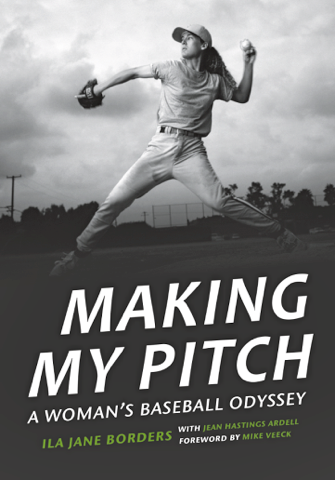

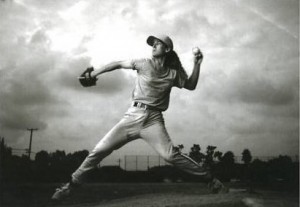

ONE MORNING in 1994 I picked up the Newport Beach-Costa Mesa (Calif.) Daily Pilot and read that a young woman named Ila Jane Borders was pitching that afternoon for the men’s team at nearby Southern California College. That beat sitting behind a cluttered desk, and I drove over to the watch  the game. The mood was electric, the stands crowded with students in “Jammin’ for Jesus” caps and “In the Beginning, God…” T-shirts—SCC is affiliated with the conservative Assemblies of God denomination—and the media was all over this story. Borders was in the zone that day, and stepped into history as the first woman to pitch a complete game in men’s collegiate baseball, ending with a twelve-to-one victory.

the game. The mood was electric, the stands crowded with students in “Jammin’ for Jesus” caps and “In the Beginning, God…” T-shirts—SCC is affiliated with the conservative Assemblies of God denomination—and the media was all over this story. Borders was in the zone that day, and stepped into history as the first woman to pitch a complete game in men’s collegiate baseball, ending with a twelve-to-one victory.

Two thoughts struck me that day. First, as I stepped across the foul line to join the other reporters for the post-game interview behind second base, I felt an invisible resistance, as if my presence wasn’t welcome on the field. This felt weird as I’d grown up playing baseball—very unorganized and unsupervised, in Jackson Heights, N.Y.—where I felt very much at home on the field. But this was an official men’s field, home of the SCC Vanguards, and, as I would soon learn, not all of Borders’ teammates were happy to share that field with her. I wondered how she felt each time she jogged to the pitcher’s mound: did she feel the same resistance? Second, I knew that I wanted to follow her story for as far as it went. She intrigued me, this pony-tailed born-again Christian pitcher who said she loved God and baseball, though she sometimes mixed up the order of those priorities.

As I got to know Ila through her four seasons of pitching varsity baseball and four more seasons of men’s professional baseball, I felt more than ever that hers was a story worth telling. Her opponents’ horror at striking out against a female pitcher was just as strong in the pros as it had been in Little League. The scrutiny by the press was relentless—“Why not play softball?” “Do you consider yourself a feminist?” “Are you gay or straight?” Ila was grudging in her responses to these questions. To survive, she retreated within herself.

I happened to be visiting Ila while she was pitching for the Duluth-Superior Dukes of the independent Northern League, when she was suddenly traded to the Madison Black Wolf. I offered to drive her to her new team, and during the long night’s drive to Wisconsin we talked about her life in baseball. “Your story deserves a book,” I said, “When you’re ready, let me know.”

It would take a decade until she was ready. The manuscript was generated mostly via e-mail, with Ila downloading her journal entries while I organized them and filled in the background. We proceeded nicely until we got to Chapter 8, in which Ila wrote of falling deeply in love. She called him “Shane.” Before I could edit the chapter, she sent a distraught email. “I’ve got something to tell you, and I’m afraid it’s going to ruin the book.”

What Ila had to tell me was that she was gay (her preferred term), and “Shane” was actually a woman named Shannon. I got her on the phone and explained that telling the truth was not going to ruin the book. If anything, it improved it, the path to hell being lined with memoir writers who had made stuff up. Besides, times and attitudes were changing—it was 2014—and I believed she could still be the role model she aspired to be for girls who dreamed of playing baseball. After all, she was a born-again athlete with the courage tell the truth about her life. But it’s one thing to edge out of the closet to family and a few friends; it’s another thing to come out in print for the whole world to read. It had to be her call.

Ila decided to take the risk. She also came out at her workplace, which was the Gilbert, Arizona, Fire Department, where she had worked as a firefighter and paramedic since her baseball career ended. The news made barely a ripple. A year later, one of her captains thanked her, saying his teenage daughter had recently told him she was a lesbian and that he wouldn’t have known how to handle it if he hadn’t heard Ila’s story.

Since the publication of Making My Pitch: A Woman’s Baseball Odyssey last April both Ila and I have heard from evangelical Christians who wanted to thank her for telling the full truth. They say the book has helped them to better understand what it’s like to be gay. These contacts can also stimulate conversations that Ila and I are happy to engage in. One point we make is that it’s possible to be both a Christian and a wholehearted supporter of same-sex love and marriage.

In the months since the presidential election, I have felt guilty for not continuing with the political columns I used to write. Given the dissent roiling our nation, why write about our National Pastime? The institution of baseball has always served as a lens through which to examine many aspects of American culture, from U.S. foreign policy and immigration to business practices and racial issues. So I find some comfort in a comment attributed to the formidable activist and author Grace Paley: “When you write, you illuminate what’s hidden, and that’s a political act.”

While I find it unsettling that in 2017 it remains a political act to share the truth about one’s sexual orientation, without shame, to either loved ones or total strangers. But it is and always has been the writer’s job of a writer to illuminate what is hidden. For doing just that in her memoir, Ila Jane Borders is to be applauded.

Jean Hastings Ardell lives and writes in Laguna Beach, California.