IF YOUR ACQUAINTANCE with Sodom and Gomorrah were limited to what you see in movies, your impression might differ only slightly from the story in Genesis 19. That’s because the biblical version is already as farfetched as the script of a Hollywood epic, and also because Hollywood and the Bible have a great deal in common, to wit:

- Both operate from a vast root system of mythology that extends in a thousand directions.

- They are both replete with a large body of stories, many unforgettable and others lame or pointless.

- The Bible, like the movies, contains a number of genres: morality tales, adventure, family drama, fables, royal and dynastic chronicles, musicals (e.g., the Psalms), romances, disasters, sci-fi, biographies, epics, war stories, and so on.

- Among the colorful, indelible characters in movies and in the Bible are heroes, villains, harlots, tricksters, murderers and their victims, monsters, musicians, kings, queens, slaves, wise and foolish men and women, warriors, peacemakers, and so on.

- In the Bible, stories end well when characters obey Yahweh. In pre-1960s Hollywood pictures, stories typically had happy endings when characters adhered to American middle-class values: monogamous heterosexuality, maintenance of strong family ties, patriotism, respect for mainstream religion, crimes suitably punished, a place for women and minorities which they instinctively knew and stayed in.

- The Bible, like Hollywood, is populated by a lot of Jewish people.

§

It took almost three decades following the invention of motion pictures for Sodom and Gomorrah to reach the silver screen, a surprising fact if you recall the new medium’s zest for titillation. It’s less surprising, however, when you consider what a forbidden topic this tale really was, even in the early years of Modernism. Throughout the opening decades of the 20th century, the very phrase “Sodom and Gomorrah” was code for unspeakable pleasures.

Europe was braver than the U.S. In 1922, a Hungarian director working in Vienna dared to make a film titled Sodom und Gomorrha. It cost so much to produce that to this day it remains Austria’s most expensive film (allowing for inflation). Long unseen but now on DVD, the picture’s gigantism shows the influence of D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) and other cinematic behemoths. Mihály Kertész, the director of Sodom und Gomorrha, came to Hollywood a few years later and, as Michael Curtiz, directed such classics as Casablanca and Mildred Pierce.

Europe was braver than the U.S. In 1922, a Hungarian director working in Vienna dared to make a film titled Sodom und Gomorrha. It cost so much to produce that to this day it remains Austria’s most expensive film (allowing for inflation). Long unseen but now on DVD, the picture’s gigantism shows the influence of D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) and other cinematic behemoths. Mihály Kertész, the director of Sodom und Gomorrha, came to Hollywood a few years later and, as Michael Curtiz, directed such classics as Casablanca and Mildred Pierce.

Sodom und Gomorrha opened on October 13, 1922, in Vienna, with a running time of about three hours. What remains today, however, is a restored print roughly half the length of the original, at 95 minutes. The restoration of this odd masterpiece represents a cinematic marvel, for until the 1980s only fragments were known to exist. Film scholars eventually discovered additional footage of varying lengths in Berlin, Prague, and elsewhere. The film that they pieced together offers a vivid impression of the whole from its surviving parts. Any statements made now, however, refer to those salvaged parts and not, of course, to the original whole. In this respect, Sodom und Gomorrha jibes with its source material, for in its dishevelment it has as many jumps and gaps as does the gimcrack story in Genesis 19.

As in many early silent films, a modern-day framing story wraps around the ancient one. Sodom und Gomorrha, however, has an even more complex structure: three subsidiary stories are embedded within the main one. This scenario competes with the most outlandish opera plots, and anyone viewing these cinematic remains of Sodom und Gomorrha will surely need a guide. For that reason, I offer a brief synopsis.

Although the tale is set in London, the buildings, streets, and gardens look Viennese. In “London,” then, young Mary Conway becomes the fiancée of Jackson Harber, a wealthy, unscrupulous capitalist more than twice her age. Earlier he was the lover of Mary’s mother, an aging flesh-peddler who forced Mary to desert her true love, the sculptor Harry Lighton. In a studio as grandiose as a museum gallery, Harry is just finishing a monumental sculpture that rises twenty feet or more. It is a likeness of Mary. The newspapers have dubbed the work “Sodom—a Symbol of Beauty and Sin.”

