Spring 1955 in Paris. WWII was long past, but times were still tough all over Europe. Nevertheless, the Paris theater, opera, fashion, and art scenes were flourishing.

Bliss Hebert and I, stationed in the U.S. Army in Orléans, were in Paris every weekend attending all of the opera, musical, and theatrical performances that meager Army salaries allowed. The exchange was 350 francs to the dollar, which bought a bistro dinner or a ticket to the opera.

One Sunday matinée at the Theatre de Champs Élysées, Bliss and I attended a marvelous performance that was part of an International Festival of Theater. During intermission, we were strolling the upstairs gallery in our summer uniforms marveling at the framed black and white photographs of famous theatrical stars, premieres, dancers, conductors, and actors of the last fifty years.

A middle-aged, balding Frenchman in a suit greeted us: “Bonjour. These are marvelous photographs, n’est-ce pas?”

“Yes, they are amazing,” we replied, wondering if he was trying to pick us up.

“Are you boys interested in le théatre?”

“Yes, Bliss is a music school graduate and wants to be an opera coach and stage director, and I want to be a set and costume designer,” I replied.

“Parfait!” he exclaimed. “You should meet Romaine de Tertoff. You must know him of course by his theatrical name, Erté. He is the most famous stage designer in Paris, and he knows everyone.”

This did sound like a typical gay come-on, but we agreed that we would love to meet Erté. After exchanging information, we were certain that we would never hear from him again. Actually, neither of us had ever even heard of Erté, so we looked him up in our headquarters’ library. Sure enough, Erté was famous. He had designed film sets in Hollywood, sets and costumes for the Paris opera and French theater, and he had painted magazine covers for Harpers and Vogue.

A couple of weeks later, Bliss and I were driving toward the suburb of Bologne-Sur-Seine to the pristine Deco building where Erté lived. Up we went in a tiny filigreed cage of an ascenseur. The apartment door was opened by a 5’ 4” impeccably groomed, smiling, middle-aged queen. It was Erté, attired in a full-length velvet dressing gown.

“Welcome, welcome,” he cooed.

Inside, the entrance hall walls were covered from floor to ceiling in gray silk draperies. These panels were on hinged folding rods that opened to reveal the walls behind. On the walls and hanging from the metal rods were dozens of amazingly detailed gouache paintings, jewelry designs, castle interiors, stage sets, and costumes all by the magical “one-haired” brush of Romaine de Tertoff. He could design everything!

The next room was smaller. One wall was dominated by a large aquarium filled with exotic fish. Above it was an aviary replete with cooing pigeons. On either side and lining the rest of the walls were bookshelves filled with art books and portfolios filled with historic prints. A bureau stood in front of this wall, with an armchair behind it. There Erté sat, a few tubes of gouache paint and a container of fine watercolor brushes were his only tools.

He was working on the stage set for Berlioz’ Faust for the San Carlo Opera House, the largest stage in the world, yet his sketch was only 5” by 9”. It depicted a proscenium filled with a sort of whatnot shelving with a scene going on in each of its twenty or so horizontal and vertical spaces.

“The scene in the village will be here on this level,” Erté pointed out. “The Walpurgis Night will be here in this space. Did you know that I work all night long, and sleep during the day?”

A dinner invitation followed that first meeting. The most intriguing part of Erté’s apartment was his bar. The floor-to-ceiling bookcase to his right pivoted and swung open on hidden hinges and revealed a complete bar with mirrors, bottles of liquor, and glassware. The pièce-de-résistance was not the spectacular interior, but the plywood backing of the bookcase. Erté had entertained most of France’s arts royalty, and all had autographed this plywood in pencil. Later, Erté arduously painted them over in bright gouache colors. During cocktails, Bliss and I both added our signatures to that pantheon.

Bliss returned to the U.S. and to civilian life. I was due for special “early release,” so I filled out my request to be special counselor at a summer camp in Maine and reported to my commander, who signed off.

I remained in Orléans through the spring. My acceptance to Yale School of Drama finally came. My G.I. Bill of $110 a month was approved, and I was leaving Paris the next morning to begin my new life in theater. Erté and his young lover Claude invited me for a farewell dinner.

After dinner Erté gave me a tour of his bedroom. It was a small room with the walls covered in a beige grass-cloth and a single French daybed with a fitted cover and silk pillows. Claude, as was the closeted gay custom in those days, did not live with Erté.

Erté wanted to show me his new lampshades. They were a pair of conical-shaped parchment shades on pivoting wall sconces. When you turned them on, they revealed meticulous line paintings, by Erté, of muscular French male beauties in every imaginable Kama Sutra position!

“Aren’t they simply divine?” intoned Erté. I have to admit they were extremely arousing.

