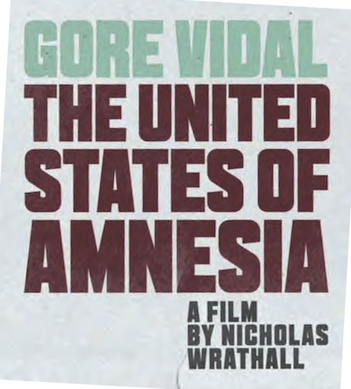

THIS is being written close to a year after the demise of Gore Vidal on July 31, 2012. He outlived Norman Mailer and William F. Buckley, and he outlasted Truman Capote by a long shot. Doubtless this gave him some pleasure in his dotage, which nevertheless had its sad farewells. Some of the latter are observed in Nicholas Wrathall’s new documentary about Vidal’s life and career, Gore Vidal:  The United States of Amnesia, which screened at last June’s Provincetown International Film Festival (among other venues). The director spent many hours with Vidal in various locales (Los Angeles, New York, Cuba, and Ravello, Italy), conducting a series of interviews that form the backbone of the film, which also includes footage from Vidal’s many TV and movie appearances. (Be it noted that near the end of the film a portrait of Vidal is prominently displayed. It was painted by Juan Bastos for this magazine and graced its March-April 2007 cover.)

The United States of Amnesia, which screened at last June’s Provincetown International Film Festival (among other venues). The director spent many hours with Vidal in various locales (Los Angeles, New York, Cuba, and Ravello, Italy), conducting a series of interviews that form the backbone of the film, which also includes footage from Vidal’s many TV and movie appearances. (Be it noted that near the end of the film a portrait of Vidal is prominently displayed. It was painted by Juan Bastos for this magazine and graced its March-April 2007 cover.)

The above-named writers all make an appearance in the film—all three were parties to famous feuds with Vidal—along with countless other well-known writers and celebrities with whom Vidal socialized. Here one has to acknowledge that many of his friendships—with everyone from Tennessee Williams to the Kennedys to Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward—were as enduring as were his rivalries. Vidal reminisces in the film about these lives and times, starting with his childhood as the son of a prominent airline tycoon and public servant and the grandson of a Tennessee senator. We learn about his service in World War II and his torrid friendship with a boy named Jimmie Trimble, who died in the War and became a permanent part of Vidal’s personal mythology.

By that time Vidal had already tried his hand at writing fiction, and by 1948 he was publishing the groundbreaking gay classic The City and The Pillar (about which a separate piece appears on page 22). The book was a breakthrough not only for its depiction of an intimate relationship between two men but also for the fact that Vidal had effectively outed himself at the tender age of 22, a decision that would affect the rest of his literary career. And yet, for all his precocious outness, Vidal was always curiously coy about this very subject, never quite owning up to the label “gay” and eschewing an active role in GLBT politics. He had a lifelong partner, Howard Austen, who died shortly before the film was shot, but claimed they had no sexual relationship after the first night, which is why they lasted so long.

Vidal would go on to write two gonzo bestsellers, Myra Breckinridge and Myron, which dealt with transsexuality in a way that would probably be considered politically incorrect today. But for the most part he stuck to the historical novels (Burr, 1876, Hollywood, Julian, and so on) and never returned to the themes of The City and the Pillar (which he revised many years later). Still, one has to believe that being gay was instrumental in his decision to reject his elite upbringing and become a gadfly to the rich and powerful, an outsider, a “traitor to his class.” Indeed, what may be Vidal’s most important legacy was his exposé of the inner workings of power and wealth, and his relentless critique of their concentration in the U.S.—what he saw as a shadow plutocracy that rendered the political parties and processes largely irrelevant.

Gore Vidal is Nicholas Wrathall’s second documentary, and he has been a producer of several films since 1999. This interview was conducted via e-mail by the GLR editor in late June.

The Gay & Lesbian Review: you spent a lot of time with Vidal during the last few years of his life, and the result is a lot of fas- cinating footage of the wizened but still razor-sharp Vidal speaking into the camera. How much time did you end up spending with Gore Vidal?

Nicholas Wrathall: I saw Gore about a dozen times in the first few years of knowing him, 2005 to 2007. These included ex- tended trips to Venice, Havana, Washington, DC, and New york City. I also visited him at his houses several times in this pe- riod, both in Ravello and in Hollywood Hills. In 2008 I saw him a couple more times, including interviewing him on election night. After that I saw him less frequently as I was not in Los Angeles much in 2009. I then reconnected with him in 2010 a couple of times including interviewing him at his Hollywood home for the final time. I also visited him in 2011 but he was quite sick by then.

GLR: You seem to have caught him at certain key moments, notably when he was packing up and leaving Ravello after three decades of living there six months of every year. How did that come about? What was it like?

