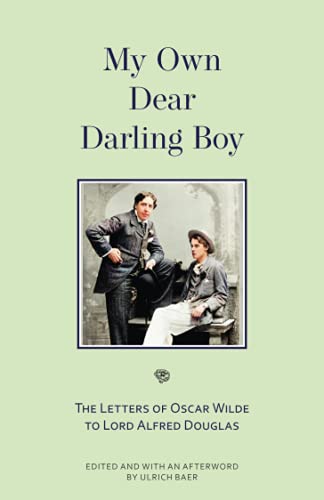

MY OWN DEAR DARLING BOY

MY OWN DEAR DARLING BOY

The Letters of Oscar Wilde to Lord Alfred Douglas

Edited by Ulrich Baer

Warbler Press. 140 pages, $12.95

WHEN OSCAR WILDE met Lord Alfred Douglas—“Bosie”—in 1891, Wilde was a married father, and he was already a popular playwright, a poet, a wit, and a dandy. Bosie was a 21-year-old undergraduate, and it seems indisputable that Wilde had considerable influence on him. In his own self-defense during his suit against the Marquess of Queensbury, Wilde referred to an ancient Athenian tradition in which worldly older men chose unschooled male youths to be their protégés. It was a mutually beneficial relationship that involved scholastic and military education in exchange for help and service, possibly sexual service, on the part of the younger man.

The inequality between Wilde and his “darling boy,” as well as the status of this relationship as part of a tradition, is at the heart of an ongoing discussion about what these two people meant to each other. If one of them was exploiting the other, it’s not entirely clear who was the predator and who was the victim. The extent to which Bosie was responsible for Wilde’s downfall has been debated, while the source of Wilde’s foolish decision to sue the Marquis (arrogance? blind love for Bosie? deliberate martyrdom for a cause?) has likewise come under scrutiny.

Wilde’s love letters, which span the period from 1892 to 1897 are valuable for the light they shed on his feelings for his “own dear boy.” Here is the first paragraph from a brief note: “Your sonnet is quite lovely, and it is a marvel that those rose-leaf lips of yours should have been made no less for music and song than for madness of kissing. Your slim gilt soul walks between passion and poetry. I know Hyacinthus, whom Apollo loved so madly, was you in Greek days.”

This passage places the erotic nature of the relationship beyond any doubt, and it also shows that Wilde encouraged his young lover to develop his artistic talents. Wilde seems sincere when, following the Greeks, he describes the relationship as essentially one of mentorship. In the remaining letters, most of which are surprisingly brief, mundane plans for future trips and news about mutual friends appear alongside praise for Bosie’s charms. In the summer of 1894, Wilde wrote: “Dear, dear boy—you are more to me than any one of them has any idea—You are the atmosphere of beauty through which I see life—you are the incarnation of all lovely things—When we are out of tune—all colour goes from things for me—but we are never really out of tune—I think of you day and night.”

The letters show only one side of the relationship (we don’t have Bosie’s replies), but several of them refer to letters that Wilde received from Bosie, among other items. Wilde avoids mentioning his wife and two sons, and even when he refers to “any of them”—other people he knew—there is an implication that Wilde sees his relationship with Bosie as something to be kept apart from the rest of their lives, a shelter from the philistine world. Much of the poignancy of these letters comes from a modern reader’s knowledge of the public scandal that neither could foresee before 1895, and which they both struggled to understand afterwards.

About half of this book consists of a timeline of events in Wilde’s life and the editor’s explanation of how these letters turned up at an auction in New York in 1920, where they were sold and then resold to several bibliophiles. An essay by one of these collectors is also included. In “Letters that We Ought to Burn,” A. S. W. Rosenbach ironically suggests that love letters in general should not outlast the people who wrote them because no one else has a right to read them, or an ability to understand them out of context. Be that as it may, Oscar Wilde’s private messages to Bosie appeal to the voyeur in everyone who reads biographies of the unforgotten dead.

Jean Roberta is a widely published writer based in Regina, Saskatchewan.