Jilted, Harry attempts suicide and is rushed to hospital. Mary, devastated, gives herself up to a life of debauchery. She joins the revels at her fiancé’s vast estate, where Harber lives like a Teutonic Jay Gatsby in a Hapsburg palace near the Vienna woods. Hundreds attend his louche parties, where countless dancers, male and female, move in stiff straight lines, then weave through the forest with arms raised like celebrants around a maypole. Eventually the dancers regroup in militaristic rows, which suggest a mix of Leni Riefenstahl and Busby Berkeley—at low points of their respective careers.

Harber’s son Edward returns from university accompanied by his tutor, a handsome priest. Mary zooms in on the youth. But one man is not enough. She lures both father and son to an assignation in an outlying summerhouse on the estate. While waiting for them, she falls asleep and into a Freudian dream sequence, which takes us into the first story-within-a-story. Mary dreams that her fiancé and his son fight over her, which she finds arousing. The son stabs the father. Meanwhile, still dreaming, she vamps the priest, who denounces her sins even as heat builds beneath his clerical robes.

In the dream, she denounces Edward to the police as the one who killed his father, but the priest in turn denounces her. This dream then morphs from Freudian Vienna into an Expressionist prison sequence heavily influenced by The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920). When the priest, in this second dream-within-a-dream, visits her cell to comfort her before she is hanged, she tries again to seduce him. Struggling to resist her blandishments, he condemns her as “You daughter of Sodom!” This denunciation pushes her into the third dream, viz., the Sodom sequence, which runs for half an hour, or one-third of the restored film.

When Norma Desmond wrote the demented script of her Salome, which she imagined would return her to stardom, she surely had in mind something like the last half-hour of Sodom and Gomorrha. In place of DeMille, she might have proclaimed, “I think I’ll have Curtiz direct it!” For with Sodom und Gomorrha he had already filmed one of the prodigious follies of the silent screen.

In Mary Conway’s third dream, she is Lot’s wife. But dream becomes nightmare at the end when she turns into a pillar of salt. Despite that familiar climax, this storyline adheres but loosely to the biblical one. Curtiz makes Lot’s wife a priestess of Astarte, the Near Eastern goddess of fertility, sexuality, and war. (The ancient world also knew this goddess as Ishtar.) In this context, the word “priestess” is a euphemism; the real term was “temple prostitute.” And the director signals the woman’s true calling: she is surrounded by panting young men who pass her around in preparation for their clergy-feast.

When an angel arrives in Sodom, it’s not the handsome boys of the town who surround Lot’s house to get at the stranger. The young are at frenzied worship in Astarte’s temple. Rather, it’s the rough-hewn old men who start a feeding frenzy. These codgers could be the Three Stooges—or rather, the Three Thousand Stooges, for that’s the number of wizened, leathery extras who swarm the streets of Sodom to crash Lot’s living room (whose design and ornamentation reflect Vienna Secession style.)

Meanwhile, back at the temple, orgies are in progress. The temple is one of the grandest movie sets ever constructed. Rising ten stories or higher, it towers like a pyramid. Teeming worshipers throng the great stairways. Others man the parapets, and battalions of soldiers on the ground turn it into a human anthill. When revelers convey a towering statue of Astarte into the square before the temple, the grandiosity of the scene recalls Elizabeth Taylor’s Cleopatra triumphantly entering Rome. Sources differ as to the number of people who worked on Sodom und Gomorrha, some claiming 3,000 and others as many as 14,000.

