Cedric Morris and Christopher Wood: A Forgotten Friendship

An exhibition in three English counties

(Norfolk, Kent, and Cornwall), 2012-13

Catalogue by Nathaniel Hepburn

Unicorn Press. 320 pages, $35.

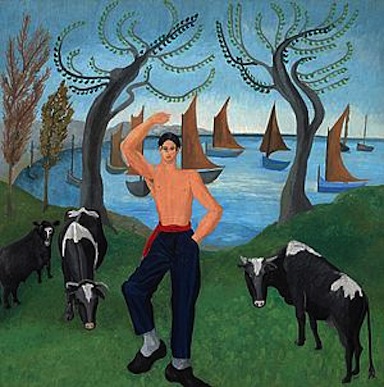

THIS IS a remarkable exhibition to be found touring three lesser-known provincial art venues in southern England. One of the venues, Falmouth, fully makes sense, in that many of the paintings by Cedric Morris and Christopher (“Kit”) Wood gathered here relate to periods spent in St. Ives and across Cornwall, and they feature the usual subjects: fishermen, village life, rural scenes, and tin miners. But other paintings describe a very different pair of trajectories, which for both artists encompassed scenes from London, Paris, Brittany, and Suffolk.