NW: Yes, it was an amazing opportunity to go to Ravello and visit him. I had only met him once or twice at that point [2005]. His nephew Burr Steers informed me that he was packing up the house and leaving Ravello, and so I immediately headed out there to film him. He was very reflective and rather sad when I saw him in Ravello. It was an emotional time for him as he was leaving the villa for the last time. He spent a lot of time sitting at his desk and looking out to sea and reflecting on his life there. Howard had passed away two years earlier and I think Gore felt very alone in the house but torn about leaving.

GLR: you tell the story through an interweaving of recent in- terviews and flashbacks that extend from Gore’s childhood to his late career. There’s a chronological flavor but nothing heavyhanded. How did you decide to organize the film in this way?

NW: I wanted the film to follow both Gore’s life and his criti- cism of the U.S. empire as he saw it. It was difficult to find a structure to balance both goals while also following Gore’s last few years. We spent a lot of time editing and trying different structures before we found this balance. We also had to bring in the emotional content of his life with Howard. By focusing on Gore and minimizing other people’s analysis of him, basically letting him speak for himself, we were able to use my inter- views together with the archival footage to tell the story. Seeing Gore at different periods in his life throughout the film, I be- lieve, is a great strength and, although slightly unconventional, enabled us to see his story and hear him commenting on it at the same time.

GLR: I’d forgotten how central his mother was—and not in a good way. This hostile and distant relationship runs counter to the “mama’s boy” stereotype. Indeed Vidal seems to have been more bonded with the men of the family, including his father and especially his grandfather. Any significance in the devel- opment of his sexual identity and approach to relationships?

NW: I think his difficult relationship with his mother was a key character-forming element for him as a child and probably is re- flected in the emotional distance he kept in his close personal relationships.

GLR: You do focus a fair amount on The City and the pillar, a novel that’s discussed fondly by a writer in this issue of the GLr [below], who says the book gave him a model for being gay in the 1950s. It was a huge risk for Vidal to write this book so early in his career. What was he thinking?

NW: It was a big risk, and one that I think he considered very deeply. His publishers advised him against putting out The City and the pillar. It damaged his political ambitions and his stature as a serious novelist. I think he realized the importance of the book, and in a way he wanted the notoriety. He liked the idea of shaking up the discourse at the time. It did take courage, and I think one of Gore’s strongest and most inspiring traits through- out his life was that he was unafraid to speak his mind. He was able to speak truth to power on this and many subjects through- out his life.

GLR: He always spoke as if he had looked into the heart of power—he alone!—and it’s not a pretty picture. The “conspir- acy” is real—they only want you to think that you’re crazy. But he’s sometimes vague on this point. What is the nature of this conspiracy as he saw it?

NW: I don’t think he would characterize it as a conspiracy but more as class-based control. That those of the upper and ruling classes were mostly very alike in their views and in wanting to increase and retain their power and dominance in society. That they, as he said, “all thought alike” and so would protect their interests at any cost. Growing up with his grandfather, Senator Gore, I think he saw firsthand the way Congress worked—the deal-making and so on—and never trusted the people in power to look after the interests of the people.

GLR: Vidal was almost as cynical about romantic love as he was about politics—except when it came to his brief affair with Jimmie Trimble, who died in the War and seems to have taken on some sort of mythical significance for Vidal. What’s your analysis?

NW: I agree that he mythologized Jimmie Trimble and their childhood relationship. I think the fact that Jimmie died so young enabled Gore to put him on a pedestal. It also galvanized Gore against war. He saw firsthand the loss of Jimmy and all those young men of his generation in World War II as an enor- mous and unnecessary tragedy.

GLR: Then there’s Howard Austen, Vidal’s lifelong “partner” with whom he allegedly never had sex. Austen died before you began making the film, so he remains a background figure. What do we know about him other than that he was Vidal’s con- sort? What role did he play in Vidal’s life?

NW: Howard and Gore were best friends and probably more when they were young men and first together. They were longtime companions and despite their non-sexual relationship re- mained very close, living together for many decades. Howard also managed their affairs and social life and was a sounding board for Gore. I think Gore really fell apart after Howard died, and it was only after he left Ravello behind in 2005 that he was able to pull himself together.

GLR: Vidal is one of those people—like, say, Leonard Bern- stein—who did so many things so well that it’s hard to know what he’ll be remembered for. The historical novels, the gonzo novels, the essays, the interviews, the plays and screenplays. Or will he be remembered as a kind of legendary figure like Lord Byron or Oscar Wilde, “more myth than man,” as he liked to say?

NW: I hope he lives on as a larger than life character for both his work and his outspoken criticism of American politics and society. I hope he inspires us all to look beyond the media prop- aganda and really question the motives of those in power. Amer- ica really needs the likes of Gore Vidal to keep questioning media representation, especially now. Who can possibly step into his shoes? He knew so many people from the second half of the 20th century. I think his is a hard act to follow. I hope this film reaches many people and that they realize the importance of Gore Vidal as both a writer and a critic and celebrate the mag- nificent life that he lived.