The unyielding angel is brought to Astarte’s temple and tied to a post for burning. Lot’s wife, bejeweled and plumed like a Ziegfeld showgirl, taunts the captive: “If you’re an angel, prove it to me.” She lights the fire, but then—suddenly the angel, unfettered, is standing in the center of town. The crowd has vanished. Sodom combusts. Now Sodom is a war zone. Firebombing, strafing, earthquakes rip the city like flimsy fabric. Lot darts into Astarte’s burning temple, grabs his wife, and rushes with her and the angel out of the city gates.

From the angel comes a familiar warning: Don’t look back! But the woman disobeys. Even as she turns, her body is transformed. She is pure at last: white and svelte. Lot, in his grief, caresses her saline breasts and falls to his knees before her. Quickly, the angel leads him away. This dream ended, we are back in the prison cell with Mary and the priest. She is led struggling to the scaffold. But that too is only a dream. Mary awakens in her summerhouse bed. “In one-half hour I lived through a frightful tragedy,” she pants. The antidote is virtue. The film ends with Mary reunited in the hospital with her one true love, the sculptor.

§

The next cinematic trip to Sodom and Gomorrah occurred in 1932, in a film that may now be lost. No one, apparently, has actually seen The Sacrifice of Isaac, although The New York Times headlined shortly before the scheduled New York premiere: “Yiddish Talking Picture on View Here Tuesday.” The article names the film as “the first Yiddish talking picture, in which the story of Sodom and Gomorrah is also found.” But Eric Goldman, in his 1980 book A World History of the Yiddish Cinema, makes no mention of The Sacrifice of Isaac.

§

It was in Rochester, New York, not Hollywood, that the first American film was made on the subject of Sodom and Gomorrah. This was Lot in Sodom, an independent short made in 1933, with a running time of 26 minutes. This fey and affected visual poem—a minor epic of sorts, although for its makers more endgame than forecast—has gained cult status in recent years. The experimental filmmakers who made Lot in Sodom, James Sibley Watson, Jr. (1894–1982) and Melville Webber (1871–1947) came late to filmmaking, and departed soon after. Their combined output runs for less than one hour, the longest of their works being Lot in Sodom.

Watson, an heir to Western Union money, was born in New York. At Harvard, he made friends with e. e. cummings. In later years, Watson and his wife Hildegarde—who appears as Lot’s wife in the film—became enthusiastic supporters of cummings and other poets, including Marianne Moore. Not content with a life of leisure, Watson earned a medical degree, though philanthropy and the arts, rather than medicine, seem to have commanded his attention. In 1920 he purchased The Dial, an influential literary magazine that continued publication until 1929.

In the late twenties, Watson became interested in the artistic possibilities of film, and in 1928 he and Melville Webber collaborated on “The Fall of the House of Usher,” an elliptical thirteen-minute variation on the story by Edgar Allen Poe. They worked on a second short film—this one an odd seven-minute scrap called “Tomato’s Another Day”—in 1930, ending their collaboration and their respective film work three years later with Lot in Sodom. This final Watson and Webber collaboration, self-consciously “artistic,” exceeds much Hollywood product of the time in technical virtuosity. And it’s certainly more daring, with male and female nudity that even pre-code studio pictures wouldn’t risk. The film opens literally in the clouds above Sodom, followed by an early instance of a split-screen image. This one is bisected by a stylized vertical lightning flash akin to the most aggressive Op Art.

The first location shot is from above, an angel’s-eye view of Sodom. Using a scale model village with a towering temple in the center, Watson and Webber minimized the town that Michael Curtiz, and later filmmakers, couldn’t resist exaggerating. Does the temple honor Yahweh or Sodom’s deities? Impossible to tell, for the film now takes on the lineaments of a dream: a balletic, cubistic, expressionistic, phallic dream.

Avant-garde and oneiric, the film simultaneously follows and fragments the familiar plot. Young, bare-chested male dancers perform a stylized ballet orgy in a steamy space like a bath house. This cavorting, of course, represents “wickedness,” although with a long wink of approval. The dancers, added to the other cast members, total about two dozen. That number, along with high-gloss production values, sets Lot in Sodom apart from the usual happy-hands-at-home experimental film.

