Elizabeth Bishop: The North Haven Journal, 1974-1979

Elizabeth Bishop: The North Haven Journal, 1974-1979

Edited by Eleanor M. McPeck

North Haven Library, Inc. 80 pages, $18.95

WHEN I WENT to North Haven, Maine, for the first time last July, I took the same ferry service out of Rockland—possibly even the same boat—that carried Elizabeth Bishop there in 1974. Like Bishop, I found myself gripped by the island’s startling, plain beauty, complete with Queen Anne’s lace, balsam firs, a hodgepodge of wooden houses and barns, distant hills, and an encircling blue boundary of sea.

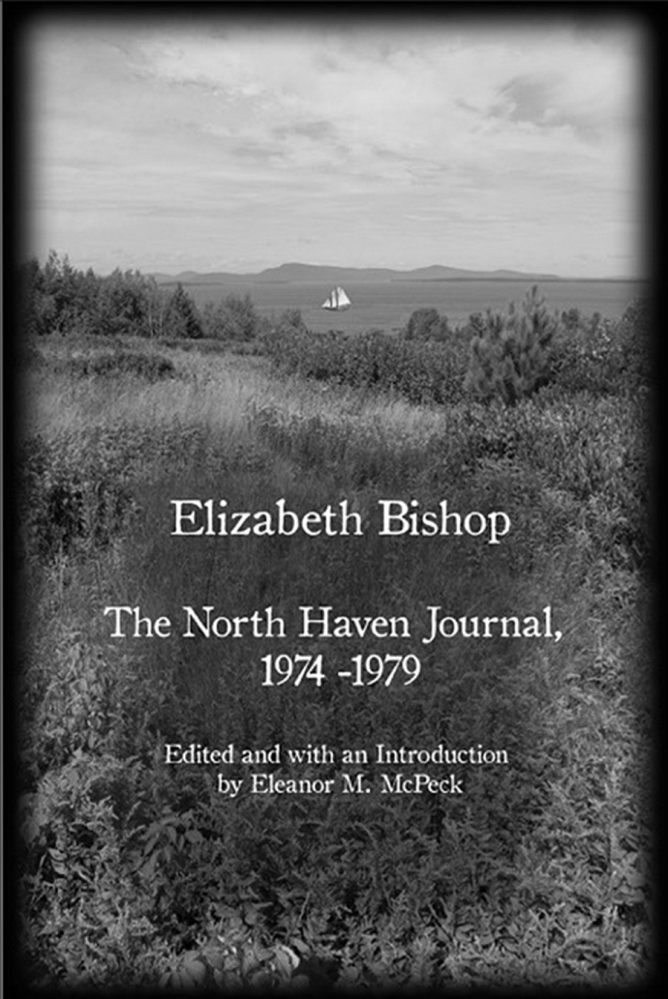

North Haven’s small library has now published the daybooks the poet kept during six summers there, providing, in the words of trustee John Storck, “a new way to meet Elizabeth Bishop.” The North Haven Journal, 1974-1979, edited by Eleanor M. McPeck, is the stunning result, faithful to Bishop’s original words (including misspellings) and hand-friendly in size. The sepia cover photo shows a view she might have had from Sabine Farm, where she stayed, while endpapers display an 1859 nautical chart of surrounding waters in Penobscot Bay.

The island reminded Bishop of Nova Scotia, where she had spent happy years as a child, and Journal entries describe wildflowers, birds, weather, and terrain common to both places. Most jottings record ordinary stuff—walks on the beach, encounters with workmen, picking loganberries to make into jam—but odder images turn up, like swimming “in seaweed,” or taking a lobster boat to nearby Vinalhaven to hear a brass quintet in dinner jackets perform in a rock quarry. When an off-island crisis intrudes—Richard Nixon’s resignation, for example, or the 1977 New York City blackout—it is quickly absorbed by a sense of seclusion and peace (no mention of TV).

Summer fog is common along the Maine coast, but Bishop found foggy weather good for working. Her observant eye finds abundant metaphors—“In the short grass a gauze (?) of dew,” for instance—and she began several poems on the island. She also read constantly, scribbling down thoughts on writers old and new. Some judgments are tantalizingly brief; for example, “H.V.’s [Helen Vendler’s] book on [George] Herbert is driving me crazy!!”

Surprisingly, given her praise of island tranquility, Bishop seems to welcome company, cheerily listing fresh-caught lobster and clams or chocolate mousse that she’s fixing for visitors. Boston poets Frank Bidart and Lloyd Schwartz, British artist Kit Barker and his wife Ilsa, Canadian-born poet John Brinnin and his partner Bill Read, and poet Rhoda Sheehan are regular visitors, but only New York City architect Harold Leeds and his partner, documentary filmmaker William Galantine, get singled out as “good guests.”

The journal keeper is not always cheerful, of course. “Bad day / ache all over,” reads one entry. Arthritis was a persistent complaint, along with her lifelong struggles with asthma, alcoholism, and depression. And bad news reached the island quickly. It was there that Bishop first heard of her close friend Robert Lowell’s sudden death. The elegy she wrote for his memorial is titled “North Haven.”

The Journal illuminates a more intimate story still, Bishop’s relationship with the much younger Alice Methfessel, an administrator at Harvard University, where Bishop had begun teaching in 1970. (She was then 59; her partner Lota de Macedo Soares had died three years earlier, an apparent suicide.) The women grew close, but their friendship collapsed when Methfessel became engaged to a man she had recently met. Despair over this impending loss prompted the poet’s remarkable villanelle, “One Art.”

Happily, Methfessel and Bishop reunited, and Journal comments give a sense of their easy, everyday love. Bishop jokes about the term Alice (“A”), coined to describe their messy barn swallows—“shit-bottoms”—and comically recounts the pair’s 3 a.m. departure from Cambridge and drive to Maine at breakneck speed one July to catch an early ferry. The couple’s intimacy is apparent: “14th we went to the ‘3rd beach’ around 5PM—intensely quiet, slightly hazy—lovely. A went in naked—water very clear, lap-lapping.”

During the years that she went to North Haven, Bishop’s reputation as a writer reached new heights. She was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1978, and soon after returning from a trip with Methfessel to London, Greece, and Yugoslavia in early 1979, she accepted a fifth honorary doctorate from Princeton University. But the poet was exhausted. Her health grew worse, and she died of a ruptured cerebral aneurysm at her Lewis Wharf condo in Boston that fall. What endures is Bishop’s extraordinary poetry, as well as the island that sustained her later years.

Rosemary Booth is a writer and photographer living in Cambridge, Mass.