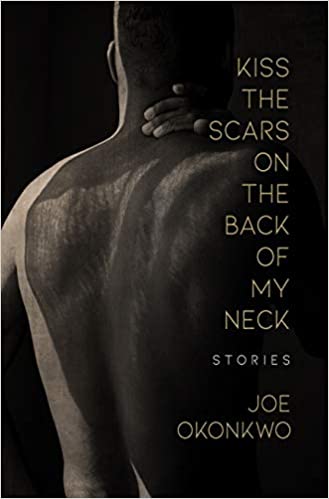

KISS THE SCARS ON THE BACK OF MY NECK: Stories

KISS THE SCARS ON THE BACK OF MY NECK: Stories

by Joe Okonkwo

Amble Press. 181 pages, $16.95

KISS THE SCARS on the Back of My Neck is a collection of short stories, many of them featuring gay Black men. Several, including the title story, are linked by two recurring characters whose lives are depicted from childhood to adulthood in separate tales, until the final story brings them together.

Okonkwo explores the complexities and intersections of sexuality, race, and class. The first story, “Picnic Street,” follows Justine, who has moved back to small-town Mississippi with her young son Paulie after leaving her husband. Intelligent, with sophisticated tastes, someone who knows Les pêcheurs de perles to be “one of the most sublime yet least performed operas in the repertory,” Justine stands out here, where many of her neighbors criticize her for liking things that only “white folks” enjoy and leaving her husband. Even her own sister, whose house she and Paulie are staying in, does not understand her, spending much of her time in her bedroom. Justine carefully navigates her way through this difficult situation, scolding Paulie for leaving out his Legos (and risking making her sister angry), while standing up to a mean-spirited neighbor whose children, Justine thinks, “would not attain anything better than what they had now.”

Her son Paulie is an unusual child who has lengthy conversations with an imaginary friend, Boris, and asks his mother perceptive questions that unnerve her. His life develops in other stories. In “Paulie,” he is a sixteen-year-old boy carrying around a book by an artist who paints religious and classical scenes featuring “sexy” Black men. Full of self-assurance, he uses elevated language, like “placidly,” and enjoys the ease with which he can hurt his mother by just a few choice words. He looks down on his younger half-brother William, to whom his mother seems to pay more attention, while admitting that William “is beautiful.” Paulie has had a sexual encounter with the friend of his bully who now will not look at him, and he admires his mother’s white boyfriend Barrett, whom he nicknames “Bear.” In revenge for missing his favorite artist’s museum exhibit due to his brother’s tantrum, he manipulates Bear into breaking up with his mother. This story captures the sympathetic and sinister aspects of Paulie’s personality, who will return in a subsequent story.

The other recurring character is Cedric, introduced as a young boy in “The Girl’s Table.” A soft-spoken boy who regularly sits at the girl’s table and is the target of spitballs, tripping, and insults, he is unable to fight back against his tormenters, even though “Daddy tell me to fight.” One of his bullies finally does something shockingly violent to him, all because “he just a boy who sit with the girls.”

The title story, also the last, brings together Paulie and Cedric in an almost operatic tale. In fact, they meet at the opera, Cedric standing in the back as Paul, a regular contributor to the opera house, invites him to sit next to him, having contrived to expel his neighbor from their seat. Paul has become a successful, wealthy artist who is haughty and manipulative. He sneers at Cedric for calling the performance a “show.” Once the relationship between them develops, he helps Cedric find a job and pays for a certification course but does not invite him to his functions, until Cedric shows up to one unannounced. Cedric does not shy away from telling Paulie exactly what he thinks. This is a relationship of two strong personalities, but ultimately, Cedric has most of the power. ____________________________________________________

Charles Green, a frequent contributor to these pages, is a writer based in Annapolis, Maryland.