WHAT WAS KNOWN in the early to mid-1960s as the Mimeograph Revolution spawned a vast number of short-lived publications, printed in small runs on cheap paper. Many were filled with works by writers and artists who have since become famous, and the few extant copies of these periodicals are collector’s items. One such magazine was called C: A Journal of Poetry, whose September 1963 cover was designed by none other than Andy Warhol. Indeed it was the first time that Warhol used a Polaroid camera to take black-and-white portraits for a magazine cover, which has been described as one of his “earliest silkscreened multiples.”

Warhol and the Factory crowd collaborated on a publication that would later coalesce into Interview magazine. A humble rag at first, Interview has undergone vast changes over the decades and is still being published today, both in print and electronically. The origin stories vary with the teller, including the initial impetus for starting the magazine, and they range from frivolous to deeply thoughtful. In no particular order, the founders may have launched Interview for any one of the following reasons (or some combination thereof):

Warhol and the Factory crowd collaborated on a publication that would later coalesce into Interview magazine. A humble rag at first, Interview has undergone vast changes over the decades and is still being published today, both in print and electronically. The origin stories vary with the teller, including the initial impetus for starting the magazine, and they range from frivolous to deeply thoughtful. In no particular order, the founders may have launched Interview for any one of the following reasons (or some combination thereof):

- To score free tickets to the New York Film Festival. Interview was originally conceived in 1969 as a 28-page magazine of film criticism, which would have given the Warhol entourage an entrée into the New York film scene. Its original name was inter/VIEW, printed in this unusual style as designed by Gerard Malanga, with the tagline, “A monthly film journal.” Malanga, who copyrighted it as “Poetry in Film, Inc.,” had developed an interest in the intersection of poetry and the visual arts while in high school, and he was one of Warhol’s earliest silkscreen assistants. He and critic Edwin Denby were the subjects of that cover portrait for C: A Journal of Poetry. Even before launching inter/VIEW, however, Warhol and Malanga had planned to publish a literary arts magazine called Stable (probably named in honor of the art gallery where his Pop paintings debuted, and to be published by the owner of that art gallery). The plan was to publish art and poetry written by such Beat writers as Diane Di Prima, Ted Berrigan, and John Ashbery, but it never got beyond the advertisement stage. Soon, though, Warhol became dismissive of poetry, proclaiming it “old fashioned.”

- To give the “Factory Kids” something to do. The magazine certainly gave something for Malanga to do, but Warhol had—or so it is believed—other plans for the Factory denizens, particularly his close friend Brigid Berlin, daughter of publishing mogul Richard Berlin, who had begun his career as someone known for his prodigious capabilities in ad sales. Warhol hoped that Brigid had inherited these abilities, but apparently she had not, or in any case she had no interest in selling advertising. In the end, both she and Pat Hackett, a long-time Factory employee, worked behind the scenes, as editors. Both were highly attuned to Warhol’s style and personality, aware that they should leave in the conversational pauses and inconsequential chit-chat that others would edit out. They had transcribed many hours of tape recordings of mundane daily conversations, some of which made their way into a, A Novel (1968) and The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again (1975). Warhol was fascinated by the tape recorder—he called it “modern and real” and referred to it as his wife.

- To pay homage to View magazine, and its founder Charles Henri Ford. Ford was best known as co-author, with Parker Tyler, of the gay classic The Young and Evil (1933). Ford and Warhol had met in 1962 at a party, became friends, and sometimes attended underground film screening together, where Warhol was introduced to major cutting-edge filmmakers. It was Ford who introduced Malanga to Warhol. View, subtitled “Through the Eyes of Poets,” had begun in 1940 and introduced American readers to “surrealism, existentialism, and their sources,” as well as interviews with “cult poets” such as Wallace Stevens, whose interview in the premiere issue was titled “Verlaine in Hartford.” View was acclaimed by critics as “one of the most important avant-garde magazines of the 1940s.”

Emblazoned across the first cover of inter/VIEW were the prescient words: “First Issue Collector’s Item.” The cost for a single issue was 35 cents, for a yearly subscription (twelve issues), $3.50, and for a two-year subscription, $7.00. That first issue featured the unclothed stars—James Rado, Gerome Ragni, and Factory superstar Viva—of the film Lion’s Love. Rado and Ragni, who had written the book and lyrics of Hair and starred in it, were lovers, as Rado stated in a 2008 interview in The Advocate. The three are joined on the cover by a fully clothed Agnès Varda, director of Lion’s Love, which The New York Times called “very funny … cool and loose and honest.” That issue contained interviews with George Cukor and Michael Sarne, director of the film version of Myra Breckinridge.

