Death In Venice

Death In Venice

by Will Aitken

Arsenal Pulp Press

187 pages, $14.95

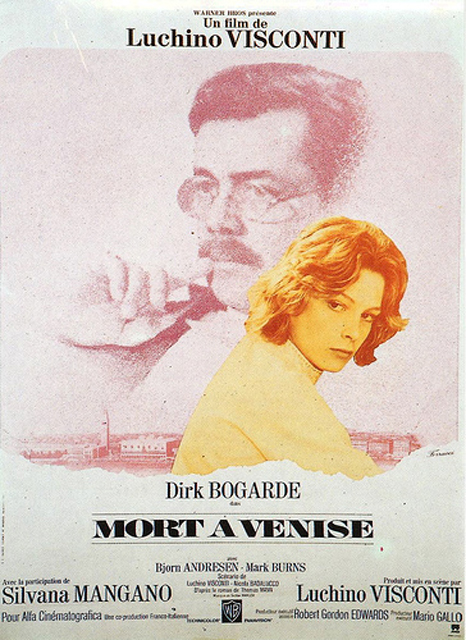

AS a longtime devotee of the films of Luchino Visconti (1906–1976), I’m thrilled to report that this new critical study on the work of Visconti is an admirable addition to any film aficionado’s library. Author Will Aitken, a well-known Montreal-based professor of film, has produced an in-depth examination of Visconti’s Death In Venice (1971).

Visconti was born into a fabulously wealthy family and raised as a privileged Italian aristocrat. His mother, Donna Carla, loved music and was a gifted pianist. She dressed in gowns in the Art Nouveau style and was herself a patron of the arts. Before going to the opera, his father, Don Giuseppe, was known to apply mascara to enhance his dark eyes, and facial powder to accentuate the paleness of his skin in contrast to his curling black hair.

Duke Guido Visconti, Luchino’s paternal grandfather, was president of and a major financial contributor to La Scala, the world-famous opera house. The Duke also “performed” in many operas: he liked to dress as a ballerina (he covered his very dark beard under layers of lace) and danced with the corps de ballet. Aitken reports that Arturo Toscanini, La Scala’s conductor from 1896 to 1908, was disgusted by the Duke’s behavior and furious at the Visconti family for acting like they owned the opera house.

Death in Venice provides a whirlwind tour of Luchino Visconti’s artistic and political life story. We learn of his obligatory trip to Paris in the 1920’s, where he met Jean Cocteau and Coco Chanel, among others, and of his work with the famous French director Jean Renoir. We learn of his early attraction to fascism and his subsequent embrace of communism. As an anti-fascist, Visconti worked in the Italian resistance to overthrow Mussolini and the Nazis once they marched into Rome. In 1944, he hid from the fascists with the famous Italian actress Anna Magnani and her son. He was finally arrested by the fascists on April 15, 1944. While in prison, he was beaten and starved. On June 3, 1944 he was freed from prison when Allied troops entered Rome.

At some point the details of Visconti’s life begin to intertwine with the creation of Death In Venice. Thomas Mann’s novella was one of three books that Visconti carried with him at all times from an early age, along with André Gide’s The Counterfeiters and Proust’s Recherche, in specially made red-leather bound, gold-embossed chapbook editions. Death in Venice haunted Visconti throughout most of his artistic career. The novella tells the tale of an aging, famous scholar who, despite all his bourgeois morality and repression, falls in love with a young boy while on a trip to Venice. The 1912 novel was based on an incident in the author’s life involving his obsession with a young Polish boy (Wladyslaw Moes) while vacationing in Venice.

At some point the details of Visconti’s life begin to intertwine with the creation of Death In Venice. Thomas Mann’s novella was one of three books that Visconti carried with him at all times from an early age, along with André Gide’s The Counterfeiters and Proust’s Recherche, in specially made red-leather bound, gold-embossed chapbook editions. Death in Venice haunted Visconti throughout most of his artistic career. The novella tells the tale of an aging, famous scholar who, despite all his bourgeois morality and repression, falls in love with a young boy while on a trip to Venice. The 1912 novel was based on an incident in the author’s life involving his obsession with a young Polish boy (Wladyslaw Moes) while vacationing in Venice.

Visconti’s adaptation of the novella altered the profession of the protagonist, von Aschenbach, from a writer to a composer who bears a strong resemblance to Gustav Mahler. In the film, Aschenbach (played by Dirk Bogarde) becomes obsessed with Tadzio (Bjorn Andresen), a beautiful and flirtatious adolescent boy. A constant presence in the film is the music of Mahler, notably the Adagio movement from his Fifth Symphony. The film is bathed in the longing notes from this work, which Visconti uses like a Greek chorus to comment upon the action and heighten the emotional pitch.

Another haunting presence in the film is cholera. The disease is spreading through Venice and threatens to become an epidemic. Visconti uses this pestilence as a metaphor for the decay of Aschenbach’s bourgeois values and morality. Aitken proposes that Visconti is suggesting a connection between homosexual desire and “contamination.” This can explain Aschenbach’s rapid dissolution and decline once his homosexuality rises to the surface. However, given Visconti’s leftist politics, it can also be argued that Aschenbach’s descent into forbidden desires is itself a result of the hypocrisy and repression of bourgeois society. In this and in other novels, Mann suggests that what brings down a protagonist is the suppression of forbidden desires rather than their open expression.

Yet another reading of Visconti’s interpretation of Death In Venice is that the director sets out to portray Tadzio as the epitome of “Beauty” harking back to the Greek ideal as discussed in Plato’s Symposium. Aschenbach’s pursuit of this impossible love is related to his pursuit of the Classical concepts of Beauty, Truth, and Love. Aschenbach dies not from his love of Tadzio but from eating a cholera-contaminated strawberry. His last act is to reach out from afar to Tadzio, who’s standing like a young god in the ocean, in an attempt to join with his muse.

Aitken maintains that Death In Venice “is the closest [Visconti] got to autobiography.” In the film, Visconti depicted the dying world of pre-World War I Venice. It was a society of sharp social divisions, of vast wealth contrasting with grinding poverty, as symbolized by cholera victims dying in the street. The film is set in the Hotel des Bains, which is where the Visconti family vacationed in the early 1900’s. Luchino knew the excesses of his class, and he understood their hidden desires.

Visconti had conflicted feelings about his own homosexuality. Aitken describes him as a “highly conservative man, especially about the importance of the family.” At one point he contemplated marriage, but this did not happen. He didn’t deny his sexual orientation but didn’t admit to it either, suggesting that he had one foot in and one foot out of the closet. Toward the end of his life, in the late 1960’s, he was asked if he wanted to go to a gay bar. He declined on the pretext that such places were “vulgar.”

Visconti was a product of his Catholic upbringing, which ensured that he would be tormented by sin, especially its sexual variants. On the other hand, whatever his inner turmoil, he had the money to keep lovers, such as Helmut Berger, whom he directed in The Damned and in Ludwig, and to conduct affairs with the likes of Leonard Bernstein and Franco Zeffirelli. In addition, he adored Maria Callas. Aitken reports that he would spend time “caressing [Callas’] long black hair for hours because it reminded him of his mother’s.”

This account of Visconti’s life and work is insightful and informative, and Aitken’s writing style is engaging. The book also offers some interesting comments on several other Visconti films, notably Bellissima (1951), The Damned (1969), and Ludwig (1972).

Irene Javors, a psychotherapist based in New York City, is the author of Culture Notes: Essays on Sane Living, ACFEI Media, 2010.