Not everyone is beautiful at the ballet: some of the dancers are hairy and goat-like. The real old goat, however, is Lot, who starts out a dreary puritan spoilsport chanting psalms while everyone else in town is having a pagan good time. Then Lot’s wife appears in Martha Graham costume. Her movements also derive from Graham. When the beautiful black-hooded angel appears, the boys dance around him in a frenzy. Word spreads that he’s quite a looker, and from that point on, men fill the street outside Lot’s house. (Lot in Sodom shows the marked influence of Jean Cocteau’s The Blood of a Poet from 1932. Ironically, it’s more homoerotic than Cocteau’s film.)

Lot offers his daughter to the mob; they howl with laughter. Then Lot himself takes a look at the daughter, who strips for her father. He pants with lust. When a big snake appears, it’s a game of hide-and-symbol. Time-lapse passionflowers begin to blossom. They keep on opening—imagery perhaps borrowed from Georgia O’Keeffe’s paintings—until the screen fills with enough vaginal imagery to start not a movie monologue but a postmodern conference.

Spring water trickling over a pair of hands announces that Lot’s daughter’s water has broken, and a newborn babe appears. Lot beams and dotes on his—child, or grandchild? In a clever swerve from the Bible story, there’s a hint that the angel might have fathered the infant. Nevertheless, he commands Lot’s family to leave Sodom. Lot and his daughter rush out arm in arm—where is the baby?—while the wife dawdles. Only later does she follow at a distance as flames lap the city from below and brimstone strikes it from above. Lot’s wife makes her final Martha Graham movements as she turns into a salty phallic menhir.

In 2000, Watson and Webber’s less significant The Fall of the House of Usher was added to the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress. This choice is ironic, though not surprising. A look at the list of feature films, documentaries, and newsreels chosen for the list since its establishment in 1989 suggests that safety, rather than aesthetics, comes first. And a picture like Lot in Sodom might infuriate the ghost of Jesse Helms. That’s because this subversive little film not only glamorizes the Sodomites, it also doesn’t kiss anyone’s holy book. In D.C., that’s the real sin. To survive in U.S. politics, you’d better know just where to kiss.

