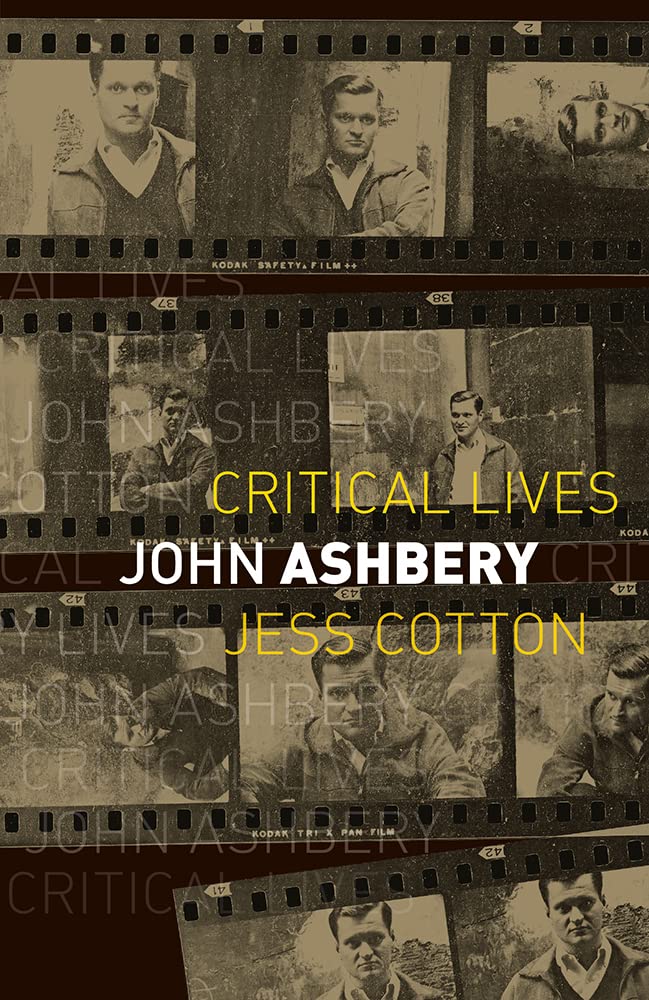

JOHN ASHBERY (Critical Lives)

JOHN ASHBERY (Critical Lives)

by Jess Cotton

Reaktion Books. 210 pages, $22.

