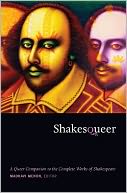

Shakesqueer: A Queer Companion to the Complete Works of Shakespeare (Series Q)

Shakesqueer: A Queer Companion to the Complete Works of Shakespeare (Series Q)

Edited by Madhavi Menon

Duke Univ. Press. 495 pages, $27.95

THIS FASCINATING COLLECtion of essays explores the queer elements within all of Shakespeare’s works. With contributions from scholars of both queer studies and Shakespeare, the volume represents a joining of the two fields rarely attempted before.

Madhavi Menon defines queer theory in her introduction as a “suspicion of institutional constraints” that allows for “varied ideas on queerness, engaging not just sexual identities, but also race, temporality, performance, adaptation, and psychoanalysis.” As a result, this volume discusses all things “odd, eccentric, and unusual” in Shakespeare’s work, not just with respect to sexuality. Even the arrangement of the essays is unconventional, eschewing the traditional chronological order in favor of an alphabetical one. Thus, All Is True, Shakespeare’s co-written play about Henry VIII, begins the volume, while The Winter’s Tale, which happens to be one of Shakespeare’s last works, concludes the collection. Simply placing these classic, familiar plays and poems in this odd arrangement sheds a new light on them, preparing readers for daring, unorthodox, and sometimes amusing discussions of works about which one might wonder if anything new could possibly be said.

Some essays focus more on performances of the plays, such as Hector Kollias’ “Doctorin’ the Bard,” which looks at the lost play Love’s Labor’s Won. Since no text of the play exists, Kollias instead uses an episode of the British science fiction drama Doctor Who, where the main characters encounter Shakespeare as he writes the play, discovering the reason why it vanished (an attempted alien invasion using the play as a summoning device). Although the essay is certainly fanciful and light-hearted, Kollias concludes from this appropriation of Shakespeare’s work that because the inhuman—“always queer”—is always present in telling human stories, GLBT people play a tremendously important role in preserving and passing on the heterosexual majority’s culture, while challenging and disrupting it at the same time. Playful yet serious, the essay reveals the inherent queerness within culture itself, expressed through “the most human human that’s ever been.”

Robert McRuer, in “Fuck the Disabled,” examines the title character of Richard III, mainly looking at Richard Loncraine’s 1995 film version staring Ian McKellen. McRuer begins with the observation that the play’s most famous soliloquy (“Now is the winter of our discontent”) in this adaptation takes place in the men’s room, “the site of a particular heterosexual anxiety about … homosexual desire.” With the film’s emphasis on Richard’s deformities, his hunched back and misshapen arm, the audience begins to connect queerness with disability, since both groups are routinely viewed by the heterosexual, able-bodied world as frightening and potentially evil. Richard becomes genuinely disruptive throughout the work, as he eliminates his rivals and seizes power; he even, according to McRuer, becomes “sexy and queer, in and through the deformity that has made him evil.” Richard III sneers at the world view that links straightness to able bodies, symbolizing the most extreme method of disabled activism; he is “determined to prove a villain.”

In “Othello’s Penis: Or, Islam in the Closet,” Daniel Boyarin finds parallels between the closeted homosexual and the Muslim in the Christian Europe of Shakespeare’s time. According to Boyarin, Othello, born Muslim and raised in that faith, must have been circumcised along with his brethren, an obvious sign of difference when he enters European society. Yet, from the way he acts, he appears no different from any of the Venetians. Indeed, as Boyarin states, “one wonders whether Othello … ever looked at his penis.” In the play, circumcision becomes one of the stand-ins for blackness, marking Othello as alien and “queer” even as he pretends to be just like everyone else. He cannot escape his difference, and eventually must suffer for it.

Steven Bruhm, in “The Unbearable Sex of Henry VIII,” views the infamous king as a forerunner of the modern bear, with his facial hair and wide girth. In fact, Henry reintroduced the beard to England, helping make it a sign of virility and power. Clean-shaven men were now considered effeminate and possibly “sodomitical.” Shakespeare peoples his play about Henry VIII, All Is True, with these bearded, large men, displaying their virility and masculinity before the world. Bruhm argues for Henry’s queerness by pointing out his inability, despite great efforts, to produce a male heir. He also suggests that “growing out” or displaying bear-like attributes might provide an alternative to “growing up” or becoming adult and joining heterosexual society. Henry, with his extreme sexual appetites (as evidenced by his willingness to separate from the Catholic Church simply to marry another woman) and heavy, hairy figure, certainly appears a model for this viewpoint.

In “Milk,” Heather Love argues that Lady Macbeth is “the queerest character” in Macbeth. Not only does she urge her husband to commit horrible acts to seize the throne, questioning his masculinity when he hesitates, she asks the spiritual world to “unsex me here,/ And fill me from the crown to the toe topful/ Of direst cruelty.” She becomes further unsexed when she expresses her willingness to dash out the brains of a child as it sucks from her breast.

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, “Shakespeare’s Ass Play” considers the variations on human–animal relationships from the literal, such as Titania’s lust for Bottom with the head of an ass, to the metaphorical, as in Helena’s desperate plea to her unrequited love Demetrius to “use me but as your spaniel.” Even the changeling boy that Oberon and Titania fight over seems a fetish of sorts; never seen onstage, he is doted on and obsessed over by both fairy rulers, with just a hint that something more than parental love is at work. Although the play presents these unusual interactions in a comic light, bestiality was equated with sodomy in Shakespeare’s time, which adds a darker dimension to such a light work.

Charles Green is a writer based in Annapolis, Maryland.