Beautiful Untrue Things: Forging Oscar Wilde’s Extraordinary Afterlife

Beautiful Untrue Things: Forging Oscar Wilde’s Extraordinary Afterlife

by Gregory Mackie

U. of Toronto Press. 304 pages, $80.

“LYING AND POETRY are arts. They require the most careful study, the most disinterested devotion,” declares the character Vivian in Oscar Wilde’s well-known dialogue “The Decay of Lying.” Vivian, a stand-in for Wilde, argues against the need to tether art to facts: “There is such a thing as robbing a story of its reality by trying to make it too true,” he contends, “if something cannot be done to check, or at least to modify, our monstrous worship of facts, Art will become sterile, and beauty will pass away from the land.”

“The Decay of Lying” was as much a critique of the realism of Victorian literature as it was an argument for the pleasure of artifice in art. For Vivian, the beauty of artifice was precisely what gave art its power. But what of the artist himself? What becomes of literary forgeries, imitations, and outright faked manuscripts when we consider Wilde’s notion of art’s beautiful lies?

This is the question that Gregory Mackie takes up in his deeply researched and entertaining book Beautiful Untrue Things: Forging Oscar Wilde’s Extraordinary Afterlife, which looks at how Wilde’s reputation was recovered and exploited in the decades following his death—specifically in the 1920s, when the writer enjoyed a revival. Mackie’s intention is not to confirm the authentic and original works against the purported forgeries. Instead, he seeks in his words “to illuminate the cultural work done by the rich signifying power of Wilde’s name in the literary marketplace.” In this sense the book tells a story about how Wilde became “Wilde”—the creative literary figure as opposed to the notoriously disgraced homosexual of Victorian England.

The story of Wilde’s afterlife begins with a group of men who, in the early 20th century, compiled and shaped an official literary biography and reputation for the writer. Robert Ross, Wilde’s close friend and literary executor, published a fourteen-volume collected edition of Wilde’s work in 1908. Ross’ secretary, the bibliographer Christopher Millard, would publish his Bibliography of Oscar Wilde in 1914. Both men worked with the eccentric collector Walter Ledger, whose private devotion to Wilde fueled a vast archive of his published work and ephemera. While these men may have formed what Mackie terms a “homosocial enthusiasm” for Wilde, part of their recovery of the disgraced writer was to erase overt references to homosexuality in his work, most notably Ross’ editing of De Profundis as published in his Collected Works. How such efforts were a mask for their own sexuality is hinted at but not explored in the book under review. What is clear is that Ross, Millard, and Ledger were instrumental in shaping what Mackie calls the “legend of the ‘real Oscar Wilde’”—one that was washed clean of controversy and radical ideas—and in fostering Wilde’s entrance into the English literary canon.

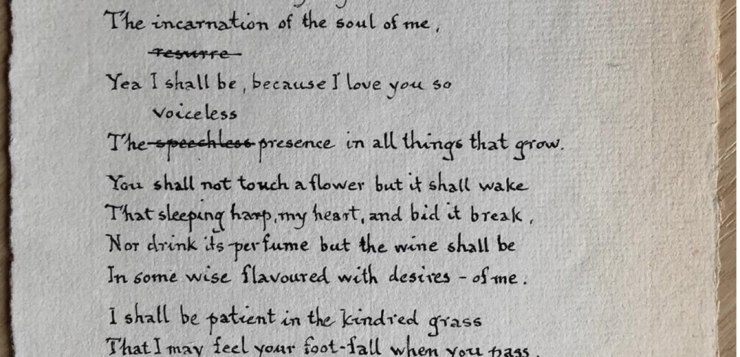

However, as Mackie shows, this enthusiasm for the “authentic” Wilde held its own form of imitation. Ledger was known to annotate and copy Wilde’s manuscripts, replicating the handwriting with exacting detail. Some of these he shared with Ross, who replied with ironic good will, noting in one letter his “powers of forgery are almost unholy.” It’s this slippery line between enthusiast and forger that anchors Mackie’s argument as he reconsiders the cultural practices of such gatekeepers as Ross, Ledger, and Millard with the more notorious literary forgeries that emerged in the 1920s.

It is in this era that we encounter the book’s more interesting characters. There’s the mysterious figure of Dorian Hope (sometimes known as Sebastian Hope, either name suggesting an homage to Wilde’s queerest work), who circulated and sold an array of autographed plays, poems, and letters in the early 1920s. Hope’s real identity remains a mystery, but his success at creating and peddling forged manuscripts to collectors is a captivating part of the book. Another is the story of Hester Travers Smith and Geraldine Cummins, both psychics who claimed to have conjured the spirit of Wilde, and who served as a conduit for his new writings over two decades after his death. Smith would later publish Psychic Messages from Oscar Wilde in 1924 documenting these “new” works of the dead writer. It was, as Mackie notes, one of the best examples of ghost writing in literary history.

For a queer writer intrigued with self-performance and the conceits of Victorian life and art, Wilde most likely would have enjoyed the many efforts at imitating and fabricating his work. In his final years, Wilde suggests in a letter that his assistant (and most likely his lover) Maurice Gilbert autographed copies of The Ballad of Reading Gaol, a prose poem that Wilde wrote in exile. By inviting “Gilbert to forge signature(s) on one of his final and most deeply personal books,” Mackie writes, “Oscar Wilde made his very signature a beautiful untrue thing.”

While Mackie recognizes the financial and criminal context of literary forgeries, he also points out how such efforts might be a kind of fan fiction in promoting the creative importance of Wilde’s work. For Ross, Millard, and Ledger, establishing the “authentic” Wilde canon (however washed of its homoerotic elements) was on a continuum with the creative and, at times, outlandish literary forgeries—each an admiration for the writer and the man.

Mackie’s analysis can at times get lost in the thicket of academic theories, but he leaves us with an intriguing idea about the creation of a literary reputation. As he notes throughout the book, those early gatekeepers were as important to crafting Wilde’s canonical status as the forgeries. Each in their own way shaped and reshaped the personal and creative afterlife of Oscar Wilde that would endure for decades to come.

James Polchin is the author of Indecent Advances: A Hidden History of True Crime and Prejudice Before Stonewall (Counterpoint) and a frequent contributor to this magazine.