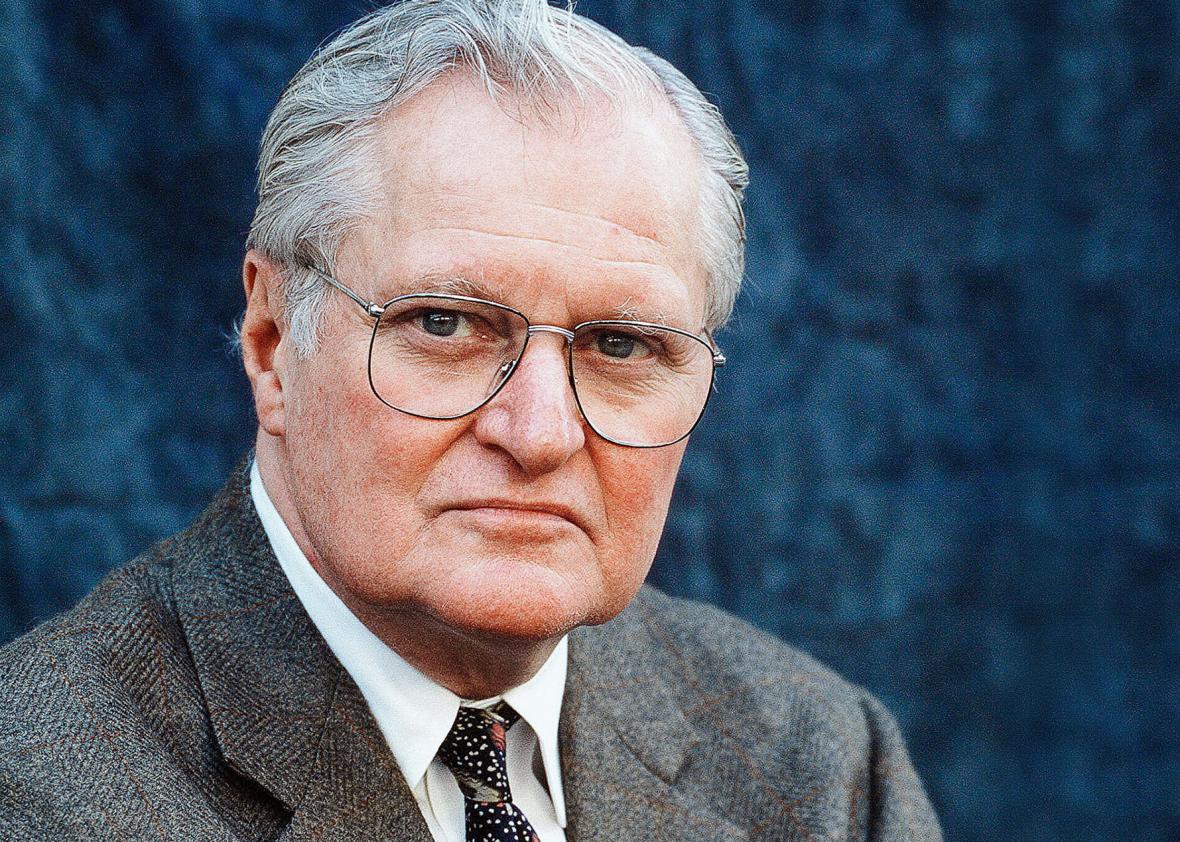

POET JOHN ASHBERY (1927-2017) is described by Jess Cotton in Critical Lives as “at once notorious and celebrated” owing to the perceived difficulty of his work. Cotton’s short but thorough explication of Ashbery’s life and work does a fine job of placing him both as a 20th-century poet and as a leading figure among gay writers. The book is part of a series published in Great Britain that includes scores of biographies focused on the writer’s work, including well-known gay writers such as Jean Genet, Allen Ginsberg, Yukio Mishima, Marcel Proust, Susan Sontag, and Tennessee Williams.

Cotton explains that Ashbery was semi-out at Harvard and became more relaxed about his sexuality during time spent in France in the late 1950s. During this period, his writing style began to take the “hunter-gatherer” shape that it would later retain, featuring all manner of bits and images of life that made up what he saw as an authentic representation of culture and daily life. He rarely met an object, name, or idea that he couldn’t fit into a poem. Unlike Hart Crane, whose style sometimes looks similar but whose ornate waterfalls are mostly fancy words, Ashbery’s glitter tends to be from physical objects and, unlike Merrill’s, feels more discovered than constructed. The result became an œuvre of shimmering images rushing at, into, and past the reader. He was not the only poetic collector in his era, as Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, and Gregory Corso were exploring a kind of found poetics, and Robert Duncan’s partner Jess was a collagist in the traditional sense. But Ashbery became the beacon for this approach.

Still, Ashbery wasn’t just a poetic bowerbird gathering colorful objects for display. No one could say that a line like “I’ll brush your bangs/ a little, you’ll lean against my hip for comfort” lacks lyrical beauty or is in any way obscure. He was a prolific writer on art as well as poetry. Sometimes his other writings attracted comparative attention, as when Mary McCarthy grumbled that she wished his poetry were as clear as his prose.

Unlike poets who require uninterrupted alone time, Ashbery was a profoundly social creature, enjoying people and building various interruptions into the flow of his poems. His poetry is nonlinear to begin with, often a series of observations, switchbacks, and outbursts, much like life itself, which he celebrated.

By the 1970s, Ashbery was comfortable riding the wave of gay visibility, living with his long-time partner David Kermani, and talking openly, albeit playfully, about Gay Pride. Like Merrill, Ashbery was not a noisy presence in the gay rights movement of the 1970s and ’80s. He tended to his private poetic gardens, gave Harvard lectures on poetic subjects, and focused on his many friendships and on-again, off-again writing projects. In his longest poem, “Flow Chart,” written during the AIDS crisis and published in 1991, he assigns himself the role of one invisible gay person among many:

It occurs to me in my home on the beach

sometimes that others must have experiences identical to mine

nd are also unable to speak of them, that if we cared

enough to go into each other’s psyche and explore

around, some of the canned white entrepreneurial brain food

could be reproduced in time to save the legions

of the dispossessed, and elephants.

Cotton quotes these lines but for some reason ends with the incorrect word “disposed” and omits the final two words, “and elephants.”

Not long after this, Ashbery’s work became the subject of a book by John Shoptaw, On the Outside Looking Out (1995), which discussed the “homotextual” content of his work, an approach that Ashbery considered unduly reductive. He grumbled about being treated as a gay symbol, e.g., for New York City’s John Ashbery Day and for LGBT History Month in 2011. Cotton notes that he objected to “the notion that gay writers are sort of expected to talk about sex or their sex lives in public.” Ashbery was too private a person for that, and he rarely alluded to gayness as such in his poetry. He once told an interviewer that “I don’t write about my life the way the confessional poets do.”

The late gay poet J. D. McClatchy once wrote that in the arts “the 20th century’s characteristic innovations [are]collage and abstraction.” If that is true, surely Ashbery’s place as one of the main anchors of this movement is secure. That he was a well-known gay icon, whether or not he enjoyed being one, is a source of pride in the larger community of gay people of which he clearly enjoyed being a part.

Alan Contreras is a writer and higher education consultant who lives in Eugene, Oregon.