Good Night, Beloved Comrade: The Letters of Denton Welch to Eric Oliver

Good Night, Beloved Comrade: The Letters of Denton Welch to Eric Oliver

Edited by Daniel J. Murtaugh

Wisconsin. 232 pages, $29.95

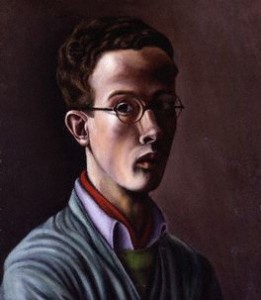

DENTON WELCH (1915–1948) was a writer’s writer and, in particular, a gay writer’s writer. He isn’t as well known as other queer authors of the early 20th century, but the list of writers who have admired and championed his work includes Edith Sitwell, Vita Sackville-West, E. M. Forster, W. H. Auden, John Updike, William Burroughs, John Waters, and Edmund White.

Welch died young, at 33, succumbing to injuries he sustained at age twenty when he was run over by a car while bicycling in the English countryside. Although he aspired to be a painter, and had some success at it, it’s fair to say that he found his true calling as a writer, which might not have happened if he hadn’t been forced by his accident into a long convalescence. He’s known mostly for three autobiographical novels, Maiden Voyage (1943), In Youth Is Pleasure (1945), and A Voice Through A Cloud (1950), unfinished at his death but published posthumously. (All the novels remain in print, from Exact Change, an independent publisher.) He also published a collection of short stories, Brave and Cruel (1948), wrote many other stories and poems, and left behind extensive journals, which were published in 1984. Welch accomplished all of this in a roughly ten-year period during which he endured many painful medical setbacks, even as German bombs rained down on England. One can only wonder what he might have accomplished had he lived longer.

Beloved Comrade marks the first complete publication of Welch’s love letters to longtime companion Eric Oliver. He met Oliver by chance, and there was an immediate connection. Though their relationship was emotionally stormy (as shown in the letters), Oliver proved to be a devoted friend. He outlived Welch by nearly fifty years and is largely responsible for solidifying his literary reputation. Among other things, he ensured that Welch’s last novel was published. Unfortunately, Oliver destroyed all but one of his own letters to Welch, so Beloved Comrade is a somewhat incomplete view of their relationship.

In Welch’s highly autobiographical novels, his relatives and friends are barely disguised, and the circumstances of his unusual upbringing and schooling are revealed through his first-person narration. Indeed, his fiction could almost be described as memoir. He refers to himself by name in his first book, Maiden Voyage, an act of considerable courage given the book’s homosexual content. W. H. Auden praised the debut novel in a review for The New York Times. Welch quickly drew the attention of gay readers and received his fair share of fan mail, some of which led to visits and friendships. (He had actually blipped the radar a year earlier with his first published work, a bitingly funny article for Horizon about his strange meeting with the painter Walter Sickert.)

By today’s standards, the sex depicted in Maiden Voyage is tame. The actual sex is suggested rather than described in detail, but readers clearly knew what was going on. Welch spent a lot of time cruising for and flirting with military men and laborers, and these efforts are described in detail in the novels and the journal. He seemed to abhor many of the gay men he met, and he particularly disliked academic types, preferring rough trade. He had a wonderful eye for detail, and the novels often read like collages of scenes and vignettes, many erotic and startling. For example, there’s this scene from Maiden Voyage, which takes place during a visit to the Chinese interior:

I looked into the dark mouth of a doorway and saw a bare chest and arm moving backwards and forwards rhythmically. The man stopped his pumping and came and stood in the doorway. He saw me staring and lifted his head, so that the sun fell on his magnificent chest and arms, making them glisten. He was like no other Chinaman I had seen. He had not the immature, slight look. He was more like a Roman boxer or athlete, glistening with oil. … I went into the garden and leant against the doorpost of the hut. He did not stop pumping. … I touched the muscles as they raced across his back under the elastic skin. He did not even look up.

The passage is remarkable not only for its sexual content but also because the object of his admiration is Chinese. There’s a fair amount of condescension in Welch’s general descriptions of the Chinese (particularly his renderings of the pidgin English used by Chinese servants and their masters), but he was ahead of his time, here and elsewhere, with respect to his sexual confessions.

Welch also revels in descriptions of architecture and antiques, both special passions of his. Indeed, he focuses so much on the houses and possessions of family and acquaintances, betraying a preoccupation with objects over people, that one wonders if he might have had a spectrum disorder such as Asperger’s syndrome. Still, he’s an acute, acerbic, and often hilarious observer of human nature. His novels and journals provide a wealth of detail about life as a gay man in wartime Britain, and the richness and offbeat nature of his narratives make for memorable reading. In Youth is Pleasure, his follow-up to Maiden Voyage, continues the story of Welch’s peripatetic education and his intense interior life. His last novel, A Voice Through a Cloud, is an extended meditation on his accident and the suffering it caused. Many critics consider it his finest book.

The portrait of Welch that emerges from his fiction is of an isolated youth who prefers solitary walks and secret explorations. He is fascinated by antiques—he collects old spoons and parts of tea sets—and yearns for the past in a way that seems related to his idealized memories of his dead mother. Though self-conscious and easily intimidated by boys his age, he is also rebellious, quick on his feet, and unafraid of adventure. The letters to Oliver, nicely edited by Daniel J. Murtaugh, provide an even fuller portrait of the writer and his one true love.

Though intellectually Welch’s inferior, Oliver was intelligent, with dark good looks and a muscular frame. Welch remained enchanted with Oliver, yearning for sexual and emotional intimacy with him even as Oliver pulled away. Despite an initial spark, the sexual attraction eventually faded for Oliver, a development exacerbated by his bisexuality and hesitancy to commit to any one lover. Their correspondence was relatively brief—51 letters over a roughly four-year period. Murtaugh supplements these with a ninety-page section of notes that draws upon Welch’s fiction, journals, other correspondence, as well as biographies by Michael De-la-Noy (1984) and James Methuen-Campbell (2002). General readers may want to read the novels before delving into the letters, but Murtaugh’s detailed notes provide excellent background for those encountering Welch here for the first time.

Jim Nawrocki, a writer based in San Francisco, is a frequent contributor to this magazine.