IT WAS 1:30 A.M. when I entered the absolutely highest bid I was willing to make and held my breath. Everyone who has ever had an eBay moment can empathize. Surely every other gay book collector in the world was after this scarce title, and I could only wonder how rich they were. But in a moment the screen was flashing and I was screaming to my partner, “Paul, I’ve won! I’ve won!” Copy #116 of Edward Prime-Stevenson’s The Intersexes: A History of Similisexualism as a Problem in Social Life was mine.

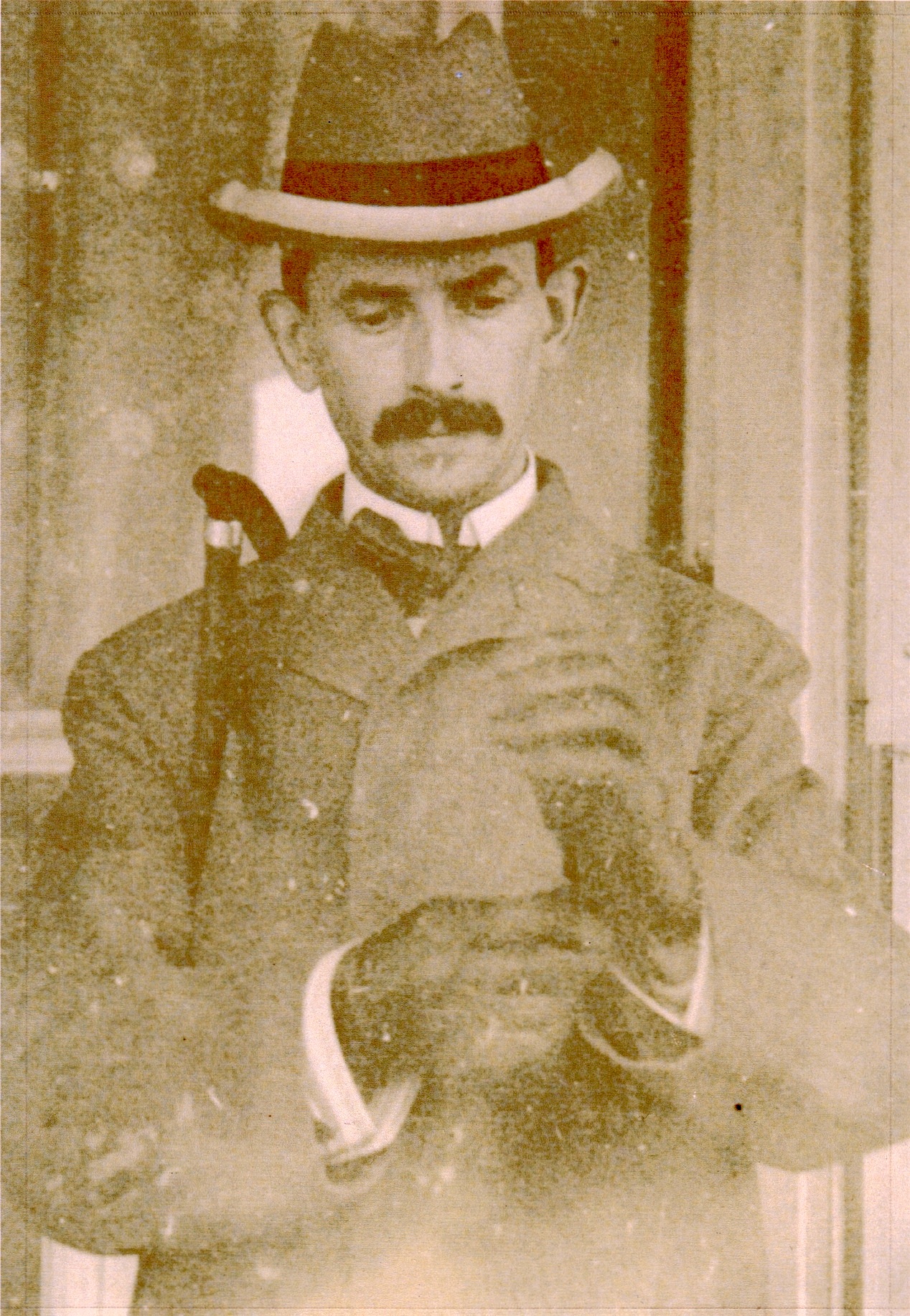

Edward Irenaeus Prime-Stevenson (1858–1942), although known to a few gay scholars, is not exactly a household name. This is not surprising, if only because he always hid behind a pseudonym when writing his gay-themed works. He also lied about his age and enjoyed hoodwinking an audience whenever he could. More to the point, his works are to this day not easy to find. The general outlines of his life are established, though details are hard to come by. Born in Madison, New Jersey, he was modestly known in his day as a music critic and writer of fiction and poetry. In mid-career, he abandoned all this and fled to Europe, where he wrote two classics in gay literature, Imre and The Intersexes. He died largely unknown in a Lausanne hotel with a carton of unpublished works in tow. Rediscovered in the 1950’s by Noel I. Grade (Edgar Leoni), who referred to him as “the father of modern homosexual literature,” Stevenson remains more skeletal than a fleshed-out literary figure.