There was no moment in Max’s childhood where I thought he might identify as someone other than a woman. He was curious, bold, and often analytical. We called him an old soul for the way he assessed situations with eyes that were almost black and probing, showing compassion and patience, even as an infant. His preschool teacher called him a “kind leader.”

Max taught himself to knit from YouTube videos when he was ten. He produced make-up videos as a tween, but did so with a bit of tongue-in-cheek, poking fun at the pursuit, while being exceptionally good at it at the same time. He was plucked out of school from a scout to attend an elite ballet school, which he hated because of the homogeneity of the kids, who were expected to look and act the same; room for individuality was scarce. Max would make his own clothes at home or wear a “tiny hat” to school when the mood struck him. When the director told me they wouldn’t be keeping Max on past grammar school because he didn’t stretch every day (much to Max’s relief), he added that he wanted to be more like Max when he “grew up” – individualistic and immune to criticism.

Earlier in the year, a school administrator cornered me to discuss Max running in the halls. I braced myself, but she merely leaned in and said, “They’re really fast. They should join the track team.” Max would readily concede he wasn’t what anyone might term a tomboy. A combination of rebel and fashionista, he had a penchant for heels, dresses, and glitter.

My divorce put my kids in a tailspin. They were thirteen – an incredibly vulnerable age. They lost the only home they ever knew, and within five months, I got breast cancer. I felt like I needed to put on a brave face for everyone, but kids know better. Your kids can tell if something’s wrong, and my anxiety pulsed through them on a daily basis for months.

When Max told me one day in eighth grade that his pronouns had changed, that he was nonbinary, I barely blinked. His twin, Sophie, told me that she was gay when she was around ten or eleven, and this didn’t surprise or rattle me in the least. “Are you upset?” she asked. I replied that the only thing that bothered me was that she was speaking with her mouth full.

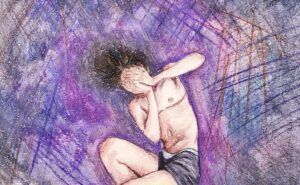

But the day Max told me that he no longer used they/them pronouns, preferring ‘he/him’ instead, and he would be dropping his dead name, I cried. “Do you mean I can no longer say that name?” I asked. “She’s gone, entirely?” Max looked at me through tears and said, “I’m right here.” Of course he was. The very same incredibly beautiful human being he’d always been – right there. And he needed me now more than ever.

For a few months after Max came out, I secretly thought I did something to push him to what I mistakenly assumed was a decision based on trauma. I blamed myself for those hard years following the divorce – for losing their home, for having cancer and being less emotionally available, and for marrying a man who made the kids uneasy (a marriage that lasted less than two years; kids know better). I blamed myself for what I presumed was Max’s need to escape womanhood. I suggested that he thought being a woman was too terrifying a prospect to endure.

Max’s response surprised me; he was angry. “So you’re making this about you,” he said. “You think that my being trans is somehow a bad thing that happened to me for something you did or didn’t do? No, this isn’t about you.” He expressed understanding, however, that he hadn’t always identified as male. But it didn’t make it any less real, he said. “Stop blaming yourself for everything, Mom” my old soul offspring reassured me.

I wasn’t immediately convinced. At an age when gender identity may still be less than ironclad and curiosity is a natural byproduct of sexual and gender awakening, it felt like it was suddenly almost atypical not to adopt new pronouns. I wasn’t sure Max’s gender identity would stick, but I knew that he needed my support.

At his eighth grade graduation, one of Max’s teachers described him as an “activist, leading a generation, giving us hope for the future.” “You are unapologetically true to yourself, and you stand up for what you believe in,” she said to him. “Not too many students would respond to hearing homophobic language by creating a lesson about the LGBTQ community, then attend an all-staff meeting during after-school hours to present it to the entire staff. Yes, Max came to Professional Development to teach us, so that we taught the lesson how Max wanted it to be taught. I might be biased, but I personally think it was the lesson of the year.”

Over the next few years, I accidentally misgendered Max a few times, mostly at family reunions, where old habits die hard. When Max corrected me or our family, I occasionally witnessed a bit of uncertainty or disfavor in a family member’s expression, but I was grateful and deeply comforted by the fact that they cared ultimately about making Max feel loved.

Max chose a name that I told him was on the short list before he was born. We thought of calling him “Maxine” and condensing this to “Max.” We had his name legally changed in high school, and a new social security card made for him in his first year of college.

Suicidality among transgender youth is heart-wrenching. I understand that a parent may think it’s a “phase,” but sometimes it’s not. Regardless, why potentially alienate your child because their identity isn’t what you envisioned?

Max is nineteen now, and scheduled for top surgery this month. He’s undergone extensive counseling, worn a painful binder all day every day for almost four years, and has had testosterone therapy for almost two years. Clearly, this is not a phase. And Max’s proclivity to wear make-up (he’s an artist, so the make-up tends towards unconventional, fantastical paintings rather than Cover Girl photo shoots) and occasionally wear skirts, makes for even less acceptance by strangers since he’s male. He takes it all in patient stride, as he’s always done. Our wise, old soul. Waiting for everyone else to catch up.

Lena Milam is never happier than when she’s outward bound on a lone hike in the woods (she’ll take her children along as often as they’re willing). Her heart belongs to her wonderful 19-year old twins, Max and Sophie Faber. She works as a Program Coordinator at the Division of Medical Ethics at NYU Langone, is a clinical hospice volunteer, and teaches yoga to cancer patients at Hope Lodge, NY.

Lena Milam is never happier than when she’s outward bound on a lone hike in the woods (she’ll take her children along as often as they’re willing). Her heart belongs to her wonderful 19-year old twins, Max and Sophie Faber. She works as a Program Coordinator at the Division of Medical Ethics at NYU Langone, is a clinical hospice volunteer, and teaches yoga to cancer patients at Hope Lodge, NY.