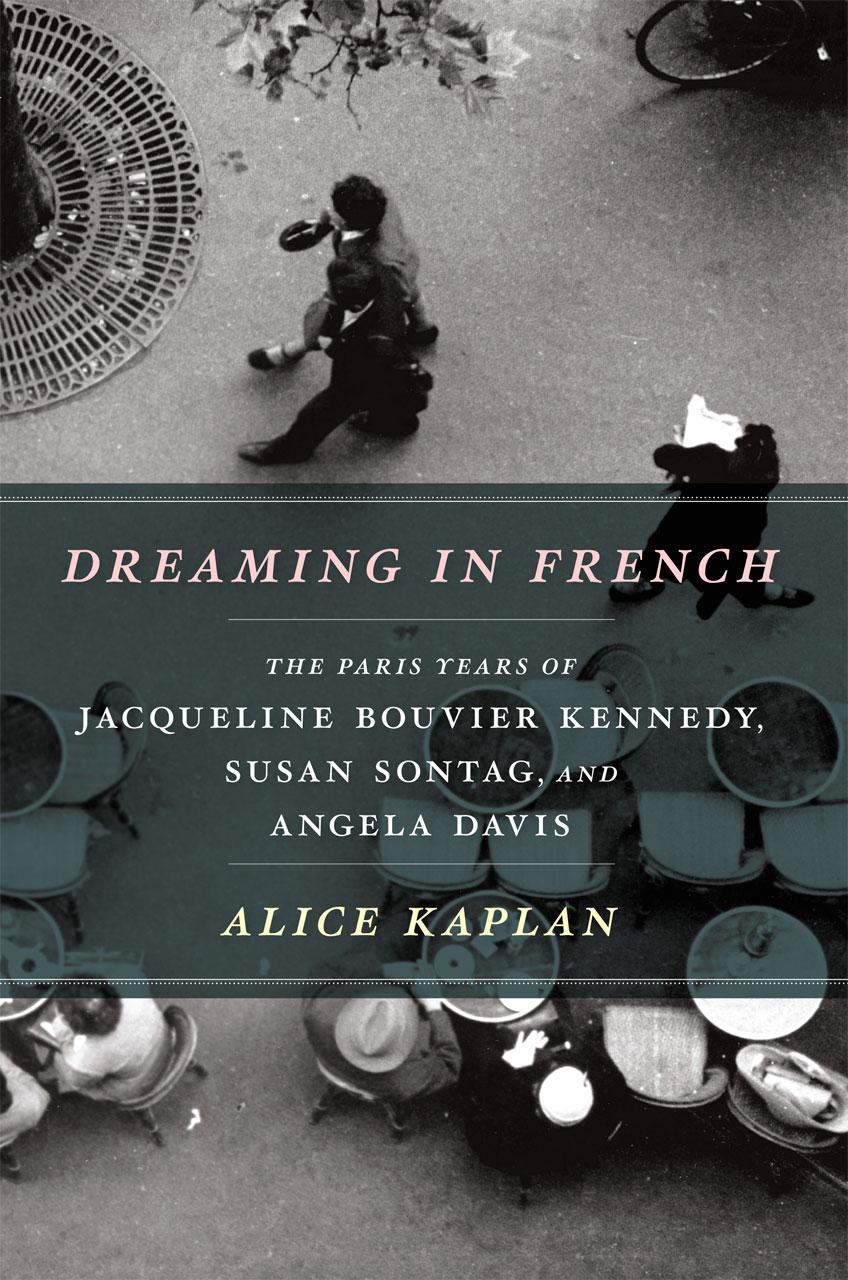

Dreaming in French: The Paris Years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis

Dreaming in French: The Paris Years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis

by Alice Kaplan

University of Chicago Press

272 pages, $26.

WHEN international travel for civilians again became possible after World War II and study abroad programs resumed, there was a flood of students who leapt at the chance to immerse themselves in French culture. Three women who did so were Jacqueline Bouvier, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis, each of whom would go on to be very famous, and each a “gay icon” in some sense, whether by her own erotic orientation or by her reputation in the GLBT world.

Having gone to France myself in June, 1948 (a year before an eighteen-year-old Jackie Bouvier made the trip), I feel a special kinship with anyone who experienced this rite of passage. On my converted troop ship—ocean liners were in short supply this soon after the war—I met quite a number of passengers, but not many were college students enrolled in academic programs abroad. There were a lot of folk-dancing ethnics returning to the countries from which they had fled, and the rest were mostly people going on their own to experience newly liberated Europe. Or they were would-be artists like me going to Paris to become poets and painters—we were the bohemian contingent.