LEAVE IT to director John Waters to succinctly capture why film scholar and critic B. Ruby Rich is such a pleasure to read: “Ruby Rich has to be the friendliest yet toughest voice of international Queerdom writing today. She’s sane, funny, well-traveled, and her æsthetics go beyond dyke correctness into a whole new world of fag-friendly feminist film fanaticism.”

In an influential 1992 essay in The Village Voice, Rich coined the term “New Queer Cinema” to label what she saw as a new cinematic phenomenon, arising in the mid-1980s as a result of a technological advance, affordable high-quality camcorders, along with widespread outrage over the AIDS epidemic and the government’s disastrous response to that crisis. Soon the term expanded to encompass a whole generation of queer filmmakers, artists, and even like-minded political activists.

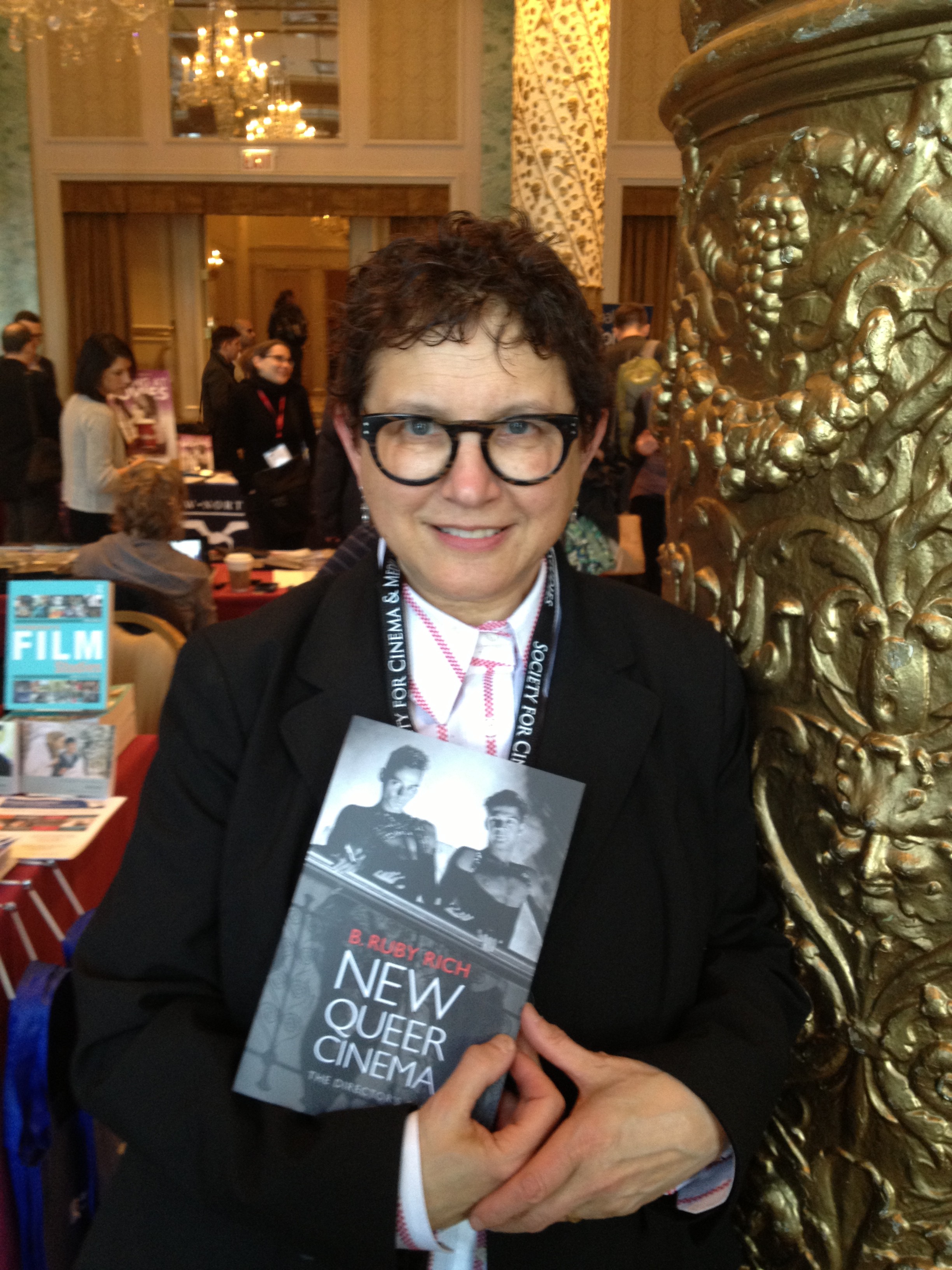

Ms. Rich’s most recent book, titled New Queer Cinema: The Director’s Cut (Duke University Press, 2013), reflects her interest in this phenomenon. It’s a collection of her writings from her initial piece in the Voice to the present. Reading it is like binge-watching your way through a history of modern gay cinema. Throughout the essays, Rich implores avant-garde filmmakers to cultivate an audience and then challenge its expectations: “I was troubled by a pronounced audience tendency: the desire for something predictable and familiar up there on-screen, a sort of Classic Coke for the queer generation, not the boundary-busting work that I cared about and wanted to see proliferate.”

Ms. Rich’s most recent book, titled New Queer Cinema: The Director’s Cut (Duke University Press, 2013), reflects her interest in this phenomenon. It’s a collection of her writings from her initial piece in the Voice to the present. Reading it is like binge-watching your way through a history of modern gay cinema. Throughout the essays, Rich implores avant-garde filmmakers to cultivate an audience and then challenge its expectations: “I was troubled by a pronounced audience tendency: the desire for something predictable and familiar up there on-screen, a sort of Classic Coke for the queer generation, not the boundary-busting work that I cared about and wanted to see proliferate.”

Ruby Rich is a professor of film and digital media at the University of California, Santa Cruz. She has also taught documentary film and queer studies at UC-Berkeley. Rich has been a regular contributor to The Village Voice and the British Film Institute’s Sight & Sound. She currently serves as the editor of the magazine Film Quarterly. Her 1998 book Chick Flicks: Theories and Memories of the Feminist Film Movement (Duke) is considered a definitive collection of essays on the origins and development of feminist films.

I spoke with Rich in San Francisco on Pride Sunday in late June—which is also the final day of the City’s Frameline lgbtq film festival—about current trends in queer cinema.