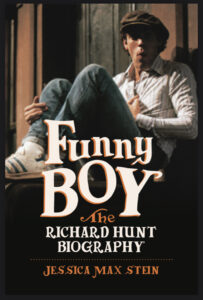

My book Funny Boy, the biography of gay Muppet performer Richard Hunt, began as a labor of love – as well it should have.

When I was a kid in the ’80s, in America’s rust belt suburbia, the Muppets were everywhere: television, movies, books, records, toys. They were part of the very fabric of my life (I even slept on Kermit-print sheets.).

I rediscovered the Muppets about twenty years later when I was living in Brooklyn, trying to find my footing as an independent adult. Once or twice a week, my next door neighbor Effie and I would eat dinner together, watch The Muppet Show and laugh our heads off. In a frightening, unpredictable world, the Muppets were one of life’s reliable joys. I adored the dynamic of “affectionate anarchy” (Frank Oz’s phrase) among the characters; they treated each other with genuine kindness, even as they blew each other up.

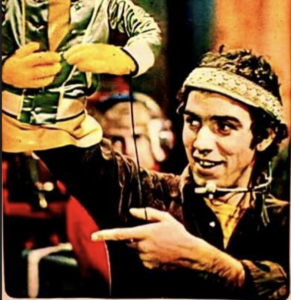

But now, I noticed the vast amounts of effort and illusion that brought these puppets so vividly to life. One performer (Richard Hunt) in particular grabbed my attention. He played most of my favorite characters, a broad range of personalities from young, eager Scooter to old, jaded Statler; groovy, laid-back Janice to squeaking, freaked-out Beaker; huge, gruff Sweetums to an early version of queenly Miss Piggy, and so many more. Yet, various as they were, his characters all carried a certain sensibility, his own individual stamp.

When I found out that Hunt was only forty when

But it was true. Hunt died at forty during the AIDS epidemic,

I caught a glimpse of Hunt in Charles Kaiser’s dishy history, The Gay Metropolis: “What I remember is Richard calling me in the wee hours of the morning — inviting himself down with a quart of orange juice and… pot,” … — recalling his on-again-off-again lover Charles Gibson, a Sesame Street production assistant. “We’d get high and we’d drink our orange juice. And we’d go to bed.”

I sure hadn’t seen that side of him on Sesame Street. Or had I? I loved the detail of the orange juice, like a kid on a happy, sugary buzz. Who was this playful, exuberant character? Now I couldn’t see The Muppets without wondering what I wasn’t seeing. How were Hunt’s characters so iconic, yet he was so invisible? Who was this guy?

I guess you could say I was on a “Hunt”.

I was fascinated by the way Hunt’s life brought together two worlds which are seen as separate, and, in fact, deliberately kept apart. Puppetry is pigeonholed as being only for children–a disservice to a brilliant, all-ages art form — whereas queer topics are thought of as more ‘adult.’ Hunt’s life exploded these boundaries. I was shocked to realize that the peak era of The Muppets was also the peak era of the AIDS epidemic, though these two are rarely thought of together. My Generation-X heart was hooked.

As I uncovered Hunt’s story, I was touched by how he came to terms with his sexuality over the course of his life. Hunt’s experience reflects similar journeys taken by other members of his generation, as one’s life often reflects one’s times. Hunt graduated high school in 1969, the same year as the Stonewall Riots, considered the beginning of America’s LGBTQ+ rights movement. At first he didn’t identify with the gay community, which was just beginning to make sense. He and his lover, Duncan Kenworthy, quarreled over being out with Hunt wanting to hide their relationship. But even as he became more open, he didn’t like the terms gay or queer. When he talked about his sexuality, he’d call himself a “funny boy.” He didn’t let his sexuality define him, and he didn’t let other people define it for him. Characteristically, he defined it for himself–as a joke.

Given Hunt’s outsized, fearless personality, it seems fitting that writing his biography often shoved me out of my comfort zone. I spoke with nearly one hundred of Hunt’s family members, lovers, colleagues, friends and classmates, each of them giving me a little piece of his larger story as I wrote Funny Boy. I traveled to nearly all of Hunt’s beloved places, interviewing people all around Manhattan, New Jersey, Martha’s Vineyard, Truro and Toronto, even taking my first trip overseas to London to research the book. I fought over a lot of restaurant checks, a hallmark of Hunt’s. Mark Hamill’s dog Mabel fell asleep on my lap. I made Frank Oz laugh.

And as I worked on this book, I found Hunt’s personality rubbing off on me. Instead of being wary of people, I was curious to get to know them. Instead of hiding at home with a book (or an episode of The Muppet Show), this hermit started going out. Lo and behold, I fell in love with a woman who lived in New Jersey, just six miles over from Hunt’s New Jersey hometown of Closter. Later, we married.

Jessica Max Stein has been a New York-based queer writer since the early 90s. Her writing has received awards from Poets and Writers Magazine, the Independent Press Association, and the Biographers International Organization, as well as being published widely. She teaches writing and literature at Hunter College of the City University of New York (CUNY). You can pre-order Funny Boy here.

Jessica Max Stein has been a New York-based queer writer since the early 90s. Her writing has received awards from Poets and Writers Magazine, the Independent Press Association, and the Biographers International Organization, as well as being published widely. She teaches writing and literature at Hunter College of the City University of New York (CUNY). You can pre-order Funny Boy here.