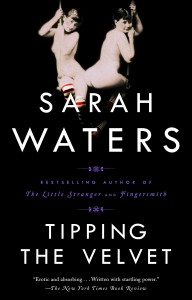

Tipping the Velvet

Tipping the Velvet

by Sarah Waters

Riverhead Books/Penguin Putnam

472 pages, $25.95

Editor’s Note: With the exception of the following, all of the reviews in this “best of” issue are previously unpublished, and they refer to new books and films.

The following piece, which appeared in our Fall 1999 issue, reviewed a book by Sarah Waters, Tipping the Velvet, a new edition of which has just been published by Little, Brown Book Group. This review of Waters’ debut novel seems prescient in light of this writers’ subsequent critical and popular success as a lesbian novelist. The GLR would go on to review three more of her novels in subsequent issues. Reviving this review is also a way to thank its author, Martha E. Stone, for her extraordinary service to the GLR over the years.