Michael Denneny (1943-2023), co-founder and co-editor of the pioneering gay magazine Christopher Street (1976-1995), gay newspaper New York Native (1980-1997), and gay publishing line at St. Martin’s Press, Stonewall Inn Editions, begins his recently published collection of essays On Christopher Street (2023) with a quotation from his mentor, Hannah Arendt (1906-1975), a German-American historian and philosopher:

Only in our speaking with one another does the world, as that about which we speak, emerge in its objectivity and visibility from all sides. Living in a real world and speaking with one another about it are basically one and the same.

Denneny’s career as a gay cultural activist could be viewed as a way of putting into practice Arendt’s thought as condensed in this citation. Across the writings collected in On Christopher Street, which range in date from the beginnings of the magazine to just before Denneny’s death, he consistently grounded his view of gay politics in Arendt’s work. He deserves to be better appreciated as a key figure of modern American gay life for his editorial work, and as one of its most important thinkers.

Denneny met Arendt while an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, where she taught from 1963 to 1967. He started a PhD under her supervision, continuing it until 1971, when he followed her to New York and began a career in publishing. His nearly-finished dissertation explored the concept of ‘taste’ in early modern Europe, a subject apparently unrelated to politics, let alone gay culture. But this historical-philosophical investigation was close to Arendt’s own concerns in the last years of her life, as she developed the idea that aesthetic judgment was of vital political relevance.

A few months later, after he abandoned his dissertation and began looking for work in publishing, Denneny wrote to Arendt again, quoting from his earlier letter: “I shall get a dose of my own thesis and learn to orient myself in the world without fixed points of support.” The description, of course, fits his own personal position of being nearly thirty and jobless in a new city, and the general predicament of our modern era as he had described it, with its characteristic decline of traditional values. But it applied as well to the characteristic problem of gay men discovering themselves as they built a community in post-Stonewall New York. At all three levels of analysis—individual, universal, and between them, the communitarian—taste named for Denneny the means to orient oneself, through the use of pleasure, in the world, and to remake it.

After Arendt’s death four years later, Denneny arranged for the publishing house that by then had hired him, St. Martin’s Press, to publish The Recovery of the Public World, a volume of essays by scholars dedicated to what he took to be the major theme of his mentor’s work. He emphasized the role of taste, or what Arendt more often called “judgment,” the exchange of ideas about aesthetic, ethical, and political values, in making a “world,” a community grounded in both objective reality and our debates about our different perspectives on it.

Denneny’s contribution, “The Privilege of Ourselves: Hannah Arendt on Judgment,” his only academic publication, is frequently cited by scholars of Arendt for the invaluable light it throws on her late work. But it deserves to be read as well in light of Denneny’s dissertation, and his decision in the mid-’70s to ‘out’ himself as a gay publisher. Indeed, the essay and dissertation together can be interpreted as a way of theorizing the purpose and stakes of the new form of gay cultural politics Denneny was helping to shape.

While there were a handful of openly gay publishers (such as Felice Picano and Winston Leyland) at small independent presses throughout the country, there wasn’t anything like a publicly gay man at one of the major publishing houses developing a line of fiction and non-fiction written by gay men for gay audiences before Denneny. Outing himself and creating the Stonewall Inn Editions line at St. Martin’s opened new doors for dozens of gay writers over the following two decades.

Even more momentous was Denneny’s participation in the founding of Christopher Street in 1976. Along with collaborators like Charles Ortleb and Edmund White, Denneny created a space where gay men could speak to each other about concerns from literature to politics to sexuality. Its role in promoting writers like Andrew Holleran and George Stambolian, whose work laid the foundation for ‘gay literature’ in the modern sense, can hardly be overstated—nor can its role in solidifying the aesthetic and habitus of urban gay men of that era.

Denneny’s two roles, at St. Martin’s and Christopher Street, blended together, with the magazine often serving as a venue to try out short stories and essays that, if successful, could be turned into full-length books for Stonewall Inn Editions. Perhaps the most original, and enduringly significant, of the publications Denneny promoted were experimental forms of reporting that showed the diversity of gay life, and demonstrated that apparently intimate problems were part of a gay world.

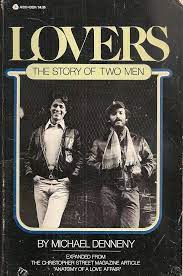

He published in 1979, for example, first as a feature story of the magazine and then in extended version as a book, Lovers: The Story of Two Men, an innovative double interview with two men who had been a couple for years and recently broken up. Denneny argued in his preface that it was of vital importance to “make such utterly private matters public,” not because the two men had been a “representative” gay couple (there was no such thing) but because in their “urgent need to understand what happened and why,” they shared the situation of gay men in the “uncharted territory” of post-Stonewall life.

Just as modern society generally, as his teacher Arendt had argued, had seen the collapse of traditional norms and could only be navigated by the mutual exercise of judgment, by which people expressed to each other their private thoughts and desires to arrive at a common understanding, so too could the particular domain of the new gay culture only by navigated by seeing how our apparently private relationships and quests for self-understanding connected us to a community.

Understood in this context, the title of Denneny’s volume in tribute to Arendt—The Recovery of the Public World—is revelatory. A “public world,” the possibility of speaking to a multitude of other people about what each of us perceives, understands and takes to matter—about topics of taste or judgment in the most extended sense—was invaluable and second endangered. As Denneny elaborated in his essay, “The Privilege of Ourselves,” this was a warning that resounded throughout Arendt’s work, in response to the catastrophes of the early and mid-twentieth century.

In her classic work The Human Condition (1958), completed shortly before Denneny began studying with her, Arendt outlined a grim vision of modern life in which politics—the possibility of people self-consciously undertaking activities in common that matter, and creating something new in the process—was disappearing. Three years later, in an essay, “The Crisis in Culture,” which Denneny argued was the heart of her later work, she suggested that the best hope for the revival of politics lay in cultural action by minorities willing to risk the public expression of their “taste.”

It is easy to see why “The Crisis in Culture” would have special appeal to Denneny. Arendt called in it for members of a minority defined by their particular way of appreciating beauty to recognize each other not only as bearing common traits or sharing the same interests, but as constituting, in their minoritarian pleasures and, critically, in their discourse about them, a “world” in which interlocutors have different perspectives on common objects—and as they came to share an awareness of this world to rediscover “politics” in her special sense: the power to invent new forms of freedom together.

Blake Smith, a historian and literary translator, is an international research fellow at the Centre for Advanced Study in Sofia, Bulgaria.

Blake Smith, a historian and literary translator, is an international research fellow at the Centre for Advanced Study in Sofia, Bulgaria.