§

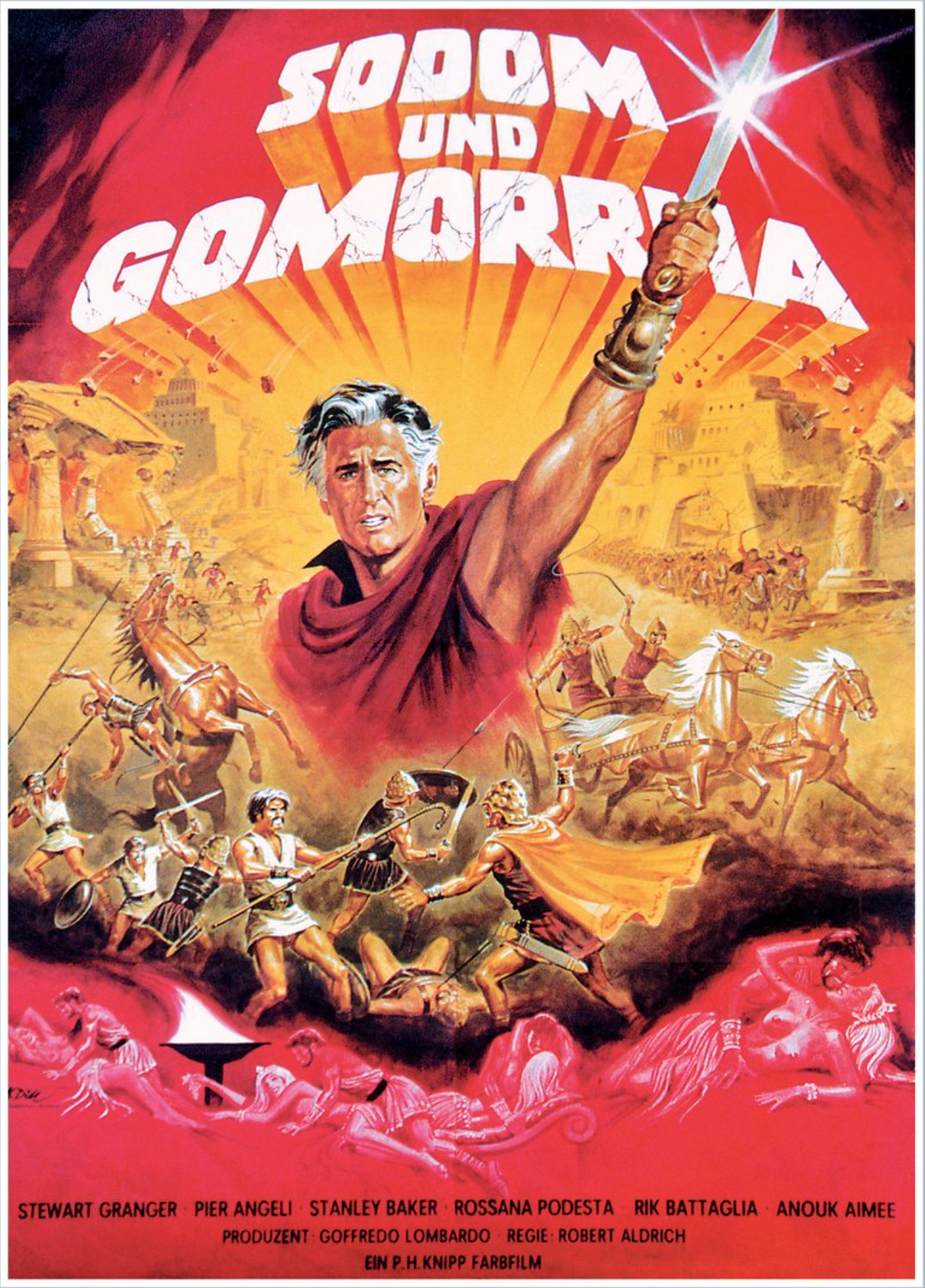

Hollywood didn’t get around to making a movie of Sodom and Gomorrah until 1962, when Robert Aldrich made a film whose title was none other than Sodom and Gomorrah. But Hollywood had waited too long. Ten years earlier, the picture might have earned the routine respect accorded wide-screen biblical epics. Perhaps it would have trumped Caligula. However, with the widespread censorship of all Hollywood films under the Production Code and the absolute prohibition of anything resembling homosexuality, no studio would have dared to release a film with such an incendiary title as Sodom and Gomorrah in the 1950s. Perhaps an added reason for avoiding such a film was that Hollywood itself was often accused of out-sinning the doomed Cities of the Plain.

Aldrich sprinkled his picture with peekaboo sex—homo, hetero, incest, S&M—while keeping Lot’s upright Hebrews as clean as the PTA. Slavery is the chief sin here: slaves toil in the salt mines to produce Sodom’s wealth. Torture, also, is rampant, often as postprandial amusement in the royal palace. Anouk Aimée plays Bera, Queen of Sodom, a hard-faced bisexual who comes on to her brother as well as every toothsome belly dancer in the Sodom chorus line. “Hebrews and Sodomites, greetings!” proclaims Queen Bera in Joan Crawford tones when Lot and his Amish-looking entourage migrate to the great walled city. Later, these monotheists having been assimilated, she congratulates their leader as though inducting him into a hall of fame: “You are a true Sodomite, Lot.”

