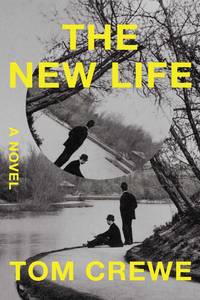

THE NEW LIFE is a debut novel by a young English writer who has all the gifts—a distinctive, pitch-perfect style; a vast erudition, solid and detailed, about his period, the 1890s, including a doctorate from Cambridge in 19th-century British history; a dramatic feel for the history of ideas; a deep psychological grasp of his male and female characters; a gift for determining which details should be observed and which trimmed away. And the wonderful Victorian art of entertaining while edifying.

This novel, unlike Victorian fiction, is full of explicit sexuality. The opening scene will cost gay male readers gallons of cum and excite a few women, perhaps. John Addington, a solid citizen in his fifties, is standing behind another man in a crowded train car—so crowded that he is pressed against the man’s buttocks and can’t move an inch. He gets an erection and the man begins deliberately to move his ass against Addington’s cock. Soon John comes cataclysmically—and wakes up beside his wife, Catherine. He sneaks off to hide his semen-heavy nightshirt in the dirty laundry.

We’re introduced to Henry Ellis, his collaborator, through another solitary, inadmissible kink. He’s turned on by the thought of women urinating, which he discovers when he sees a female vagrant pissing outside his windows.

The plot is about how these two well-educated, repressed gentlemen write a book together on sexual inversion, a study that goes all the way from homosexuality among the ancient Greeks to modern, anonymous reports on the life stories of inverts. Presiding over everyone are the contemporary American poet Walt Whitman and his “love of comrades” and Edward Carpenter, an early advocate for gay rights, vegetarianism, socialism, and the simple life.

In the midst of Ellis’ and Addington’s collaboration, the Oscar Wilde trial occurs, and English inverts go clambering back into their closets. Or move to Europe, where there are no laws against homosexuality (France) or where people look the other way if the inverts are foreigners or aristocrats (Italy, Spain). Ellis and Addington, however, decide to persist with their “impossible” book, partly in acknowledgment of Ellis’ wife, who is living with an outspoken, fearless lesbian named Angelica.

Crewe seems to be influenced primarily by Henry James in the weird directness of the dialogue and the muted violence of descriptions (as opposed to James’ super-subtle, confusing renditions of psychological states). The New Life is, among other things, a novel of ideas (a recurring phrase is “we must live in the future we hope to make”), which means that Crewe’s people are obliged to say what they really mean, unlike most fictional characters, who say something vague or deceptive. (Elizabeth Bowen’s rule for dialogue, for instance, is that characters must always say something to deceive others or themselves.)

These are not woolly ideas such as those presented by D. H. Lawrence (the fatal attraction of the primitive, of racial difference, of the unconscious) but clear-cut progressive ideas such as the value of women’s rights and free speech and of same-sex love. John and Henry, despite the opposition of the law and of the prevailing mores, believe their book is irrefutable and bound to lead to the New Life, a utopian state in which people will be able to express their authentic desires. This new existence is difficult for our characters to achieve even in their own behavior, partly because they believe that their respectability—their marriages—is their best defense in a Victorian world, partly because of the disapproval of their more conventional children, and partly because of their own inner ambivalence as they explore this dangerous moral territory.

Crewe has a gift for metaphor, which Aristotle thought was the most important of a writer’s gifts and the only one that couldn’t be learned. “Occasionally parties of sunlight roved over the grass, past the determined little stream and the stretching fields, which sent up a glitter in response.” Here, all the comparisons are prompted by the verbs and adjectives. “He saw other people purely as they presented themselves to him, as if he were a backcloth receiving a projection.”

Occasionally the characters realize that they are briefly living animals with strange limbs in an arbitrary space. “There were several small moments of breathing proximity, when, standing side by side, John was aware of heat gently beating from Frank’s cheek and could almost feel … the quantity of Frank’s body under his clothes.” These are not a few gems I’ve collected but the normal rhetoric of this prose, page after page. “Two men in a small room, down a dark corridor, in a big house, in a heartless city, on an island lashed round by cold sea.” A lovely moment like this that acknowledges the smallness and contingency of our existence is the kind editors circle and want writers to omit.

Throughout the book there are wonderful observations of fog and light worthy of the Ford Madox Ford of Parade’s End. We remember that in Victorian times London was often obscured by impenetrable fog and that pedestrians could see no more than a few feet in advance and needed to hire guides to lead them to specific destinations. “The fog encased them. John could see the stone underfoot and Frank, but no further. What must be the street lamp figured as a brighter, faintly glowing patch of yellow in an indeterminate space higher up. They listened: there was a distant fall of hooves, slow and muted as a funeral march. A pale faraway shout. The sky lurked, massive and obscure.” The great city with its pea-soup fogs, its seething underclass, and its criminals is a perfect setting for the sex secrets of even its rich citizens, as revealed by The New Life.

This novel shows that the struggle to come out, due to the strictures of the dominant society, has always been painful and hard won. We like to think that same-sex love isn’t just defensible but also beautiful, not only in its normalizing Pete Buttigieg version, imitative of heterosexual marriage, but also in its quirkiest manifestations. As Anne Enright says in her blurb: “Tom Crewe’s forensic love of the physical puts the body back into history.” We can feel these queer bodies as they make their passionate, problematic love.

Edmund White is the author of the forthcoming novel The Humble Lover. His A Boy’s Own Story will soon be published as a graphic novel.

Discussion1 Comment

My only regret in listening to the audiobook is that I couldn’t write down some of the most lyrical and brilliant metaphors — thank you, Edmund White, for citing a few. Another problem with listening (mostly) at the gym was the unexpected flowing of the blood to the nether regions that occurred during some of the exquisitely erotic yet somehow restrained sexual passages. I’ve cited his book on a substack thread about how to write sex; “Like Tom Crewes!” (Freddie Fox did an excellent narration.)

The New Life went immediately onto my top 5 list of favorite books. Bravo, Tom.