WE MAY HAVE canonized Oscar Wilde for his proto-gay life and martyrdom in late 19th-century England, but we tend to treat the very end of his life with either morbid fascination or awkward avoidance. Wilde’s premature death after serving his two-year jail sentence is somehow our own: an individual and collective gay failure. Our god died in his third year after prison instead of rising on the third day. It causes us to doubt our faith, if not in Wilde’s iconoclastic gospel, then in the hagiography of the modern LGBT movement. We don’t want Wilde to be a camp, tragic figure whose crucifixion and death are bathos, but rather a charismatic savior who died for our equality movement.

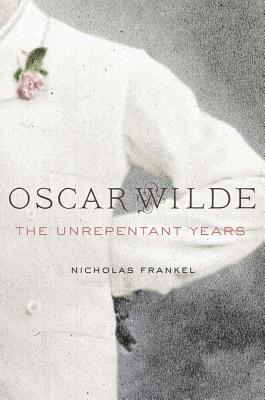

In Oscar Wilde: The Unrepentant Years, Nicholas Frankel proposes that we consider Wilde’s final years outside of time, apart from what came before and what will follow. He also hopes that we will look at Wilde honestly in all his failings, and that we’ll respect his personal agency during that period rather than assume he was a broken man or Bosie’s plaything. Frankel’s Wilde is human, real, and didactic. The focus on Wilde the prisoner and lover humanizes him. Bosie Douglas, typically portrayed as Wilde’s Judas, comes closer to a beloved disciple in this version.

Frankel describes Wilde’s later life as “entirely unapologetic and uncompromising.” He claims that the narcissistic and aristocratic Bosie showed neither “lack of love” nor “failure of sympathy.” He asserts that Wilde continued a prolific, more authentic artistic life after prison. He argues for the formal merit of The Ballad of Reading Gaol, notes that Wilde revised plays for publication, and shows that he lived a more openly gay life while in exile. He details the material conditions of prison life as well as his subject’s reading and writing resources. He gauges Wilde’s moods with respect to Douglas in his famous prison letter “De Profundis.” Frankel counteracts doubts about their mutual love and expectation for reunion.

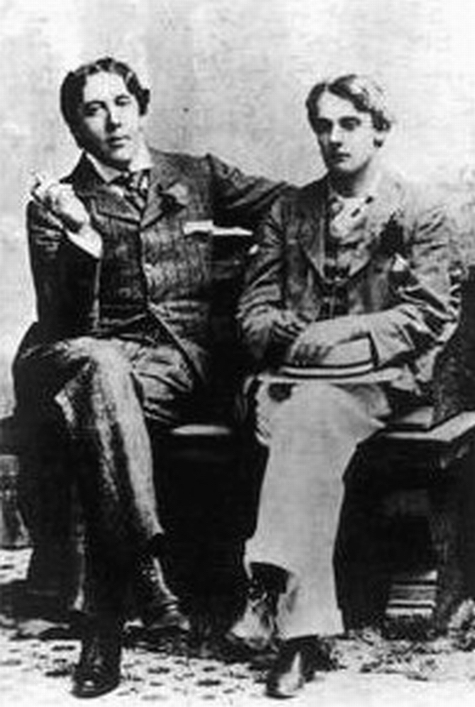

Wilde lived and loved with Bosie in Naples. Evidence suggests that their sexual relationship had ended years earlier, but Frankel describes something more poignant: they become a gay couple. We usually dismiss Bosie as a selfish opportunist; David Hare’s excellent 1998 play The Judas Kissleaves us with this viewpoint. Through a sensitive reading of both of their writings, Frankel describes two men in love, struggling with circumstances that pulled them apart. He posits their cohabitation as a radical gesture.

After going broke and losing Douglas, “Wilde’s very existence was a calamity.” Even so, Frankel reclaims The Ballad of Reading Gaolas a “moving and unapologetic reassertion of Wilde’s sexual orientation.” The remaining 33 months of his life, spent in Paris, “offered a greater sense of personal and sexual freedom.” This was Wilde’s most “out” period as a gay man, though he continued to suffer great feelings of loss over his wife’s death and his permanent separation from his sons.

Frankel faces the realities of Wilde’s decline: his lies and irresponsibility over money, excessive drinking and whoring, and physical weakness. Frankel does not whitewash. His portrait provokes more compassion for the broken human than any other that I’ve read. Hope and despair, being seen and not seen, are developed through Wilde’s late fascination with a camera, which he used to capture the world and glimpse himself. His final days were a new via dolorosa.

The tendency to deify Wilde is palpable in Frankel’s extraordinary book. Moving away from his fall from grace, Frankel refuses to see him as a “martyr to Victorian morality” or as “Alfred Douglas’ victim. To view Wilde this way is to rob him of all agency.” While some readers will resist the essentialism inherent in Frankel’s view of Wilde as a proto-modern gay man, the author has made a convincing case for extending the heroic image into his final years.

Frederick S. Roden teaches literature at the University of Connecticut. He edited a guide to Wilde studies for Palgrave Macmillan.