“I think every director wants to make one biblical spectacle,” Aldrich told an interviewer. His was one of the last to lumber out of a Hollywood studio. It takes odd liberties with the source material (Lot’s wife, for example, is the ex-girlfriend of Sodom’s queen). Stewart Granger plays Lot like a suburban Little League manager whose team of Hebrew elders has Yahweh as its sponsor. His daughters—Rossana Podestà and Claudia Mori—might have been on loan from Russ Meyer, for they have a penchant for slinky outfits and rendezvous in the bulrushes with Sodomite soldiers. Even for a director of Aldrich’s versatility, Sodom and Gomorrah was an aberration. He was surely more at home with the black-and-white decadence of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? and Hush, Hush, Sweet Charlotte.

§

To mix a metaphor, Robert Aldrich was the bellwether who opened the biblical floodgates. In 1966, John Huston directed The Bible: In the Beginning, a piece of kitsch suitable for a creationist theme park. He begins with Adam and Eve, progresses to Cain’s murder of his brother Abel, and then Huston himself hams it up as Noah in a 45-minute sequence that includes an ark full of squawking animals in need of Dr. Doolittle. This is followed by the familiar story of Abraham (George C. Scott) and Sarah (Ava Gardner), with a side trip to Sodom and Gomorrah and a sanctimonious finale when Abraham draws his knife to sacrifice Isaac, a killing that is halted, not by an angel, but by the voice of Yahweh himself.

As the angels (all three played by a rather shopworn Peter O’Toole) troll the streets of Sodom, coital grunts emanate from behind dark walls. Every thoroughfare is a prehistoric Christopher Street full of cruising queens who leer and smack their lips. Inside Lot’s house, the angels gain another fan. One daughter declaims, licking her chops: “So fair they are, so fair!” Then the mob appears. Looking ready for Halloween on Castro Street, they break down the gates of Lot’s courtyard. Preening and lisping, they demand, “Bring them out that we may knooow them!” Their eye shadow suggests Elizabeth Taylor’s Cleopatra in the movie released three years earlier.

The sins of Sodom, whether heterosexual or gay, are Hollywood pagan: a woman kneels to pleasure a goat that’s dyed blue and crowned with a golden headdress. As the prissy twin angels continue their tour, drag queens pour into the street as if auditioning for RuPaul’s Drag Race. Lot’s wife (played by the glamorous Italian star Eleanora Rossi Drago) turns her head, as expected. The last thing she beholds is a Cold War mushroom cloud over her city.

§

In 1975, the 26-year-old Spanish director Pedro Almodóvar made a ten-minute underground film titled “The Fall of Sodom.” Francisco Franco, dictator of Spain for almost four decades, died that same year, and the country’s fascist, puritanical police state began to crumble. A year earlier, Almodóvar had made another ten-minute film called “Two Whores, or Love Story Ending in a Wedding.” Almodóvar’s early films are as subversive as those of his American contemporary John Waters. It’s almost to be expected, then, that “The Fall of Sodom” laughs in the face of Spanish institutions—the family, the church, middle-class propriety—and Hollywood as well. As Lot and his family flee the city, his wife turns back and changes into a statue of salt. Lot, realizing that she has lagged behind and skeptical of the angels’ warning, goes back to look for her. In Almodóvar’s sardonic comment on the equality of the sexes, Lot too becomes a salty white pillar. The two daughters, terrified of what may happen to them if they go in search of their parents, nevertheless do so—except they walk backward with heads unturned. Their discovery terrifies them further. They dash off and take refuge in a cavern. Alone and horny, they regret the absence of their father. “He would have fucked us,” they lament, “and we could have borne sons by him who would then have begotten glorious generations.”

But these girls are no longer figures out of the Bible. They are figures in late 20th-century Spain. Nothing happens; their future is a sterile blank. This is Almodóvar’s assessment of the country’s stagnation during the years of Franco’s dictatorship. Had Franco lived on, Almodóvar, too, would undoubtedly have found himself as a block of salt.

Sam Staggs’ books on Hollywood include All About All About Eve (2001), Close-up on Sunset Boulevard (2002), and When Blanche Met Brando (2006). His latest book (yet unpublished), from which this piece is excerpted and adapted, is titled Beautiful Downtown Sodom.