In 2015, three months after coming out to myself and three months before coming out to my parents, I sent a fifteen-paragraph email to my therapist debating the merits of cutting my hair.

In the email, I listed all the reasons not to: What if I look ugly? What if I can’t get a job? What if people beat me up on the street for looking gay? Again, what if I look ugly?

Towards the end of the email, I finally said what I really meant: I’m afraid of looking like a butch lesbian.

Later, on a follow-up phone call, my therapist asked me, “Are you scared you won’t like having short hair?”

“No,” I told him. “I’m scared I’ll like it.”

Even then, I could see where this path was leading me—I would cut my hair and like it. Then I would buy men’s clothes and like that, too. I would stop plucking my eyebrows and putting on makeup and the next thing I knew, I would be stuck living the rest of my life as a butch lesbian.

What kind of future could I possibly have then?

Growing up, I certainly knew that butch lesbians existed. But it never crossed my mind that being butch was an actual, viable option for my future. You don’t grow up dreaming of becoming the boogeyman. Dominant, Western culture sees butch lesbians as aggressive, predatory, and ugly. They hit on straight women aggressively. No one wants them, so they grow angry and bitter. They die alone.

Butchness haunted my childhood. When I refused to wear dresses or begged to go the all-boys school instead of the all-girls school, the adults around me caught glimpses of what my future would be, but they didn’t see a happy, handsome butch with a strong queer community around her. They saw the boogeyman coming for me, and they were afraid.

So they slapped down some rules. One: I couldn’t wear my brothers’ clothes. Two: I couldn’t cut my hair. Three: I couldn’t walk to 7-Eleven even though my brothers could at this age, because the rules are different for girls; I was told: Sit up straighter, brush your hair, what are you wearing?, don’t talk so loudly, don’t spread your legs so wide, you could be so pretty if you’d only put on some makeup.

By the time I reached middle school, I second-guessed every gesture, every outfit, every comment I made in class. I studied the other girls at school. I bought the clothes they wore and made myself small to match them—sitting so I took up less space, keeping my voice down, and pinning my arms at my sides so I wouldn’t over-gesture. When I was myself, so many people were disappointed in me. When I was someone else, the only one disappointed was me.

Predictably, this hyper-awareness spiraled into anxiety, which spiraled into suicidal depression and self-harm. I had good friends, good grades, and a reputation for being funny and easy-going. But I knew in my heart that I was wrong. I was a terrible person masquerading as a not-terrible one. I daydreamed constantly about ways to die.

My story is not unusual. 45% of LGBTQ youth and more than 50% of all trans and nonbinary youth have seriously considered attempting suicide in the past year. They are four times more likely than their straight peers to attempt suicide. Experiencing discrimination, violence, or a lack of acceptance at school or at home all increase the risk of a suicide attempt. Having pronouns respected, having an LGBTQ club at school, and having support from family or peers all reduce the risk. So does seeing positive representations of your own identity in media.

The first time I saw a butch character, I was 21 and reading the memoir Fun Home. In the book, Alison Bechdel describes her childhood: throwing tantrums when forced to wear dresses, admiring men’s clothing, deliberately trying to get mistaken for a boy—all experiences I’d had, too.

Before that moment, I assumed those experiences meant something was wrong with me. Now, I started to wonder if my shameful childhood memories might actually be a pattern, adding up to the identity I was slowly starting to embrace. For the first time, I realized I might not be the only person who felt this way.

After that glimpse, I became desperate for more butch representation. I read Stone Butch Blues and Tomboy Survival Guide and watched If These Walls Could Talk 2. Each story showed me a new way to look at myself—with understanding, gentleness, and even pride, instead of hatred or disgust. I started tentatively using the word butch to describe myself. I found the courage to start shopping in the men’s section. Before, mirrors had been a shameful catalog of everything I hated about myself and wanted to change. Now, every time I saw my reflection, I felt a surge of joy.

But I quickly ran through all the butch representation I could find. In part because there still isn’t nearly enough LGBTQ representation out there. But mostly because the vast majority of Sapphic books, movies, and shows overwhelmingly center two conventionally attractive women who could pass for straight. While that is certainly a real and valid pairing, there’s a reason that it’s so often the only type of WLW (“Women loving women”) relationship we’re allowed to see—it’s the least threatening to mainstream social norms.

Whenever I searched for butch media and found nothing new, I felt restless and frustrated. Now that I knew that it was possible to see my own experiences reflected back at me, I was desperate to feel that way again. I still had so many questions. What was I supposed to do when someone accused me of being in the wrong bathroom? Should I hide my butchness when interviewing for jobs or wear it proudly? Could I still like rom-coms and squeal over babies, or did I need to strip that part of myself away to become a “real” butch? Did I need to learn how to ride a motorcycle?

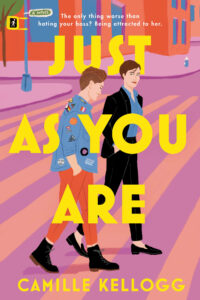

Eventually, that longing became unbearable. So, I decided to stop waiting and write the story that I wanted to read. A story filled with queer characters and experiences, like questioning your gender or feeling insecure about claiming certain labels. A story that showed butch characters, gender non-conforming characters, gender-questioning characters, and trans characters as attractive, desirable, three-dimensional, and fulfilled. Eventually, that story became a book—my first novel, Just as You Are, which was published in April.

Butch representation in stories made me feel less alone. Those few pieces of butch media I could find gave me a way to start liking myself, instead of hating myself. It’s not an exaggeration to say that these stories saved my life. Now, I want to share my own stories, in the hopes that someone, somewhere, might need to hear it.

Camille Kellogg is a queer writer based in New York City, where she works as an editor for children’s and young adult books. She studied English and creative writing at Middlebury College and attended the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference on a fiction scholarship. She’s passionate about queer stories, cute dogs, and bad puns.

Camille Kellogg is a queer writer based in New York City, where she works as an editor for children’s and young adult books. She studied English and creative writing at Middlebury College and attended the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference on a fiction scholarship. She’s passionate about queer stories, cute dogs, and bad puns.

Discussion2 Comments

I remember my girlfriend in the 80s telling me not to put my hands in my pockets because I looked too butch. She eventually left me for a straight relationship, largely because she wanted somebody to support her. But whenever my partner and I would get together with her in Los Angeles, she always wanted to go to a gay bar. Go figure. This was a great story.

Thank you so much for sharing your story! I wish I could have read texts like this one when I was younger and struggling with exactly the same issues (wearing the “wrong” clothes, liking the wrong sports, wrong behavior, wrong way of walking/gesturing, etc.). My mother just couldn’t accept me as a non-girlish girl and had her own struggles trying to “understand” my way. I guess she was just afraid, that my life as a naturally androgynous looking woman would be terrible and lonely. It is not. Although, still, sometimes it is not very comfortable if people stare at you as if your a total alien.. Well, their problem, not mine 😉

Again, thank you for your writing and go on spreading those thoughts of yours!