study of Sendak proves a case study on the ferocity of gay creativity—the need for gay men to fashion an imaginative world where they can behave in ways that, if freely expressed, would result in social ostracism or even physical violence. Sendak transformed the terrain of writing for and about children by acknowledging their sexuality and their dark emotions, and by refusing to idealize children as such writing traditionally did. Sendak presented a world in which adults are oblivious to the traumas that children suffer, so that children must rely upon their inner resources, especially their imaginations, to defeat the forces that terrorize them.

The great takeaway from Moskowitz’ insightful study is the extent to which Sendak was exploring his own sexual conflicts as he wrote about children. In Sendak’s world, the child who is intuitively aware of the threatening aspects of human existence, yet who is forcibly kept in an unnatural state of innocence by ignorant yet well-intentioned parents, becomes a stand-in for the gay person who must find a way to negotiate the wild sexual urges with which their parents cannot sympathize. Because of the facile identification of homosexuals with child molesters in mid-century American consciousness, Sendak feared losing the support of teachers and librarians if he were to acknowledge his sexuality in public. As a result, although he lived his entire adult life as a gay man, he did not come out publicly until age eighty, following the death of Eugene Glynn, his partner of fifty years, four years before his own death.

Moskowitz has reclaimed Sendak as one of great gay writers and artists of the 20th century. Sendak wrote Where the Wild Things Are (1963) while summering on Fire Island, where he could escape from the stultifying confines of Manhattan and enjoy a physically liberated existence. Similarly, In the Night Kitchen (1970), whose unabashed homoeroticism caused it to be banned by some libraries, was written in the apartment that he shared with Glynn, just a block from the Stonewall Inn. Astutely analyzing drafts of Sendak’s narratives, and the progressive stages of his illustrations, Moskowitz demonstrates the sometimes subtle, but often quite overt, ways in which Sendak blurred gender lines and celebrates queer relationships.

Among the surprises in Wild Visionary is the extent of Sendak’s devotion to Herman Melville, for whose Pierre, or The Ambiguities he produced a series of wonderfully homoerotic illustrations. And I was previously unaware of Sendak’s work for AIDS causes. Seeing AIDS as a social trauma on a par with the Holocaust, Sendak produced the text and illustrations for We’re All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy (1993), an AIDS-themed children’s story. In later life, when he lamented that he could not write even more openly about gay matters, he embarked on a new career designing sets and costumes for operas and ballets, including an important collaboration with Angels in America playwright Tony Kushner.

It’s unfortunate that Sendak seems never to have met fellow gay artist Tennessee Williams, for Williams would surely have recognized how Sendak’s books and drawings function as tokens that the artist has left behind so that fugitive children can follow their kind. They would no doubt have had much to share about the heroic yet traumatizing need to go where the wild things are, and Sendak’s tiger-suited Max (the protagonist of his most famous children’s book) might have taught Williams’ Val Xavier something about survival.

Raymond-Jean Frontain is professor of English at the University of Central Arkansas.