For its first year, inter/VIEW was an underground film magazine, serving to promote Warhol’s own movies, such as Flesh and Trash. It provided Warhol easy entrée to the film crowd. Who could turn down an invitation to do an interview for inter/VIEW? Soon after the magazine started, Bob Colacello, a master’s degree student in film criticism at Columbia, was hired as an editor after his review of Trash was spotted in a small alternative magazine by Soren Angenoux, one of inter/VIEW’s many early editors. (There had been twelve in four years.) Along with editor Glenn O’Brien, Colacello gave the magazine a more professional appearance, finding “real” writers willing to work for little pay. The magazine set out to review every film released in New York while toning down some of the puffery of the interviews themselves. Early issues were typeset on cheap newspaper by an “old hippie,” John Wilcock, publisher of Other Scene and known as “the Zelig of ’60s counterculture publishing,” in the words of a 2012 Atlantic interview. There were only a few distribution points in those early years: the lobbies of MoMA and Anthology Film Archives, as well as two small Village vintage shops. Colacello, who soon became a member of Warhol’s innermost circle, would be closely affiliated with Warhol throughout his entire life.

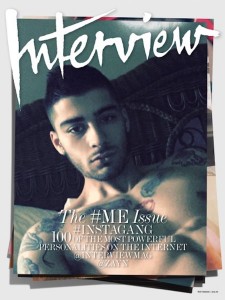

Beginning in 1972 (by which time the magazine was called Andy Warhol’s Interview) and continuing for fifteen years, cover art was provided by Richard F. Bernstein, who died of complications from AIDS at the age of 62 in 2002. In the words of his New York Times obituary, his portraits—over 120 of them, airbrushed and enhanced with pencil or pastel marks—captured an “idealized glow that was intensified by the large format of the magazine.” A 1984 collection, Megastars, contains many of those covers. It was not uncommon for Warhol to sign a cover, making Bernstein’s work look as if it were Warhol’s own. As the years went on, the magazine became more and more professional, kick-started by Warhol’s desire to hang out with the rich and famous rather than the underground crowd. The change in focus also brought in new, big-budget advertisers. Francesco Scavullo (famous for his Cosmopolitan magazine covers) became the cover photographer of choice. The magazine became a showplace for pioneering photography, featuring works by Mapplethorpe, Herb Ritts, Mario Testino, and David LaChapelle.

The complete list of the famous interviewing the famous is far too long to include here, but among the more illustrious pairings were: Mae West interviewed by Anjelica Huston; Troy Donahue interviewed by Divine; Lee Radziwell interviewed by Warhol; Calvin Klein interviewed by Bianca Jagger and Warhol; Mick Jagger interviewed by Lee Radziwll; Salvador Dalí interviewed by Factory superstar Candy Darling “with additional dialog by Francesco Scavullo.” Truman Capote, who was greatly admired by Warhol in his years of struggling to make a name for himself, was a frequent contributor. He was interviewed in the January 1979 is-sue, two years after Warhol’s name had been removed from the name of the magazine, streamling it to Interview. Warhol was convinced that the Republicans, then in power with Ronald Reagan’s 1980 election, could be a rich source of portrait revenue, so he interviewed Nancy Reagan and put her on the December 1981 cover, a decision for which he received a great deal of flack.

After Warhol died in 1987, the Andy Warhol Foundation had to divest itself of any profit-making operations. The magazine was sold to Brant Publications, which in 2004 published a book in seven volumes titled Andy Warhol’s Interview: The Crystal Ball of Pop Culture, edited by Ingrid Sischey and Sandra J. Brant, with a cover price of $475. It consisted of a plywood carrying case designed by Karl Lagerfeld, with wheels and a telescoping handle, to hold and transport the weighty set, introducing a novel element of mobility into the culture of book buying and ownership. Contained in the book were reprints of the first ten years of the magazine, reprints of covers and interviews from later years, along with profiles of personalities, stars, directors, and a generous serving of celebs interviewing other celebs. A review of this work in the May-June 2005 issue of the magazine Print refers to the “stultifying narcissism” evinced in such meta-interviews. Warhol was known to be jealous of Jann Wenner’s success with Rolling Stone magazine, so it’s no surprise that the early issues of inter/VIEW “resemble[d]a knock-off of the original Rolling Stone,” according to the Print piece.

Ingrid Sischey, who had been editor-in-chief of Interview from 1989 to 2008, died in 2015. She and Sandra Brandt—previously married to publisher Peter Brandt—had been lovers for a quarter century. Sischey was succeeded by the current editor, Keith Pollock, a digital and print magazine veteran. Historically, Interview was an important showcase for photographers, whose portfolios were always given serious consideration. The magazine’s extra-large format (11 by 17 inches at its peak size) created an æsthetic experience that standard-sized magazines could not equal. The publication of the print magazine is still a monthly event, but interviews continue to appear unabated on the Interview website, which every Wednesday reprises an interview from the trove of past issues.

Author’s note: Lucy Mulroney’s Andy Warhol, Publisher, a 2013 doctoral dissertation for the University of Rochester, was of great help in the writing of this article, as was the website www.Warholstars.org.

Martha Stone is the literary editor of this magazine.