ONE OF THE PIVOTAL FIGURES in the Gay Liberation Movement, Charley Shively died on Friday, October 6th, at the Cambridge Rehabilitation and Nursing Home, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He had been a resident there since June of 2011, suffering from Alzheimer’s. He would have turned eighty on December 8, 2017.

ONE OF THE PIVOTAL FIGURES in the Gay Liberation Movement, Charley Shively died on Friday, October 6th, at the Cambridge Rehabilitation and Nursing Home, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He had been a resident there since June of 2011, suffering from Alzheimer’s. He would have turned eighty on December 8, 2017.

At the 1977 Boston Gay Pride march, Shively became infamous for burning pages from the Bible—as well as his insurance policy, his Harvard diploma, and a teaching contract—as a protest against oppressive institutions. This act of incendiary and effective political theater—it nearly caused a riot—later obscured his work as an organizer, scholar, poet, and publisher.

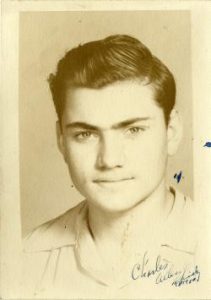

Born in poverty in Gobbler’s Knob, Ohio, in 1937, Shively excelled in high school and entered Harvard College in 1955. After being granted a masters in history at the University of Wisconsin in 1959, he entered the doctoral program in history at Harvard. During this time he worked at Boston State College, where he was active in New University Congress, antiwar working groups in the American Historical Association, and other anti-Vietnam war groups. His graduation from Harvard in June of 1969 coincided with the Stonewall Riots. That summer he began what was to be his life’s work: gay liberation. His vision of gay liberation was deeply and uniquely inflected by his study of, and belief in, anarchism.

After helping form Gay Men’s Liberation in Boston, Shively worked on the first issue of Lavender Vision, a 1970 co-gendered Gay Liberation newspaper. A year later helped form the Fag Rag Collective, which published the first national post-Stonewall gay political journal. In Fag Rag Shively published a series of twelve essays, beginning with “Cocksucking as an Act of Revolution,” that became foundational to post-Stonewall gay male political theorizing. Written in a conversational  tone with a mixture of personal confession, everyday anecdote, Karl Marx, Herbert Marcuse, Mikhail Bakunin, Kate Millett, and Shulamith Firestone, these influential pieces became canonical. During the next decade the ever-changing Fag Rag Collective was held together by Shively’s presence and persistence. He was also responsible for founding Fag Rag Books, the Good Gay Poets collective and Press (which published noted poets such as John Wieners and Ruth Weiss), and Boston Gay Review, a journal of cultural criticism.

tone with a mixture of personal confession, everyday anecdote, Karl Marx, Herbert Marcuse, Mikhail Bakunin, Kate Millett, and Shulamith Firestone, these influential pieces became canonical. During the next decade the ever-changing Fag Rag Collective was held together by Shively’s presence and persistence. He was also responsible for founding Fag Rag Books, the Good Gay Poets collective and Press (which published noted poets such as John Wieners and Ruth Weiss), and Boston Gay Review, a journal of cultural criticism.

Along with his political essays, Shively’s academic work included the six-volume edited Collected Works of Lysander Spooner (1971)—a 19th century social anarchist—and A History of the Conception of Death in America, 1650-1860, his doctoral dissertation (1987). His groundbreaking research on Walt Whitman resulted in two books—Calamus Lovers: Walt Whitman’s Working Class Camerados (1987) and Drum Beats: Walt Whitman’s Civil War Boy Lovers (1989)—which he viewed as an expression of political commitment as well as academic research. A lifelong poet—he first published poems in high school—Shively wrote at least one poem a day. His Nuestra Señora de los Dolores: The San Francisco Experience was published in 1975. He was active in the Boston poetry scene, particularly Stone Soup Poets. Indeed he understood himself primarily as a poet—his poems were spare, imagistic, almost religious—a word he would have rejected—and mystical in their intensity. He leaves three finished poetry manuscripts.

During the 1970s and ’80s, he was involved in numerous LGBT organizations, was a founding member of Gay and Lesbian Advocates and Defenders (GLAD), and, along with Fag Rag, wrote frequently for Gay Community News, Gay Sunshine, The Guide, and poetry journals. Almost always dressed in overalls and speaking in his slow, southern Ohio drawl—an inflection he often used for ironic effect as he made his arguments—he was a ubiquitous figure at political meetings and rallies. During this time, he taught full-time, traveled to Kenya, Ecuador, and Vietnam on three Fulbrights, and was hired as a tenured professor at U-Mass Boston in the American Studies Program.

Shively’s partner beginning in 1964, Gordon Copeland, died in 1994, the year Shively was diagnosed with HIV. He retired from U-Mass in 2001 and began exhibiting signs of Alzheimer’s a few years later. During this time he traveled to Paris to do research on homosexuality and the French Revolution.

Charley Shively’s legacy is in his writings, and also in the example of his insistent refusal—always with humor—to follow the rules, and often not even to acknowledge them.

Michael Bronski is professor of media studies at Harvard University.