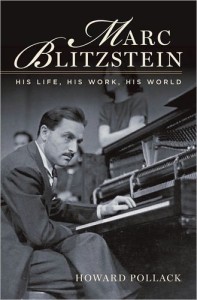

Marc Blitzstein: His Life, His Work, His World

Marc Blitzstein: His Life, His Work, His World

by Howard Pollack

Oxford University Press. 618 pages, $39.95

GROWING UP in a leftist family in the 1950s, my cultural education included lectures given by my mother on the connection between politics and the arts. She would tell me of her experiences as a young socialist during the 1930s attending politi- cal theater in New York City. Her favorite socially conscious composer was Marc Blitzstein. Howard Pollack, professor of music at the University of Houston, has written a comprehensive biography that opens a window onto the creative genius of Blitzstein while offering a thorough study of his innovative music.

Marcus Samuel Blitzstein, born in Philadelphia in 1905, was (among other things) a Jew, a homosexual, and a member of the Communist Party from 1938 to 1949. In 1964, while on vaca- tion in Martinique, he died from complications resulting from a gay bashing. His most famous work, The Cradle Will Rock (1937), is a scathing indictment of the capitalist system. Blitzstein was encouraged along these lines by Bertolt Brecht, who once told him: “there is prostitution for gain in so many walks of life: the artist, the preacher, the doctor, the lawyer, the newspaper editor.”

This musical drama had a spectacular premier. Directed by Orson Welles, produced by John Houseman, and funded by the Federal Theater Project, Cradle’s opening was embroiled in po- litical controversy. As a result of budget cuts for the Federal Theater project, the actors and workers were fired and the the- ater shut down. Then there were complications when the actors’ and musicians’ unions would not allow its members to partici- pate in the production. In defiance of all this, Welles came up with a plan: all the actors would go to a new venue (the Venice Theater) as audience members and perform their roles from the house. There were no sets, no lighting, nothing. Blitzstein at the piano and an accordion player comprised the entire orchestra. By the end of the evening, the audience went wild, Blitzstein was an overnight hero, and The Cradle Will Rock became a the- atrical event.

Pollack goes into great depth about all of Blitzstein’s com- pleted and uncompleted works. There are extensive chapters de- voted to the making of Regina (a 1949 adaptation of Lillian Hellman’s The Little Foxes), Reuben, Reuben (a 1955 musical drama based on Goethe’s Faust), and Juno (1959, based on Sean O’Casey’s, Juno and the Paycock). Also discussed at length is Blitzstein’s long-term association with Kurt Weill and The Threepenny Opera. Blitzstein was responsible for the suc- cessful musical adaptation of the Weill work, which opened in 1954 and ran for several years. Blitzstein’s only hit song was his musical interpretation of “Mack the Knife.”

Pollack’s main focus is Blitzstein’s mu- sical biography, though he doesn’t neglect his subject’s personal life. Blitzstein seems to have known just about everyone in the music world of the 20th century: Nadia Boulanger, Arnold Schoenberg, Aaron Copland, Ned Rorem, Virgil Thomson, Lotte Lenya, Kurt Weill, and on and on. Leonard Bernstein was the godfather to his children. Delving deeper into Blitzstein’s personal life, Pollack explores his relationships with Eva Gold- beck and with his male partners. He became involved with Goldbeck in the early 1930s, and they were married in 1933. Although Blitzstein was primarily homosexual, Eva played a significant role in his emotional and creative life. She died in 1936 of complications from anorexia nervosa, and he was dev- astated by this loss.

Blitzstein had many male lovers and referred to his cruising as “excursions on the quest.” While serving in London during World War II, he had a two-year romance with William Hewitt. In 1961, in Rome, he had an affair with Adolfo Valletri.

The biggest surprise for me was learning that Eve Arden of Our Miss Brooks, the 1950s TV sitcom heartthrob, got her start singing “Send in the Militia” (1932) in Marc Blitzstein’s pro- duction of Parade. The second surprise involved Nelson

Eddy—of the team of Nelson Eddy and Jeanette MacDonald, stars of the Hollywood operettas Rosemarie (1936), Maytime (1937) and other equally saccharine productions of the Depres- sion Era. Eddy, at the start of his career in 1928, sang two of Blitzstein’s songs (with the composer at the piano) at a concert in Philadelphia.

Another surprise is to realize how relevant Blitzstein’s vi- sion is today. He wanted to use music as a vehicle to awaken so- cial consciousness. He wanted his music to reach not just a select few but everyone. Like Aaron Copland, Martha Graham, John Steinbeck, and others—members of what was known in the 1930s as “the popular front”—he wanted to throw over “art for art’s sake” and create a culture that could bridge the gap be- tween artist and audience and speak to everyone, regardless of background.

One of Blitzstein’s final projects, commissioned by the Met- ropolitan Opera, was a work based on the Sacco and Vanzetti case of 1927. The Italian immigrants Nicola Sacco and Bar- tolomeo Vanzetti were convicted of murdering two men during an armed robbery at a shoe factory in 1920. After many appeals, they were unjustly executed on August 23, 1927. Many on the Left felt that they had been convicted and executed because of their anarchist politics. Blitzstein had been thinking about writ- ing the opera since the 1930s. He wrote a choral work, The Con- demned (1932), on the same theme. The case continued to haunt him until the end of his life. Unfortunately, he was murdered before he could complete the full-length opera.

In this post-Occupy Wall Street time, we await the emer- gence of new forms of cultural critique that will inform the arts. Blitzstein used his prodigious gifts in service of producing music designed to awaken people to the abuses of an exploita- tive economic system. He hoped that his message would inspire people to take back their government and their lives. We live in a time when such encouragement is sorely needed. In 1962, in a lecture, Blitzstein commented on what he termed “the crucial questions of the day”: “the one thing I can ask is that our lives have some meaning.”

Irene Javors, a psychotherapist based in New York, is the author of Culture Notes: Essays on Sane Living.