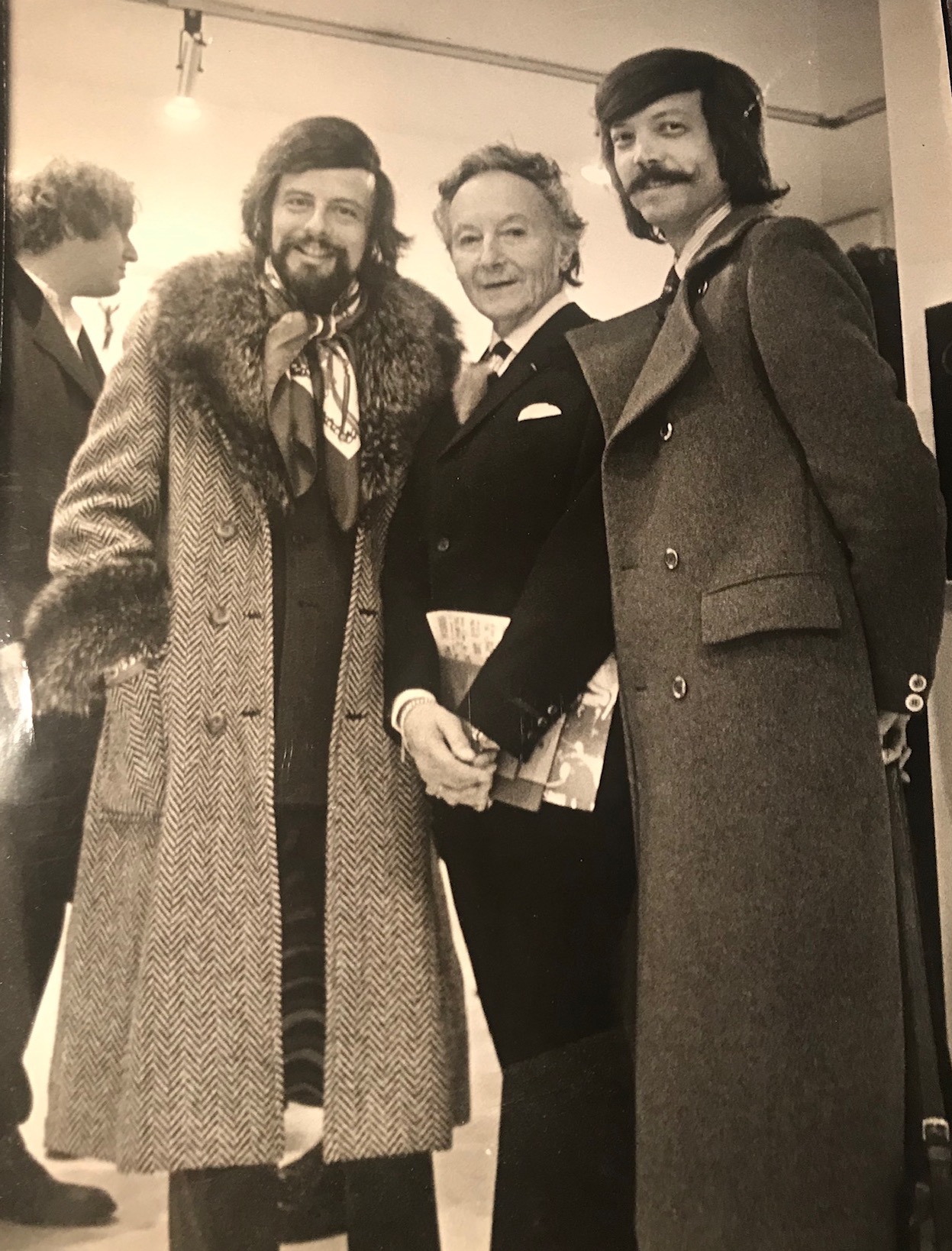

I never saw Claude again, but Erté, Bliss, and I continued to be devoted friends for many years until Erté’s death in 1990.

Gordon Micunis, and his husband Jay Kobrin are well known artists, fashion and theater designers, interior decorators, gourmet chefs and art collectors. You can learn more about them both on Gordon Micunis Designs, Inc.’s website.

Gordon Micunis, and his husband Jay Kobrin are well known artists, fashion and theater designers, interior decorators, gourmet chefs and art collectors. You can learn more about them both on Gordon Micunis Designs, Inc.’s website.

Discussion1 Comment

My partner and I were collectors of Erte’ limited edition serigraphs during the eighties. We were on the gallery’s list when a new serigraph was released to get the lowest number. There is a magical fantasy with Erte’s artworks. Of course fantasies drawn from his theatrical design experience. Such fine steady lines depicting the finest of the female figure in glorious cultoure and jewels. Cheerful with brightly painted colors depict delightful positive impact on the senses.